Christians assert that Jesus is a descendant of King David in order to connect Jesus with the Old Testament prophecies that speak of a future Messianic figure who would establish God’s eternal kingdom. According to these prophecies, the expected Messiah would come from David’s lineage. According to 2 Samuel 7:12-13, God makes the following promise to David:

12 When your days are fulfilled and you lie down with your fathers, I will raise up your offspring after you, who shall come forth from your body, and I will establish his kingdom. 13 He shall build a house for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom for ever. (2 Samuel 7:12-13)

This promise is also reinforced throughout the Old Testament.

5 “Behold, the days are coming, says the Lord, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he shall reign as king and deal wisely, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the land. 6 In his days Judah will be saved, and Israel will dwell securely. And this is the name by which he will be called: ‘The Lord is our righteousness.’ (Jeremiah 23:5-6)

This covenant, often called the Davidic Covenant, set the expectation for a Messianic king from David’s line. For example, Isaiah 11:1, reinforces this lineage:

“A shoot will come up from the stump of Jesse; from his roots a Branch will bear fruit.” (Isaiah 11:1)

Here, “Jesse” refers to David’s father, and the “Branch” symbolizes a new leader from David’s lineage. This example of the Branch from the line of King David is also mentioned in passages such as Zechariah 3:8 and 6:12-13. Therefore, tracing Jesus back to David is crucial for Christians because it affirms Jesus as the rightful Messianic King, fulfilling God’s promise to David and marking Jesus as the anticipated savior who would establish God’s eternal kingdom. But does this claim hold up based on the New Testament?

Jesus Geneology According to the Gospels

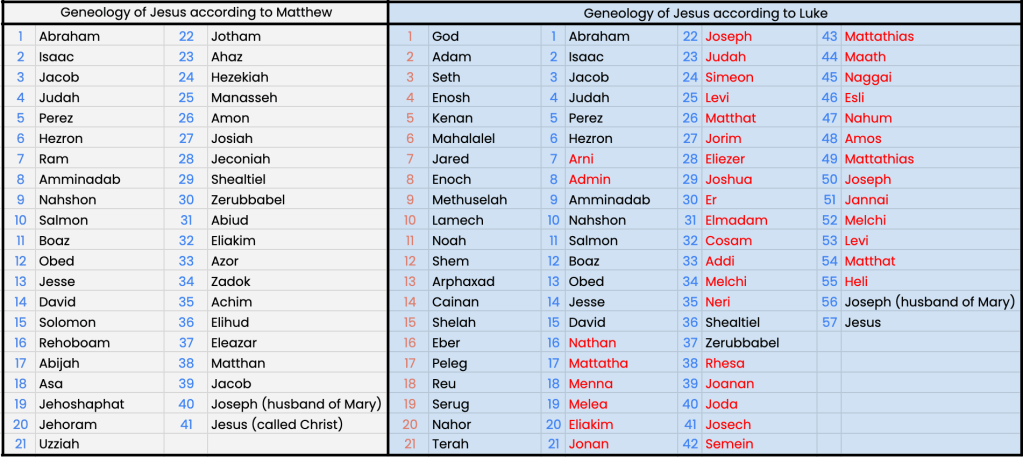

The genealogies of Jesus appear in two of the Synoptic Gospels, Matthew and Luke, but they present notable differences. First, the two accounts differ widely in the number of generations between Abraham and Jesus: Matthew lists 41 generations, while Luke records 57. Moreover, Luke’s genealogy includes 39 names between Abraham and Jesus that do not appear in Matthew’s account. These discrepancies raise questions about the reliability of the genealogical records attributed to Jesus.

However, a more significant complication is that both genealogies trace Jesus’ lineage through Joseph, not Mary. Given that Jesus was said to be born of a virgin with no biological father, he would not have a genetic relationship with Joseph. Therefore, a genealogy from Joseph to David does not provide a meaningful Davidic connection for Jesus. This lack of a biological link through Joseph raises questions about the validity of claiming Jesus as a descendant of David.

Genealogy of Mary

Since we have determined that the genealogies provided in Matthew and Luke do not support the claim that Jesus is a descendant of David, can we find any other indication of Jesus’ genealogy in the gospels?

In the Gospel of Luke, a familial relationship is suggested between Mary, the mother of Jesus, and Elizabeth, the mother of John the Baptist, which also implies a connection between Jesus and John. This relationship is mentioned during the Annunciation when the angel Gabriel appears to Mary to announce the miraculous conception of Jesus. Gabriel tells Mary,

“And behold, your relative Elizabeth in her old age has also conceived a son, and this is the sixth month with her who was called barren” (Luke 1:36).

The term “relative” (from the Greek syngenis) is somewhat broad, indicating a kinship that could mean cousin or a more distant relation. While the exact nature of this relationship is not detailed, the text establishes that Mary and Elizabeth share a family connection, which, by extension, implies a familial link between Jesus and John the Baptist.

In Luke 1:5, we are also given the following details about Elizabeth.

5 In the time of Herod king of Judea there was a priest named Zechariah, who belonged to the priestly division of Abijah; his wife Elizabeth was also a descendant of Aaron.

The passage reveals that Elizabeth was a descendant of Aaron, and her husband Zechariah served as a Jewish priest in the temple. Since Mary and Elizabeth were related, this is the first clue that Mary was also a descendant of Aaron.

Furthermore, in Jewish tradition, only men from the tribe of Levi were eligible to serve as priests, as the Levites were set apart by God for temple duties and spiritual leadership in Israel. Within the tribe of Levi are the descendants of Aaron, Moses’ brother and the first high priest, who were specifically chosen for the priesthood. This Aaronic line was responsible for performing sacrifices, maintaining the temple, and serving as mediators between God and the people.

Zechariah’s role as a priest indicates that he was a descendant of Aaron, giving him the hereditary right to fulfill these sacred duties in the temple. Likewise, Elizabeth’s lineage is traced back to Aaron, meaning John the Baptist was a direct descendant of Israel’s original priestly line on both his mother’s and father’s sides.

Infancy Gospel of James

The Protoevangelium of James, also known as the Infancy Gospel of James, is an early Christian text that provides a narrative of the birth and early life of Mary, the mother of Jesus. This text introduces Mary’s parents, Joachim and Anna, who are portrayed as devout and righteous individuals. They are described as an elderly, childless couple who had been praying fervently for a child.

When Anna was informed by an angel that she was pregnant, she vowed to dedicate her child to the service of the Temple.

Then, behold, an angel of the Lord appeared and said to her, “Anna, Anna, the Lord has heard your prayer. You will conceive a child and give birth, and your offspring will be spoken of throughout the entire world.” Anna replied, “As the Lord God lives, whether my child is a boy or a girl, I will offer it as a gift to the Lord my God, and it will minister to him its entire life.” (Infancy Gospel of James 4)

After her birth and upon turning three years old, Anna and Joachim delivered Mary to the Temple under the supervision of the priest Zechariah, the future father of John.

This dedication of Mary to the Temple again signifies that Mary was a priestly descendant of Aaron and, therefore, not a descendant of David.

Jesus Geneaology & Quran

It is also worth mentioning that the Proto Gospel of James closely parallels the history of the birth of Mary found in the Quran.

[3:33] GOD has chosen Adam, Noah, the family of Abraham, and the family of Amram (as messengers) to the people.

[3:34] They belong in the same progeny. GOD is Hearer, Omniscient.

[3:35] The wife of Amram said, “My Lord, I have dedicated (the baby) in my belly to You, totally, so accept from me. You are Hearer, Omniscient.”

[3:36] When she gave birth to her, she said, “My Lord, I have given birth to a girl”—GOD was fully aware of what she bore—”The male is not the same as the female. I have named her Mary and I invoke Your protection for her and her descendants from the rejected devil.”

[3:37] Her Lord accepted her a gracious acceptance, and brought her up a gracious upbringing, under the guardianship of Zachariah. Whenever Zachariah entered her sanctuary he found provisions with her. He would ask, “Mary, where did you get this from?” She would say, “It is from GOD. GOD provides for whomever He chooses, without limits.”

Also, while the Quran identifies Jesus as the Messiah, it never indicates that Jesus was the Messianic Messiah ben David. Instead, according to the Quran, Jesus’ genealogy is linked to Aaron. For example, it states that when Mary came to her family after the birth of Jesus, they said the following.

[19:27] She came to her family, carrying him. They said, “O Mary, you have committed something that is totally unexpected.

[19:28] “O descendant of Aaron, your father was not a bad man, nor was your mother unchaste.”

(٢٧) فَأَتَتْ بِهِۦ قَوْمَهَا تَحْمِلُهُۥ قَالُوا۟ يَـٰمَرْيَمُ لَقَدْ جِئْتِ شَيْـًٔا فَرِيًّا

(٢٨) يَـٰٓأُخْتَ هَـٰرُونَ مَا كَانَ أَبُوكِ ٱمْرَأَ سَوْءٍ وَمَا كَانَتْ أُمُّكِ بَغِيًّا

David & Aaron Have Different Genealogies

To understand the ancestral lines of David and Aaron and where they originate from, it is helpful to observe their genealogies starting with Abraham. Abraham had a son named Isaac, who fathered Jacob (later called Israel). Jacob had twelve sons, each becoming the ancestor of the twelve tribes of Israel. These sons were Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Dan, Naphtali, Gad, Asher, Issachar, Zebulun, Joseph, and Benjamin.

From the tribe of Levi came the line that led to Aaron:

- Levi → Kohath → Amram → Aaron

Aaron became the first high priest, and his descendants served as priests in Israel, establishing the priestly line within the tribe of Levi.

From the tribe of Judah came the line that led to David:

- Judah … → Boaz → Obed → Jesse → David

David became the king of Israel, founding the royal line known as the Davidic line. This Davidic lineage was associated with the promise of a future Messiah, who would come from David’s line.

This further confirms that Jesus was not a descendant of David and, therefore, was not the Davidic Messiah, as the New Testament claimed.

Jesus Never Claimed to be the Messiah Ben David

While Jesus is associated with messianic expectations throughout the Gospels, he never explicitly claims to be the prophetic “Messiah ben David”—the Davidic king expected to restore Israel’s political sovereignty. Instead, his approach to messianic identity is indirect, often allowing others to interpret his role while emphasizing a spiritual kingdom rather than the political restoration many anticipated. Though people refer to him as the “Son of David” in passages like Mark 10:47-48 and Matthew 21:9, Jesus neither directly affirms nor rejects this title, tacitly allowing the association without overtly endorsing it. In other instances, Jesus acknowledges his messianic role more openly but redefines it in ways that extend beyond traditional expectations.

During his trial, when directly asked if he is the Messiah, Jesus responds with ambiguity. In Mark 14:61-62, he says, “I am,” but quickly shifts to referencing the “Son of Man” coming with divine authority—a title from Daniel 7:13-14 that emphasizes a spiritual, rather than political, kingdom. Similarly, his entry into Jerusalem on a donkey, described in Matthew 21:1-11 and John 12:12-16, is said to fulfill the prophecy of a righteous king from Zechariah 9:9 and is interpreted by the crowd as a messianic act. However, Jesus himself remains silent about any Davidic role during this event.

This “Triumphal Entry” also reveals a notable textual discrepancy. Zechariah 9:9 describes the Messiah arriving “humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey.” Mark 11:1-7, Luke 19:29-35, and John 12:14-15 depict Jesus riding a single young donkey, consistent with Zechariah’s poetic structure. However, Matthew 21:2-7 describes Jesus instructing his disciples to bring both a donkey and a colt, implying that he rode both animals, which some interpret as a misreading of the parallelism in Hebrew poetry. This difference has led scholars to suggest that Matthew interpreted the prophecy literally, assuming two animals instead of one.

This discrepancy, along with other instances where Matthew connects Jesus to prophecies with varying degrees of accuracy, raises questions about his interpretative approach. Matthew’s portrayal frequently emphasizes prophecy fulfillment, sometimes with details that differ from other Gospel accounts, such as those regarding Jesus’ birth and lineage.

In sum, while Jesus allows certain messianic associations, he never explicitly claims the role of the Davidic Messiah and consistently redefines his mission in spiritual, rather than political, terms. This leaves room for a range of interpretations regarding his identity and purpose, challenging the traditional expectations of the Davidic Messiah.

Many Messiahs In the Bible

While most people associate the term Messiah exclusively with the Davidic Messiah, this is not the only messiah mentioned in the Bible or even prophesized to come. In the Bible, the concept of a “messiah” (meaning “anointed one”) appears in various forms, representing different figures chosen by God for specific roles. These messianic figures include kings, priests, and prophets.

David as Messiah

David himself was appointed Messiah by the prophet Samuel and established as Israel’s ideal king.

Then the Lord said, ‘Rise and anoint him; this is the one.’ So Samuel took the horn of oil and anointed him in the presence of his brothers, and from that day on the Spirit of the Lord came powerfully upon David. (1 Samuel 16:12-13)

David was later anointed a second time by the people of Judah after Saul’s death:

Then the men of Judah came to Hebron, and there they anointed David king over the tribe of Judah. (2 Samuel 2:4)

Finally, David was anointed as king over all of Israel, solidifying his role as the chosen leader of God’s people:

When all the elders of Israel had come to King David at Hebron, the king made a covenant with them at Hebron before the Lord, and they anointed David king over Israel. (2 Samuel 5:3)

Solomon as Messiah

Solomon, David’s son, was also anointed as king. His anointing marked him as the successor to David, fulfilling God’s promise that David’s descendants would continue to rule. Solomon’s anointing by the priest Zadok and the prophet Nathan further emphasized the sacred nature of his kingship:

Zadok the priest took the horn of oil from the sacred tent and anointed Solomon. Then they sounded the trumpet, and all the people shouted, ‘Long live King Solomon!’ (1 Kings 1:39)

Another messianic figure is Cyrus the Great, a Persian king who is unexpectedly called “God’s anointed” (Isaiah 45:1), even though he was not an Israelite. Cyrus was chosen by God to release the Israelites from Babylonian exile and allow them to rebuild Jerusalem and the temple. This demonstrates that the concept of a messiah extends beyond Israel and can include foreign leaders whom God uses for His purposes.

This is what the Lord says to Cyrus His anointed,

Whom I have taken by the right hand,

To subdue nations before him

And to undo the weapons belt on the waist of kings;

To open doors before him so that gates will not be shut (Isaiah 45:1)

Messiah Ben Joseph

The concept of Messiah ben Joseph (Messiah, son of Joseph) is a figure found in post-biblical Jewish eschatology, where he appears alongside the more well-known Messiah ben David (Messiah, son of David). While Messiah ben David represents the ultimate, eternal ruler from David’s lineage, who will bring peace and redemption, Messiah ben Joseph is envisioned as a precursor who leads Israel in the battle against its enemies and sacrifices his life in the process. This concept does not appear in the canonical texts of the Hebrew Bible or the New Testament but emerges in Jewish rabbinic literature, mystical writings, and later eschatological thought.

The Talmud introduces Messiah ben Joseph briefly in Sukkah 52a, where he is described as a warrior-messiah whose death will bring about great mourning in Israel. This passage, which refers to the mourning in Zechariah 12:12, interprets the text as mourning for the slain Messiah ben Joseph, a figure expected to die in the climactic battles preceding the final redemption. In various Midrashim, he is portrayed as a leader from the tribe of Ephraim, descended from Joseph, and tasked with confronting Israel’s enemies. Through his efforts, he prepares the way for the victorious arrival of Messiah ben David, who will establish the eternal kingdom promised to Israel.

In later Jewish mystical texts, particularly within Kabbalistic writings, Messiah ben Joseph’s role takes on an even more redemptive aspect. He is seen as a suffering servant whose sacrificial death atones for the sins of Israel, initiating repentance and spiritual purification in anticipation of Messiah ben David’s arrival. Some interpretations connect his suffering to Zechariah 12:10-12, which speaks of mourning for one who has been pierced, seeing in this passage a foreshadowing of the Messiah ben Joseph’s role as a precursor who paves the way for Israel’s ultimate redemption. This dual-messiah expectation underscores a theme of both suffering and triumph in Jewish eschatology, envisioning a preliminary messianic figure who clears the path for the final restoration led by Messiah ben David.

10 “And I will pour out on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem a spirit of compassion and supplication, so that, when they look on him whom they have pierced, they shall mourn for him, as one mourns for an only child, and weep bitterly over him, as one weeps over a first-born. (Zechariah 12:10)

Was Jesus Messiah ben Joseph?

Some interpretations argue that Jesus could have been understood as fulfilling the role of Messiah ben Joseph due to his sacrificial death, humility, and emphasis on spiritual redemption. Proponents argue that the stories of Joseph, son of Jacob, and Jesus share striking similarities, revealing themes of betrayal, suffering, and ultimate redemption that underscore divine providence and forgiveness.

For example, in the genealogy, according to Matthew, it states that Jesus’ father was Joseph and his grandfather was Jacob, marking the first parallel between Jesus and Joseph in the opening chapter of the New Testament.

16 and Jacob the father of Joseph, the husband of Mary, and Mary was the mother of Jesus who is called the Messiah. (Matthew 1:16)

Both Joseph and Jesus are described as beloved sons: Joseph is favored by his father Jacob, as symbolized by the coat of many colors (Genesis 37:3), while Jesus is affirmed as God’s “beloved Son” at his baptism and transfiguration (Matthew 3:17 and Matthew 17:5).

Both also experience rejection by those closest to them. Joseph’s brothers, fueled by jealousy, plot against him and eventually sell him into slavery for twenty pieces of silver (Genesis 37:28), while Jesus is betrayed by Judas for thirty pieces of silver (Matthew 26:14-15). Their paths continue to align as both are falsely accused—Joseph by Potiphar’s wife, leading to his imprisonment (Genesis 39:16-20), and Jesus by false witnesses during his trial before the Jewish authorities and Pilate (Matthew 26:59-61).

One of the most significant parallels is that the suffering of both Joseph and Jesus ultimately serves to bring about the salvation of others. Joseph’s hardships eventually place him in a position of power in Egypt, where he is able to save his family and many others from a devastating famine (Genesis 50:20). Similarly, Jesus’ crucifixion shows that Jesus was willing to be martyred in order to spread the message of spiritual salvation for humanity (John 3:16-17).

Following their suffering, both are exalted: Joseph is elevated to second-in-command in Egypt, just below Pharaoh (Genesis 41:41-43), while Jesus, after his resurrection, is said to sit at the right hand of God (Matthew 28:18).

Both Joseph and Jesus share the experience of being placed between two others in their moments of trial. Joseph was imprisoned with two fellow inmates, the chief cupbearer and the chief baker (Genesis 40:1-3), while Jesus was crucified between two criminals (Matthew 27:38). In both cases, one companion meets a favorable end, while the other does not: the cupbearer is restored, while the baker is executed (Genesis 40:20-22); similarly, one of the criminals on the cross seeks forgiveness and is promised paradise, while the other mocks Jesus (Luke 23:39-43). Also worth mentioning is the connection between Joseph and the cupbearer and the baker, in light of the Gospel’s association of Jesus with bread and wine. These parallels highlight a theme of salvation and judgment in the midst of suffering for both Joseph and Jesus.

Both figures also display profound forgiveness toward those who wronged them. When Joseph finally reunites with his brothers, he forgives them, telling them, “You meant it for evil, but God meant it for good” (Genesis 50:20). Likewise, Jesus, even in the midst of his suffering on the cross, prays for his persecutors, saying, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). This forgiveness reflects a deep compassion and dedication to reconciliation, embodying a spirit of mercy that defines both of their stories.

In addition to their roles as saviors, both Joseph and Jesus provide sustenance to others. Joseph, in his position in Egypt, distributes food during a severe famine, saving countless lives, including those of his own family (Genesis 41:56-57). Jesus, by contrast, offers spiritual sustenance, describing himself as the “bread of life” that provides eternal nourishment to all who believe in him (John 6:35). Both figures embody the idea of provision, meeting the physical or spiritual needs of those around them.

The broader narrative of both lives shows how God’s plan unfolds through their suffering. Joseph acknowledges that his hardships positioned him to save many lives, stating, “God sent me ahead of you to preserve life” (Genesis 45:5). In a similar way, Jesus’ message and martyrdom are seen as the fulfillment of God’s plan for humanity’s redemption.

These parallels between Joseph and Jesus—beloved sons, rejected by their own, betrayed for silver, falsely accused, suffering leading to salvation, exaltation, forgiveness of betrayers, provision of sustenance, and God’s redemptive plan revealed through suffering—emphasize themes of divine providence, forgiveness, and the transformation of suffering into a means of deliverance for others.

However, there are counterarguments to this interpretation. First, traditional Jewish expectations for Messiah ben Joseph focus on a warrior-messiah who would engage in literal battles to protect Israel, an aspect not seen in Jesus’ mission, which was marked by nonviolence and spiritual teachings. Messiah ben Joseph’s role is typically understood as militaristic, involving defense and physical liberation for Israel rather than a purely spiritual mission. Jesus’ death on the cross, while significant to Christian theology, does not correspond to the anticipated military conflict in which Messiah ben Joseph is expected to perish. Moreover, Messiah ben Joseph is traditionally seen as paving the way for the Davidic Messiah who would bring ultimate redemption and establish an earthly kingdom. Jesus’ claim to a spiritual kingdom rather than a physical one deviates from this expectation, leading to arguments that he did not fulfill the role anticipated by Jewish tradition.

Messiah ben Aaron

In addition to royal figures, the Bible also presents a priestly messiah. The priestly messiah represented Israel before God, making sacrifices and guiding the people towards the right path. These were symbolized by figures like Aaron and his descendants, who were anointed for service in the temple.

13 and put upon Aaron the holy garments, and you shall anoint him and consecrate him, that he may serve me as priest. 14 You shall bring his sons also and put coats on them, 15 and anoint them, as you anointed their father, that they may serve me as priests: and their anointing shall admit them to a perpetual priesthood throughout their generations.” (Exodus 40:13-15)

The concept of a Messiah ben Aaron (Messiah, son of Aaron) is also found in certain Jewish sectarian and mystical traditions as a counterpart to the more widely recognized Messiah ben David (Messiah, son of David). While Messiah ben David represents a royal figure who would restore Israel’s political sovereignty, Messiah ben Aaron is envisioned as a priestly messiah, descending from Aaron, the first high priest, to lead Israel in spiritual and ritual renewal. This dual-messiah expectation reflects a comprehensive vision of redemption, in which both political and religious restoration are achieved for Israel.

One of the primary sources for the concept of Messiah ben Aaron is the Dead Sea Scrolls, specifically texts associated with the Essene community, such as the Rule of the Community (1QS) and the Damascus Document (CD). These texts reveal an expectation of two messiahs: a royal Messiah from David’s line and a priestly Messiah from Aaron’s line. According to these writings, Messiah ben Aaron would lead Israel in religious matters, overseeing temple worship, ensuring ritual purity, and guiding the people in spiritual obedience. The dual roles of priestly and kingly messiahs were seen as complementary, with each figure contributing to Israel’s full redemption—one through governance and justice, and the other through worship and sanctity.

Jesus was a Priest, Not a Warrior

In examining the role and mission of Jesus, it becomes clear that he embodied the qualities of a priest far more than those of a warrior or political leader. Traditional Jewish expectations for the Messiah ben David centered on the arrival of a powerful, kingly figure who would lead Israel to political independence, restore the throne of David, and establish a kingdom of peace and justice on earth. This anticipated messianic role was one of a warrior-king, a liberator who would fulfill the hopes of the Jewish people by overcoming foreign rule and re-establishing Israel as a sovereign nation. However, Jesus’ actions, teachings, and overall mission align more closely with the attributes of a priestly figure, emphasizing spiritual redemption, forgiveness, and reconciliation with God rather than political conquest.

Throughout his ministry, Jesus focused on spiritual transformation and the moral teachings of compassion, humility, and mercy. His message was about the kingdom of God as an internal, spiritual reality rather than an earthly, political one.

For instance, in the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus teaches about love, mercy, and humility, emphasizing values like forgiveness, meekness, and purity of heart. For instance, in Matthew 5:9, he blesses “peacemakers,” and in Matthew 5:44, he instructs followers to “love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” These teachings are markedly non-political and emphasize inner transformation, showing a priestly concern for moral and spiritual purity over political or military action.

His teachings consistently direct followers toward inner change, holiness, and relationship with God, reflecting the work of a priest who helps his followers find their way back to God. Moreover, Jesus’ actions underscore his priestly character. In Mark 10:45, he declares that he “came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” This statement highlights his willingness to sacrifice himself in order to guide people back to the correct path, echoing the work of priests who make offerings to atone for the people. Jesus’ martyrdom on the cross is another profound priestly act, showing people a path to redemption and forgiveness rather than a military victory.

In Matthew 21:12-13, Jesus cleanses the temple by driving out the money changers, declaring, “My house shall be called a house of prayer.” This act underscores his concern for the purity of worship, a distinctly priestly concern for holiness and reverence in relation to God. The temple cleansing can be seen as an assertion of his authority over spiritual matters rather than a political act, further supporting his role as a figure focused on spiritual, rather than political, restoration.

In Hebrews 4:14-16, Jesus is described as “a great high priest who has passed through the heavens.” This portrayal of Jesus as a priest is central to understanding his mission as one of spiritual redemption rather than political conquest.

When Jesus was asked regarding paying taxes to Ceasar, his response stated, “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

15 Then the Pharisees went and took counsel how to entangle him in his talk. 16 And they sent their disciples to him, along with the Hero′di-ans, saying, “Teacher, we know that you are true, and teach the way of God truthfully, and care for no man; for you do not regard the position of men. 17 Tell us, then, what you think. Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, or not?” 18 But Jesus, aware of their malice, said, “Why put me to the test, you hypocrites? 19 Show me the money for the tax.” And they brought him a coin. 20 And Jesus said to them, “Whose likeness and inscription is this?” 21 They said, “Caesar’s.” Then he said to them, “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” 22 When they heard it, they marveled; and they left him and went away. Matthew 22:15–22

In Luke 17:20-21, Jesus clarifies that the kingdom of God is not a physical or political entity, but a spiritual reality within individuals: “The kingdom of God is not coming with signs to be observed… for behold, the kingdom of God is within you.” This teaching directly conflicts with the expectation of a political Davidic kingdom, focusing instead on an inner, spiritual kingdom. Jesus’ emphasis on the internal nature of the kingdom aligns with a priestly mission concerned with spiritual renewal rather than national restoration.

By focusing on reconciliation with God, healing, and teaching a path of righteousness, Jesus fulfilled the attributes of a priest rather than a warrior-king. This distinction challenges traditional expectations of the Messiah, presenting a vision of leadership rooted in humility, personal sacrifice, and spiritual guidance rather than political might.

The focus on spiritual redemption over political power suggests that Jesus did not come as the warrior Messiah ben David, expected to restore Israel’s earthly throne. Instead, he fulfilled a different messianic role, one closer to the concept of a priestly Messiah—who clarifies matters for his constituency and bridges the gap between God and humanity.

Conclusion

There is limited evidence in the Bible to support the claim that Jesus was a descendant of David, let alone fulfilled the role of Messiah ben David, as Christians traditionally assert. One of the primary challenges to this claim centers on lineage. According to Jewish prophecy, such as in 2 Samuel 7:12-16 and Jeremiah 23:5, the Messiah was expected to come directly from King David’s biological line to establish an everlasting kingdom. However, Jesus’ genealogy, as presented in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, creates complications. Both genealogies trace his lineage through Joseph, who, according to Christian belief, was not his biological father due to the virgin birth. This raises questions about how Jesus could fulfill the Davidic prophecy without a direct biological connection to David’s line.

Additionally, the Davidic Messiah was anticipated to establish an earthly kingdom, restoring Israel’s independence and ushering in an era of peace and justice. Prophecies in Isaiah 11:1-10 and Ezekiel 37:24-28 describe the Davidic Messiah as a ruler who would bring about lasting peace, gather the exiled people of Israel, and re-establish David’s throne in Jerusalem. Jesus, however, did not fulfill these political and social expectations. His ministry instead focused on spiritual teachings and the promise of a heavenly kingdom, leaving Israel under Roman rule and the Davidic throne unestablished. This divergence from the anticipated political and national restoration challenges the view that Jesus was the Messiah ben David as traditionally prophesied.

In emphasizing spiritual redemption over political liberation, Jesus aligns more closely with the characteristics of a priestly figure, akin to Messiah ben Aaron, rather than with the traditional expectations of Messiah ben David. Not only can an actual genealogy be supported between Jesus and Aaron, but Jesus’ actions and teachings also better align with what one would expect from the descendants of Aaron rather than David.

The prophetic Messiah ben David was expected to be a powerful, kingly leader from David’s line who would restore Israel’s sovereignty and establish a lasting earthly kingdom. This vision reflected the Jewish hope for a national savior who would bring about political stability and independence. However, Jesus’ mission diverged from these expectations, focusing instead on themes of inner transformation, forgiveness, and reconciliation with God through spiritual renewal—all elements more commonly associated with a priestly role.

Throughout his ministry, Jesus often acted as a spiritual guide for humanity, emphasizing moral and divine teachings that center on personal righteousness, humility, and compassion. His teachings reflect these qualities, underscoring purity, humility, and a dedication to God’s will rather than political ambition or military conquest. This focus on spiritual growth and ethical living aligns more with priestly ideals than with the expected role of a warrior-king.

Jesus’ emphasis on obtaining eternal life through redemption reflects the priestly tradition of atonement rather than a kingly mission of conquest. His act of cleansing the temple further underscores this priestly focus, demonstrating his concern for spiritual worship and purity rather than the re-establishment of David’s political throne.

By prioritizing spiritual redemption and moral transformation, Jesus fulfills a role more closely aligned with the expectations of a Messiah ben Aaron—a priestly messiah anticipated to lead Israel in spiritual purity. Certain Jewish eschatological traditions expected Messiah ben Aaron to prepare the people for the Davidic king by purifying and guiding them toward God. Jesus’ emphasis on healing, forgiveness, and heart-centered teachings aligns naturally with this priestly messianic expectation.

In conclusion, Jesus’ genealogy, teachings, and actions consistently reflect a mission focused on spiritual renewal and reconciliation with God rather than political power or national sovereignty. This suggests that, rather than embodying the traditional role of Messiah ben David, Jesus fulfilled a role more akin to that of Messiah ben Aaron, centered on spiritual redemption and preparing humanity for a deeper relationship with God. This understanding better aligns with the correct messianic expectations and sets his mission apart from the anticipated political liberator that seems to have yet to come from David’s lineage.

Related Articles:

Gracias por ampliar mis conocimientos sobre la historia de jesús o yeshua me resolvieron algunas dudas que tenía, no soy partidario de las religiones, pero si un buscador de caminos espirituales y de la verdad,

LikeLike