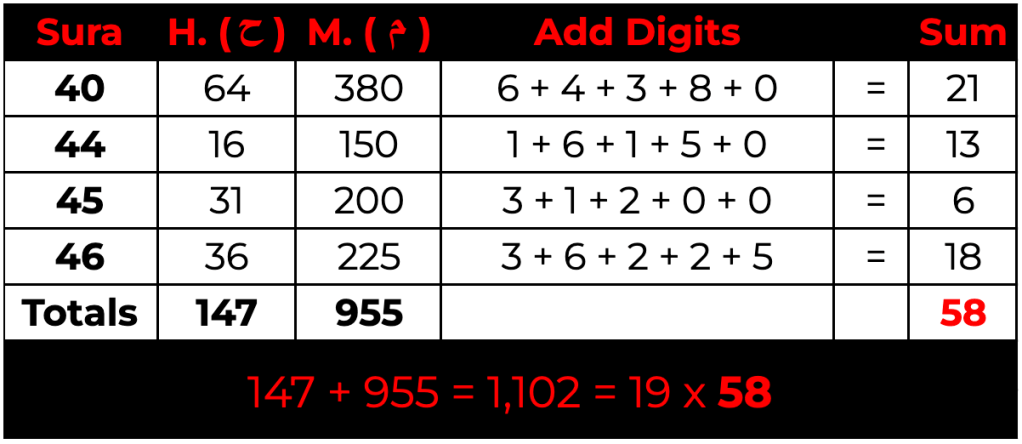

The Quranic initials H.M. ( حم ) prefix seven consecutive suras in the Quran. These are, respectively, suras 40 through 46. If we add all the occurrences of these two letters across all seven of these suras, the total we obtain is 2,147, which is 19 x 113.

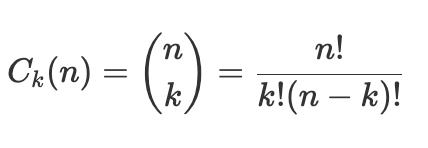

If we check to see if any other sets of these seven suras also provide an aggregate total that is a multiple of 19, we would first need to determine the total number of possible combinations. We can calculate this using the following equation, which shows 127 unique combinations.

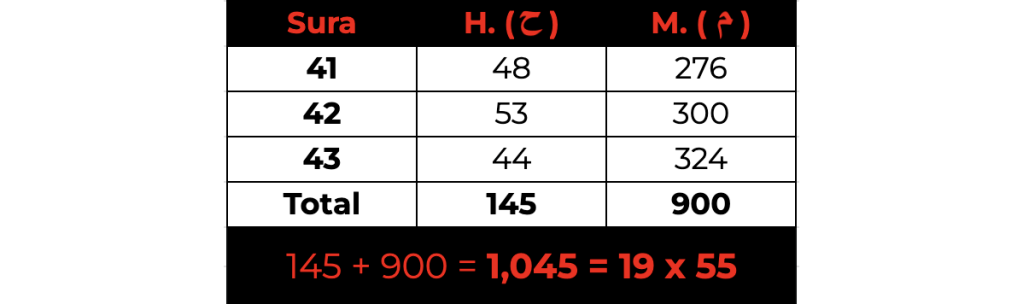

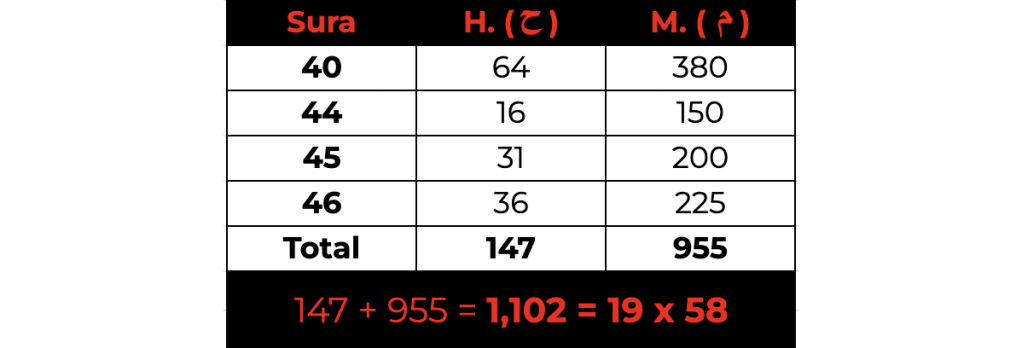

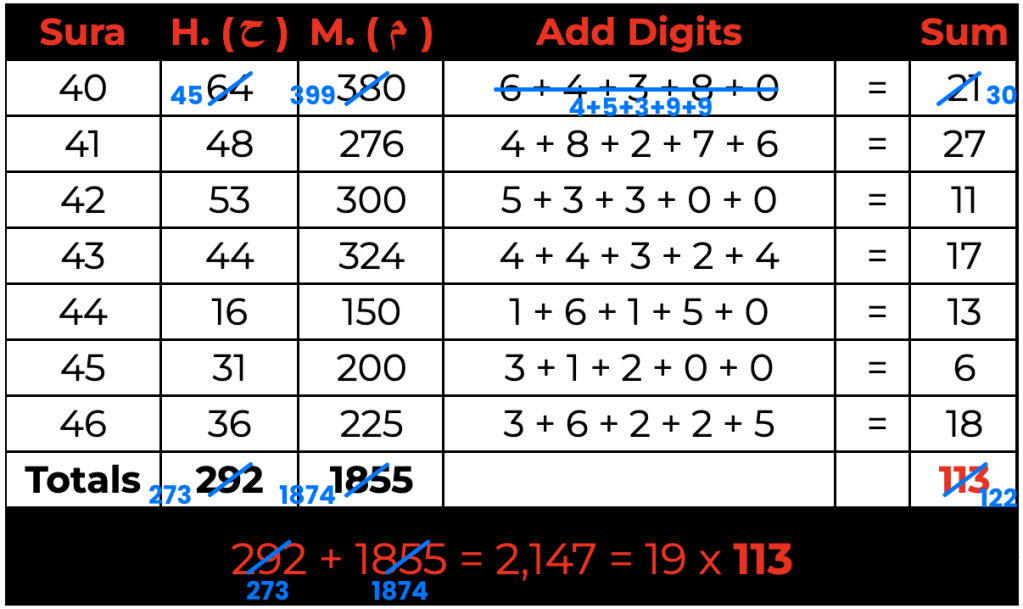

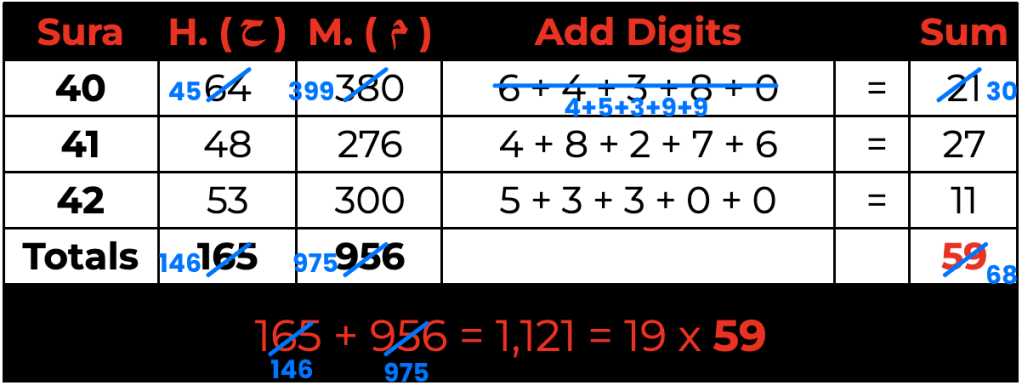

After going through all possible combinations, we see that there are only five sets, including the original set above, that generate a total that is a multiple of 19. These additional sets are the following:

This is not statistically significant as since there are 127 possible combinations, we would expect 127/19, or ~6.68 sets to be a multiple of 19. So, five sets of suras meeting this requirement is well within probability expectations.

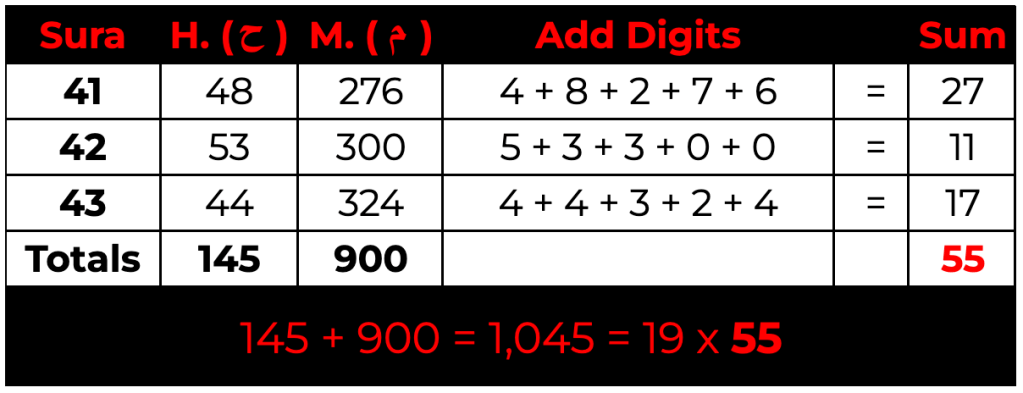

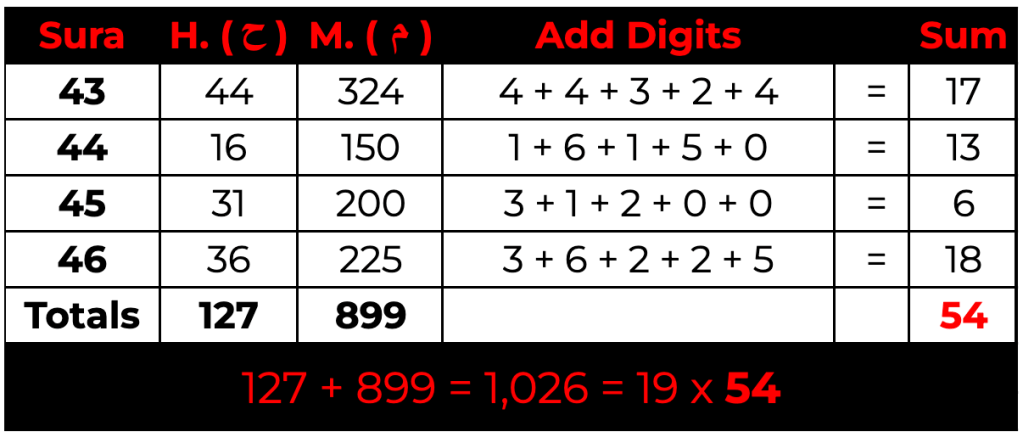

What is peculiar is if we add all the digits of the counts of H. ( ح ) and M. ( م ) in any given sura and then aggregate that total for each of the respective sets, we find that the digits consistently add up to the exact multiplier that makes that entire set a multiple of 19.

No mathematical property dictates that since the set of suras is a multiple of 19, the aggregate total of digits that make up the initial counts for H. ( ح ) and M. ( م ) should equal the multiplier.

For example, if we decreased the occurrence of H. in Sura 40 by 19 while increasing the occurrence of M. by 19 so that the total stayed the same multiple of 19 for the three sets containing this sura, the digits would no longer add up to the multiplier.

Yet, as seen above, we find that the aggregate total of the individual digits in every set forms the exact multiplier that makes that set a multiple of 19. For this to work out in such a beautiful interlocking way for every set, several factors would need to align for such an outcome.

This phenomenon has only two possibilities: it is either a coincidence or done by design.

To figure this out, let’s calculate the probability of such an event happening by chance. To do this, we first need to set our bounds.

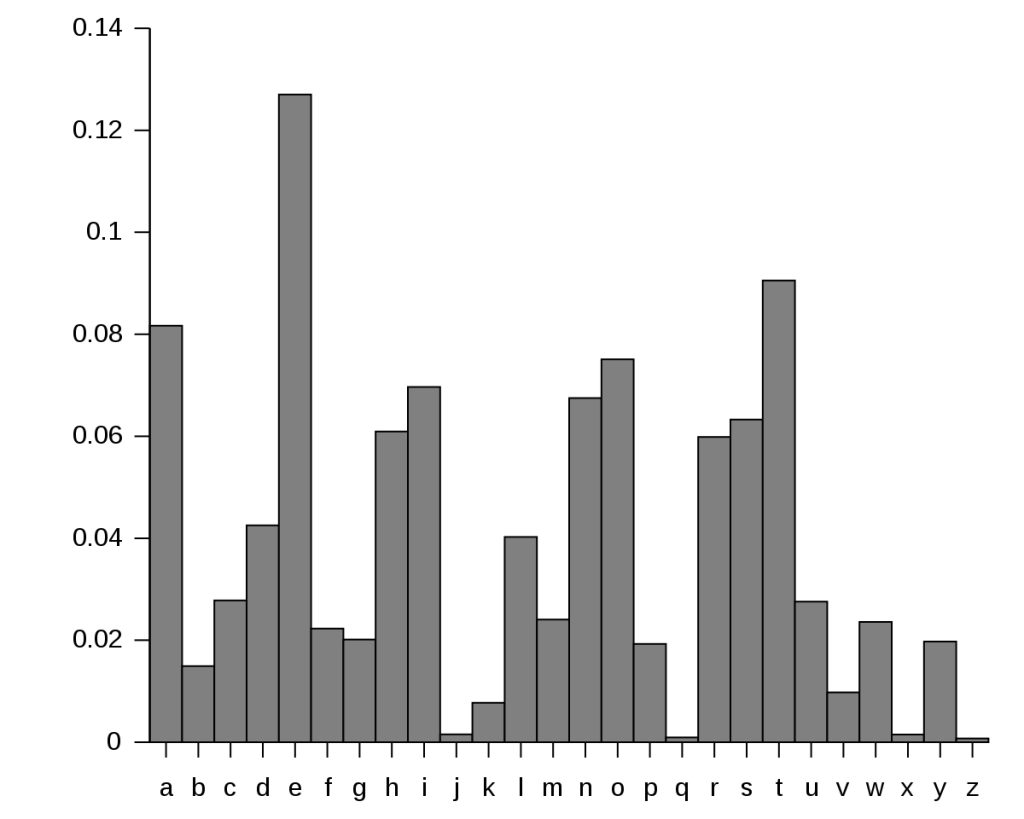

In an unbiased text, there is an expected frequency of any given letter. For instance, the letter “e” is the most common letter in the English language and constitutes roughly ~12% of all letters used in the language. Therefore, if we picked up a regular book and counted the letters, we would expect that roughly 12% of the letters would be the letter “e.”

To apply frequency analysis to the Arabic Quran, we will need to set a baseline of expectations for the frequency of H. ( ح ) and M. ( م ) within the text. To do this, we are going to utilize the H.M. initialed suras and will establish a baseline by comparing the ratio between the frequency that the letters ( ح ) and ( م ) occur in these suras. This can be done by dividing the number of occurrences of H ( ح ) by the number of occurrences of M ( م ) for each of the seven H.M. initialed suras. This will give us the ratio of H/M in the seven H.M. initialed sura, as shown in the table below.

The above table shows that the ratio between ( ح ) and ( م ) initials is as low as 10.67% in sura 44 and as high as 17.67% in sura 42. From this, we can determine that the average ratio between ( ح ) and ( م ) across all seven suras is 15.38%, with a standard deviation of ~2.3%. If we use this as our baseline and expand by three standard deviations from the average, this will provide us the bounds of what a realistic ratio of H. ( ح ) and M. ( م ) can occur in a given text within a 95% probability.

Based on this, I asked ChatGPT to run a Monte Carlo simulation with 1,000,000 trials, where it randomly generated plausible H.M. totals, then checked if the total was a multiple of 19 and, if so, did the digits add up to the multiplier.

After one million trials, zero matches were found. It then increased the number of trials to 10 million, yet it still found zero matches. From this, ChatGPT concluded that the probability this happened by chance, where all five sets that are a multiple of 19 have digits that, when added up, equal the multiplier, is effectively 0%.

Conclusion

This study presents a compelling case that the observed numerical structure in the H.M. ( حم ) initialed suras is not a product of randomness. The alignment of:

- Multiples of 19 in aggregate H.M. counts

- Digit sums aligning with the required multiplier

- Summation of digits matching the precise multiplier across five distinct sets

is statistically impossible to occur naturally. Even with generous assumptions, the analysis shows that the probability of these patterns occurring by chance is virtually zero. Therefore, the most likely cause of this phenomenon is that the author of the Quran did this by design.

However, how could a bedouin in 7th-century Arabia compose such a work? How come no one knew about this for 1400 years? Perhaps he wasn’t lying when he proclaimed:

[40:1] H. M.

(١) حمٓ

[40:2] This revelation of the scripture is from GOD, the Almighty, the Omniscient.

(٢) تَنزِيلُ ٱلْكِتَـٰبِ مِنَ ٱللَّهِ ٱلْعَزِيزِ ٱلْعَلِيمِ

I highly recommend the YouTube video shown at the bottom of this blog. The visual presentation is wonderful.

LikeLike