Below are notes and thoughts from Shady Nasser’s book The Second Canonization of the Qur’an (324/936). This book examines the process of Qur’anic canonization, focusing on how the seven canonical readings of the Qur’an were standardized. This “second canonization” was led by Ibn Mujahid in 936 CE (324 AH), a pivotal figure in Islamic history who established what became the accepted seven modes of Qur’anic recitation.

5 Key Stages in Canonization:

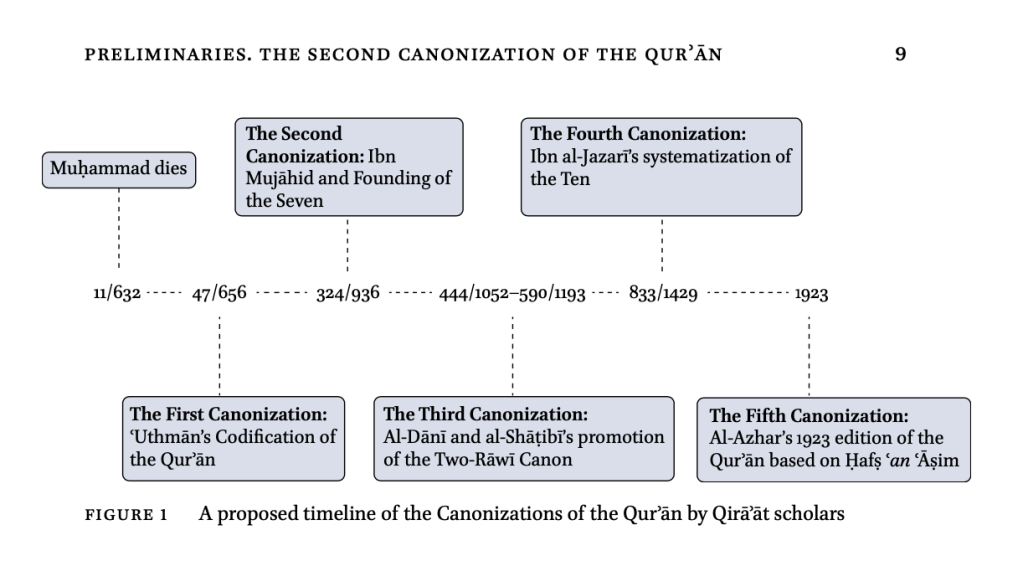

According to Professor Nasser, the five canonizations of the Quran can be seen in the following chart. The history of Qurʾānic canonization involved several key stages. The first canonization occurred between the era of Uthman and the late 3rd/9th century. The second canonization was led by Ibn Mujahid, who selected Seven Eponymous Readings amidst many circulating readings, laying the foundation for the Seven Canonical Readings. The third canonization involved standardizing these Seven Readings further, as discrepancies continued to emerge through students (rāwīs) of the Eponymous Readers. Scholars al-Dānī and al-Shāṭibī refined and promoted a two-rāwī system per Eponymous Reader, eliminating conflicting transmissions. The fourth canonization by Ibn al-Jazarī added three more readings (Abū Ja‘far, Ya‘qūb, and Khalaf), creating a model of Ten Eponymous Readings, which was enforced through his works and fatwās. Finally, the fifth canonization occurred in 1923, when al-Azhar in Egypt printed a standardized Qurʾān adopting the Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim reading. This edition became dominant worldwide, shaping the modern view of the Qurʾān as a static text, with other readings often seen as deviations from this standard.

Thus, I consider the first Canonization process to have taken place in the period between Uthman and the late 3rd/9th century, when Ibn Muj hid emerged. Early grammatical and exegetical works such as those by Sibawayhi (d. 180/796), al-Farra’ (d. 207/822), al-Zajjaj (d. 311/923), and al-Tabari (d. 310/923) contained rich material on the variant readings of the Qur’an accompanied by expansive discussions of their grammatical and hermeneutical value. p. 6

The second Canonization, the subject matter of this book, occurred at the hands of Ibn Mujahid through his selection of the Seven Eponymous Readings. During Ibn Mujahid’s time, a huge corpus of variant readings and System-Readings—at least fifty according to al-Hudhali (d. 465/1072–3)—was circulating amongst Muslims. Ibn Mujahid selected Seven Readings, which became the foundation of the Seven Canonical Readings. p. 6

Nevertheless, limiting the System-Readings to seven did not stop new variant readings from emerging along with discrepancies which were reported on behalf of the Seven Eponymous Readers. Those Readers had several students (rāwīs), and these students did not transmit a single, unified version of the System-Reading they studied. Therefore, another round of standardization was needed to limit the discrepancies documented within one Eponymous Reading. Ibn Mujāhid’s manual and other Qirāʾāt manuals that were written on the subject were further filtered and refined by Abū ʿAmr al-Dānī (d. 444/1053) in his short work, al-Taysīr fī l-qirāʾāt al-sabʿ, a simplified and abridged manual written for students that became the principal source of the Seven Canonical Readings as we know them today. Al-Dānī’s work was given further momentum by al-Shāṭibī (d. 590/1193) after he wrote Ḥirz al-amānī (al-Shāṭibiyya), a versified rendition of al-Dānī’s Taysīr. Al-Shāṭibiyya became the standard manual of Qirāʾāt used and memorized by Muslim scholars up to today. Al-Dānī and al-Shāṭibī’s contribution to the further systematization of Qirāʾāt was crucial, for they standardized and promulgated the system of two Rāwīs, or two Riwāyas, per each Eponymous Reader. Thus, the third Canonization of the Qurʾān at the hands of al-Dānī and al-Shāṭibī promoted the two Rāwī system and eliminated all other conflicting transmissions attributed to the Eponymous Readers through other rāwīs. p. 6-7

The fourth Canonization marked the “official” inclusion of three more Eponymous Readings in the Canon of the Seven at the hands of Ibn al-Jazarī (d. 833/1429). His didactic poem al-Durra al-muḍiyya normalized the three additional Eponymous Readings of Abū Ja‘far, Ya‘qūb, and Khalaf. Ibn al-Jazarī’s addition of these three readings was by no means novel or groundbreaking; they were documented in Qirāʾāt manuals as early as Ibn Mihrān (d. 381/992), and Ibn Mujāhid himself allegedly hesitated over whether to include Ya‘qūb or al-Kisā’ī in his selection. Moreover, it seems that the mashriqī Qirāʾāt scholars (those from the eastern regions of the Islamic world) tended to go beyond the system of the Seven Readings and their two riwāyas, while the maghribī (Andalusian and north African) authors generally maintained the system of Seven Eponymous Readers with two riwāyas. That being said, Ibn al-Jazarī’s rendition of the Ten Readings through his al-Durra al-muḍiyya, and to some extent his al-Nashr fī l-qirāʾāt al-ʿashr, became the standard model of the system of the Ten Eponymous Readings, perhaps due to his adamant efforts to enforce this system through promoting his textbooks and obtaining fatwās that would sanctify the Ten Readings and condemn those who renounce them. Ṭayyibat al-nashr and al-Shāṭibiyya became the main textbooks students and scholars of Qirāʾāt use today. Despite the efforts of several Qirāʾāt scholars after Ibn al-Jazarī to develop other systems of Qirāʾāt, notably al-Dimyāṭī’s (d. 1117/1705) Fourteen Eponymous Readings, the prevalent and dominant discourse of Qirāʾāt as of today is that of al-Shāṭibiyya and al-Durra al-muḍiyya. p. 7-8

Finally, the 1923 printed edition of the Qurʾān in Egypt under the supervision of al-Azhar set new standards for the modern printing and circulation of the Qurʾān, by systematizing the typescript, recitation marks, verse numbering, and, of particular relevance for this study, by adopting the Reading of Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim. Although this Reading started to gain prominence with the advance of the Ottomans, al-Azhar’s adoption of Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim made it the overwhelmingly dominant rendition throughout the Muslim world today. The 1923 Azhar edition marked the fifth Canonization of the Qurʾān. Since its publication and promulgation, this edition had an indelible impact on our perception of the static nature of the Qurʾānic text, particularly in how we (both as scholars and laity) look at the Qurʾān primarily through the lens of the Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim Reading and consequently treat all the other versions and renditions of the Qurʾān as variations and deviations from Ḥafṣ. p. 8

What Caused A Reading to Become Shadhdha p.16

The concept of shādhdha (anomalous readings) in Qirāʾāt history reflects how certain readings, once widely taught and accepted, became marginalized over time. This shift often occurred when readings diverged from the consensus (ijmāʿ) of the Muslim community. Readers who deviated from the accepted communal standard, even if trustworthy, were increasingly sidelined in favor of those adhering to a standardized set of readings.

The system of the Two-Rāwīs (two transmitters per Eponymous Reader) did not exist in Ibn Mujāhid’s era but emerged later with influence from the North African/Andalusian school and was established by scholars like al-Dānī and al-Shāṭibī. Although Ibn Mujāhid included multiple rāwīs for each reader and criticized some transmitters, later traditions distilled the readings to two main transmitters per reader.

The term shawādhdh itself covers both readings that align with the rasm (script) of the muṣḥaf and those that do not; the former are called irregular readings, while the latter are labeled as anomalous. Ultimately, the formation of the Canonical Readings was driven by consensus, even as more reliable or trustworthy readers were known beyond the Canon’s established Seven Readers and Two Rāwīs.

How, when, and why had the very same readings become shādhdha in different periods in the history of the transmission of the Qurʾānic text, despite the fact that these readings were previously recited, taught, and transmitted by the Muslim community? p. 16

I have suggested earlier that the concept of anomaly or shudhūdh in the Qirāʾāt discipline was associated with more than mere divergences from the official consonantal script (rasm) of the muṣḥaf. Shudhūdh was almost always viewed in contradistinction to ijmāʿ. The Qurʾān readers who diverged from the jamāʿa (community) and the consensus, or “a” consensus, were eventually marginalised in favour of those who adhered to the standard reading of the community, or “a” community. p.18

I have argued elsewhere that the concept of the Two-Rāwīs did not exist during Ibn Mujāhid’s time; that this phenomenon began to take shape at the hands of the North African/Andalusian school of Qirāʾāt, particularly with ʿAbd al-Munʿim Ibn Ghalbūn (d. 389/999), the father; and that it was finalized and crystallized at the hands of al-Dānī (d. 444/1052–3) and al-Shāṭibī (d. 590/1194). p.19

[R]āwīs who diverged from the consensus of their peers and fellow transmitters, were gradually excluded from the Canon, such that over time, their readings and transmissions became categorized as shādhdha. Despite the fact that many of these transmitters were reportedly trustworthy and reliable readers of the Qurʾān, whereas some of the Canonical Rāwīs and the Eponymous Readers themselves were considered by many scholars and critics to be weak, untrustworthy, and unreliable Qurʾān readers, the very fact that these Rāwīs and Readers collectively agreed on a corpus of Qurʾānic readings was the main driving force behind forming the Canonical body of Qirāʾāt. p.19-20

He stated that only those who were uninitiated in the science of Qirāʾāt would make such claims, but those who truly understood the discipline were well aware of the fact that there existed more reliable Readers of the Qurʾān than the Seven, as well as more trustworthy and reliable rāwīs than the Canonical Two. p.20

Ibn Mujāhid did transmit and document variants from multiple rāwīs, and he never restricted himself to two Rāwīs per Reader. It is true that he relied more heavily on certain rāwīs than others, and that many of these rāwīs became later on part of the Two-Canonical Rāwīs.18 Nevertheless, Ibn Mujāhid did not hesitate to disagree with and criticize these transmitters, and to resort to other rāwīs for corroboration and authentication. p.20

One should always keep in mind that the Arabic word shawādhdh does not differentiate between variants that agree or disagree with the rasm of the muṣḥaf. Thus, the shawādhdh which agree with the rasm will be called irregular readings, while the shawādhdh which disagree with the rasm will be called anomalous readings. p.20

How Many Transmitters Were There? p.23-24

This table outlines the transmission of Qirāʾāt (Qurʾānic readings) through key figures categorized as Eponymous Readers, Canonical Rāwīs (primary transmitters), and Ṭariq (secondary transmitters) based on Ibn al-Jazarī’s al-Nashr.

- For each Eponymous Reader (main originators of the readings), there were two selected designated Canonical Rāwīs who transmitted their readings. For example, the selected readers of Nāfiʿ’s readings were Qālūn and Warsh.

- Additionally, for each Rāwī, there are two Canonical Ṭariq, who are secondary transmitters responsible for further propagation of the readings. For instance, Qālūn’s readings were transmitted through Ṭuruq like Abū Nashīṭ and Al-Ḥulwānī.

- The “Transmitter from each Ṭuruq” column shows the number of individual transmitters associated with each Ṭuruq.

- The “Total numbers of Transmitters” column provides a final count of all transmitters for each Rāwī, illustrating the relative influence and spread of each reading. For instance, Abū ʿAmr’s reading through Al-Dūrī had 126 transmitters, indicating its wide circulation.

This structure reflects how the Qurʾānic readings were transmitted through multiple layers of authoritative chains, contributing to the stability and continuity of the Qirāʾāt tradition over time.

What is Ḥafṣ ʿan ʿĀṣim? p.25-27

The Canonical Reading of ʿĀṣim was primarily transmitted through two rāwīs, Ḥafṣ and Shuʿba, even though other students of ʿĀṣim also passed down his readings. This means that what is understood as “ʿĀṣim’s Reading” is, in practice, different versions transmitted through these students, with variations emerging among them. Notably, there is no single, unified prototype of the ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ transmission; instead, there are multiple versions, though the differences among them are minor.

To standardize these readings, Qirāʾāt scholars eventually selected certain key transmitters, known as ṭuruq, for each rāwī to create a more consistent canon. For example, ʿAmr b. al-Ṣabbāḥ became a significant ṭarīq (transmission route) of ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ, with his version widely disseminated and documented in sources like Ibn al-Jazarī’s al-Nashr. Other transmissions of Ḥafṣ’s rendition existed, often through single strands of transmission (SST), which sometimes led to shawādhdh (anomalous) readings.

Ibn Mujāhid documented multiple ṭuruq for ʿĀṣim’s Reading, showing at least nine transmission chains, but only ʿAmr b. al-Ṣabbāḥ’s transmission became canonical, while others led to anomalous readings. This pattern of standardization and selection applied not only to ʿĀṣim’s line but also to other Eponymous Readers, like Nāfiʿ and Abū ʿAmr.

The two Canonical Rāwīs of ʿĀṣim were Ḥafṣ and Abū Bakr Shuʿba.28 Despite the fact that several other rāwīs studied and transmitted from ʿĀṣim, these two became our main source for documenting his Eponymous Reading. Thus, what we received in Qirāʾāt manuals were different versions and renditions of ʿĀṣim’s Reading through different transmitters, the most important of whom were these two apprentices, Ḥafṣ and Shuʿba. Consequently, one can speak of the transmission of Ḥafṣ from ʿĀṣim (ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ) and ʿĀṣim → Shuʿba, but one cannot speak of the transmission of ʿĀṣim alone, for his Reading did not exist on its own without the renditions transmitted by his students. If this was true in the case of ʿĀṣim’s transmission, then what about the renditions of both of his Rāwīs? Did we receive a single, unified prototype rendition from Ḥafṣ? The answer is no. Just as ʿĀṣim’s students disagreed amongst one another and transmitted his Reading in different forms and variations, the renditions of both Ḥafṣ and Shuʿba were also transmitted in multiple forms and different variations through several students they had. Consequently, there was no single, unified rendition of ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ, but in actuality there were several versions of ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ, despite the fact that the differences amongst these versions were small and relatively inconsequential. What we today understand as ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ is only one rendition from al-Shāṭibiyya and al-Taysīr, selected from several other renditions, some of which were documented in the sources but others of which were either ignored or lost. As a matter of fact, another round of standardization was carried out to produce a unified rendition by Ḥafṣ and limit the many transmitters from him who disagreed with and contradicted one another. Thus, two transmitters were chosen for Ḥafṣ, and for every Canonical Rāwī of the Eponymus Readings. The Qirāʾāt tradition called these transmitters ṭuruq (sing. ṭarīq). The example of ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ applies to the rest of the Eponymous Readers and their Rāwīs. Accordingly, just as a prototype of ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ did not exist, uniform prototypes of Nāfiʿ → Warsh or Nāfiʿ → Qālūn, Abū ʿAmr b. al-ʿAlāʾ → al-Dūrī, Ḥamza → Khalaf, and so forth, did not exist either. p. 25-26

The diagram below shows the full and partial transmissions of ʿĀṣim’s Reading through Ḥafṣ, as documented by Ibn Mujāhid. The data of this stemma and all subsequent stemmata are scattered throughout Kitāb al-sabʿa. I collected this data from the entire book and consolidated them in these diagrams. p.26

One can see that the rendition of Ḥafṣ reached Ibn Mujāhid through different chains of transmissions (ṭuruq), at least nine, as the diagram shows. As I have argued previously, I believe that the shawādhdh readings were mainly transmitted through SST (Single strands of transmission).31 We can see that out of these nine transmitters only one student of Ḥafṣ was actively teaching and disseminating his rendition, namely ʿAmr b. al-Ṣabbāḥ (d. 221/836). Subsequently, it should not be surprising to find ʿAmr b. al-Ṣabbāḥ becoming a Canonical Ṭarīq of Ḥafṣ, through whom the rendition of ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ reached us. This is confirmed by referring to Table #1 above, which shows ʿAmr b. al-Ṣabbāḥ as a Canonical Ṭarīq of ʿĀṣim → Ḥafṣ with 28 chains of transmission documented in Ibn al-Jazarī’s al-Nashr. The other ṭuruq of Ḥafṣ were single chains of transmission, which, as a matter of fact, gave rise to several shawādhdh readings, such as Ḥafṣ → Ḥusayn al-Juʿfī, Ḥafṣ → Hubayra, Ḥafṣ → Abū ʿUmāra al-Aḥwal, and others. What kind of variant readings did these SST transmit on behalf of Ḥafṣ, and how did Ibn Mujāhid record and respond to their transmissions? p. 26-27

Sixty-Six Problematic Transmissions in Ibn Mujāhid’s Kitāb al-Sabʿa p. 60

Ibn Mujāhid’s efforts to canonize the Seven Eponymous Readings aimed to establish a standardized system by selecting seven main readings and then refining each reading to minimize discrepancies. However, variations continued within each reading due to differing transmissions, reflecting a process of “canonization within canonization.” Evaluating more readings led to even more variations, as multiple reciters introduced new discrepancies. Contrary to a single, static Qurʾānic text, the readings evolved organically through the addition of various renditions and transmissions.

Professor Nasser identified 66 instances where Ibn Mujahid identified problematic transmissions, primarily focused on vocalization variations that had limited impact on meaning. In these instances, he openly disagreed with certain readings by prominent figures like Ibn ʿĀmir and Ḥamza, although later scholars tended to accept these readings without question. Over time, the Qurʾān came to be transmitted through a more limited set of channels, yet the transmission was never fully uniform, with each eponymous Reader’s readings branching into multiple versions through their students (rāwīs and ṭuruq).

Ultimately, the attempt to ensure the tawātur (continuous transmission) of the Qurʾānic text preserved its general structure but failed to prevent minor variations in wording and pronunciation, leading to an array of authentic yet slightly different versions of the text. This chapter highlights the complex process of selecting transmitters in Qirāʾāt, noting that no single, unified system was consistently passed down by the eponymous Readers and their students.

When Ibn Mujāhid embarked upon the project of collecting the Seven Eponymous Readings, he wanted not only to limit the System-Readings to a specific number, which happened to be seven, but also to standardize the renditions of these Seven Readings. The process was that of canonization within canonization. The first step was to create a canon made up of seven systems that were selected from several other existing Eponymous Readings. The next step was to systematize the content of each of these Eponymous Readings, since discrepancies and multiple transmissions for individual variants were common within each System-Reading. Transmitters of the same Eponymous Reading did not agree on all its particulars. The community of the Qurrāʾ tried to emulate the system of isnād authentication developed by the muḥaddithūn. p.60

The relationship between Qirāʾāt and Ḥadīth transmissions will be explored in more depth in Chapter Three, but it is sufficient for now to state that the more transmissions the Qurrāʾ acquired for a System-Reading, the more variants and discrepancies this eponymous Reading showcased. Variant readings did not emerge only as an outcome of different interpretations or intelligent deciphering of the ʿUthmānic consonantal outline (rasm), as Goldziher and Nöldeke, and centuries before them al-Zamakhsharī (d. 538/1143), Ibn ʿAṭiyya (d. 546/1151), and Ibn Khaldūn (d. 808/1406), had suggested; or as a consequence of the deliberate modification of variants in order to accommodate certain local fiqh rulings, as Burton has proposed;224 or as a result of phonetic and syntactical differences amongst various Arabic dialects (lughāt), as the Islamic tradition argues.225 Variant readings also emerged due to transmission errors. Ascribing transmission errors to the seven Eponymous Readers became unfathomable in later Muslim scholarship, since each Reading was in its entirety authenticated beyond doubt (kull wāḥida min al-sabʿa mutawātira). p.61

The following sixty-six examples comprise most of the cases in Kitāb al-Sabʿa where Ibn Mujāhid openly disagreed with the readers regarding the validity and correctness of the variants they transmitted. I documented all the cases where Ibn Mujāhid deemed the variant itself to be erroneous or the transmission of the variant to be faulty. I avoided ambivalent statements in which Ibn Mujāhid’s position was not pronounced. p.63

Further, amongst the sixty-six transmission errors listed below, there are instances where the Eponymous Readers or their Rāwīs were reported to have abandoned certain variant readings and integrated new ones into their System-Reading. p.64

Ibn Mujāhid showed no hesitation about openly disagreeing with an eponymous Reader or Rāwī whose reading did not satisfy the criteria he formulated for a valid Qurʾānic transmission. This contrasts with how Muslim scholars in later periods accepted every individual reading in the system of the seven and ten eponymous Readings without contention. The critical remarks issued by Ibn Mujāhid against Ibn ʿĀmir, Ḥamza, and some canonical Rāwīs such as Qunbul are generally absent in later Qirāʾāt scholarship. Notwithstanding Ibn al-Jazarī’s eight hundred and fourteen (814) unique channels through which the ten eponymous Readings were transmitted and documented, the Qurʾān is recited today through 40 channels (28 channels for the seven Readings): each eponymous Reader has two Rāwīs and each Rāwī has two Ṭarīqs. p.89

On the other hand, one cannot speak of a single, unified, coherent, and systematic rendition of any eponymous Reader. The more transmissions collected by the immediate transmitters, the rāwīs, and the ṭuruq, the more variants the eponymous Readings showcased. By the time that the discipline of Qirāʾāt emulated that of Ḥadīth by applying similar methods of authentication, it was already too late to realize that the outcome was undesirable, for the huge corpus of Qirāʾāt had been already transmitted, recorded, and circulating among Mulsims. What was thought to be a single, unified, and static “Qurʾān” transmitted through tawātur became an organic text whose readings and renditions kept multiplying and “mutating” with every new transmission. Corroborating and authenticating the Qurʾānic text through multiple chains and ṭuruq to prove its tawātur via a multitude of transmitters who could not possibly collude on error and forgery succeeded as far as the general structure and arrangement of the Qurʾān, but failed when it came down to the details of its individual words, let alone the “Arabic” performed aspect of the text. p.91-92

In this chapter, I have established what I believe to be crucial elements concerning the selection process of the transmitters of Qirāʾāt. An eponymous Reader did not transmit and disseminate a single, unified, systematic System-Reading. Regardless of whether it was the Reader’s intention to teach and transmit multiple renditions of his teachings, his students’ inaccuracy in their transmission, the eponymous Reader’s failure to be systematic and meticulous, or a combination of some or all of these, one should be aware of the fact that the students of the eponymous Readers and the students of the canonical Rāwīs did not transmit an identical rendition of the System-Reading they were taught. Instead, they disagreed with one another about details, both minor and major, of that System-Reading. Seven factors were important in determining the inclusion of rāwīs in the canon of the Qirāʾāt: p.92

Qirāʾāt and isnād Criticism p.107-108

Qirāʾāt scholars did not conduct isnād criticism (evaluation of transmission chains) with the same rigor as Ḥadīth scholars, nor did they systematically apply jarḥ (criticism) and taʿdīl (approval) to assess the reliability of rāwīs and Qurʾān readers. A comparison of biographical sources reveals that taʿdīl and tazkiya (verification of reliability) were less methodically applied in Qirāʾāt than in Ḥadīth. This difference is evident from the extensive biographical works on muḥaddithūn (Ḥadīth transmitters) compared to the limited resources on qurrāʾ (Qurʾān readers).

Did Qirāʾāt scholars perform isnād criticism on the chains of transmissions of the Eponymous Readings, and did they carry out a sophisticated and engaged process of jarḥ and taʿdīl with regards to the rāwīs and readers of the Qurʾān? The short answer is no. A survey of ṭabaqāt dictionaries of both disciplines, Ḥadīth and Qirāʾāt, gives us a clear indication that the processes of taʿdīl and tazkiya, of deeming readers to be reliable or not, did not take place as methodically in Qirāʾāt as it did in Ḥadīth. This is evident through the sheer number of biographical compilations we have on the muḥaddithūn as compared to the scanty number of books we have on the qurrāʾ. p.107

How important was the isnād in the transmission of Qirāʾāt, and why didn’t Muslim scholars compile more books in the genre of Qirāʾāt isnād criticism like they did with Ḥadīth? Moreover, to what extent were these books utilized in the process of establishing the authenticity of the transmission of a certain Qirāʾa? Since the established criterion for accepting a Qurʾānic Reading as canonical was its sound isnād (ṣiḥḥat al-sanad)—a Ḥadīth parameter—the next task is to investigate the criteria for accepting a sound Ḥadīth, after which I will inquire into the applicability of these criteria to Qirāʾāt transmission. p.108

ittiṣāl al-sanad: The isnād of the Qirāʾāt p.109-115

Over time, the standard for validating Qirāʾāt shifted from relying on ijmāʿ (consensus) to focusing on a sound chain of transmission (isnād). While the Eponymous Readings of the Qurʾān are often said to be transmitted through tawātur (mass transmission), this concept is debated, as these readings generally trace back to the Prophet through single chains (āḥād), not mass chains, which raises questions about tawātur.

The isnād documentation often starts with the Eponymous Readers rather than connecting directly to the Prophet, leaving gaps in the transmission between these readers and earlier authorities. For instance, while Nāfiʿ claimed to trace his reading to Ubayy b. Kaʿb, details on the intermediaries are incomplete, raising questions about continuity. This issue extends to other readers, such as ʿĀṣim, whose reading connects primarily to ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and Ibn Masʿūd. Ḥamza’s transmission has a complex chain with several intermediaries, and his reading, once controversial, became more accepted after aligning with notable figures. Al-Kisāʾī’s reading was considered a blend of others, notably Ḥamza’s, without requiring a distinct isnād.

Of the Seven Readers, Ibn ʿĀmir’s chain has the least detail, linking directly to ʿUthmān through a single intermediary. This complexity in isnād documentation across different readers underscores the challenges in establishing uniform chains and the role of selective historical legitimization to uphold each reading’s authority.

As mentioned earlier, a shift took place in the way the validity of the Qirāʾāt was determined: ijmāʿ as an element of a sound Qirāʾa was “nominally” dropped and replaced later on by the criterion of a sound chain of transmission. Moreover, it became commonly held that the seven and ten Eponymous Readings of the Qurʾān were transmitted via tawātur. However, this claim was, and still is, problematic, leading some Muslim scholars to rethink this notion of tawātur as far as Qirāʾāt were concerned, and resort instead to the argument that a sound chain of transmission is enough to establish the validity of an Eponymous Reading. Let us now consider what is meant by a sound chain of transmission and how this Ḥadīth parameter may apply to the isnād of the Qirāʾāt. p.109-110

It is commonly believed that the transmission of the Qurʾān/Qirāʾāt can only be validated through oral attestation, where a trustworthy Imām would transmit from another (thiqa ʿan thiqa, imām ʿan imām). The main point of contention in the isnād of the Qirāʾāt is the period before their collection. One can take a leap of faith and trust the thorough, meticulous, and industrious scholarship and documentation carried out by the Qirāʾāt scholars of the late 2nd/8th century. Indeed, the proliferation of isnād and the ample number of transmitters from the generation of the rāwīs (Ḥafṣ, Warsh, Qālūn, etc.) onward to the collectors of the Qirāʾāt (Ibn Mujāhid, Ibn Mihrān, Ibn Ghalbūn, al-Dānī, etc.) instill confidence in us in terms of the meticulousness and academic integrity of these scholars. They were impartial and scrupulous insomuch as to record the slightest changes of sounds, articulation, and even hand gestures and body language. Nevertheless, the problematic aspect of Qirāʾāt transmission lies in two areas: the first is the generations between the Eponymous Readers and their Rāwīs, and the second is the generation between the Prophet and the Eponymous Readers. p.110

While the theory of tawātur necessitates that tawātur must take place in every single generation of the transmitters, the fact remains that all the Eponymous Readings were transmitted via single strands of transmissions (āḥād) between the Prophet and the seven Readers, which rendered the tawātur of these Readings questionable and problematic. The Islamic tradition emphasizes that all the Eponymous Readings were taught and approved by the Prophet; qirāʾa is sunna: no Eponymous Reader exercised ijtihād in deciphering the consonantal outline of the muṣḥaf. Therefore, each Eponymous Reader possessed an isnād that connected him to the Companions, and eventually to the Prophet. But what then was the full isnād of the Eponymous Readings between the Prophet and the Seven Readers? Qirāʾāt manuals were often silent on this point. The documentation of the isnād usually started with the author of the Qirāʾāt manual and ended at the Eponymous Reader. The isnād between the Seven Readers and the Prophet was either assumed or non-existent. This portion of the isnād was often separately augmented from biographical dictionaries and projected onto the documentation of asānīd at the beginning of Qirāʾāt manuals. For example, all the isnād documentation of the Seven Readings in Ibn Mujāhid’s Kitāb al-Sabʿa stops at the Seven Readers. Yet in the section dedicated to their biographies, several didactic accounts are recorded. One man asked another:

– Which Qirāʾa do you read/follow?

– I follow the Reading of Nāfiʿ.

– With whom did Nāfiʿ read/study?

– Nāfiʿ informed us that he read with [ʿAbd al-Raḥmān] al-Aʿraj, who said that he read with Abū Hurayra, who said that he read with Ubayy b. Kaʿb, who said that the Prophet recited the Qurʾān before him, for Jibrīl commanded the Prophet to recite (ʿaraḍa—aʿriḍ) the Qurʾān in front of him [Ubayy]. p.110-111Apparently, Nāfiʿ claimed that he read the Qurʾān with seventy Successors. Al-Musayyabī, one of Nāfiʿ’s close students, named only five of those Successors because he forgot the names of the rest. In describing how he “compiled” (allaftu) and put together his System-Reading, Nāfiʿ stated that when [two] readers agreed on (ijtamaʿā) a variant he adopted it, but when one deviated (shadhdha) from the rest, he abandoned it. It is obvious from this account how Ḥadīth methodology and terminology were employed in this statement. Below is a stemma that shows how Nāfiʿ received his Reading from the Prophet, which seems to have been mainly attributed to Ubayy b. Kaʿb. p.111

Moving to Ibn Kathīr we notice a less sophisticated isnād that connected him to the Prophet. Note that this Reading was also attributed to Ubayy b. Kaʿb. p.111

As for ʿĀṣim, he reportedly studied with Zirr b. Ḥubaysh (d. 81/700–1) and Abū ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Sulamī (d. 74/693–4). Notwithstanding the reports that al-Sulamī studied with Zayd b. Thābit, Ubayy, and ʿUthmān, it was generally presumed that al-Sulamī’s chief master was ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib. Thus, ʿĀṣim’s Reading was commonly attributed to ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and Ibn Masʿūd. p.111

The isnād documentation of the other Kūfan, Ḥamza, was slightly more problematic. First, the narratives stated that Ḥamza was more inclined towards the Reading of Ibn Masʿūd as inherited by al-Aʿmash, with whom Ḥamza reportedly studied. Second, as one notices in the other stemmata, there were two or three generations separating the Eponymous Reader from the Prophet. The isnād of Ḥamza stands out in that regard, since in some of its strands five individuals separated him from the Prophet. Interestingly, it was the Reading that was least accepted amongst the seven, and which several early Muslim authorities even denounced as bidʿa (innovation), which developed the most sophisticated and detailed isnād between Ḥamza and the Prophet, by connecting him to several Companions and thereby bestowing upon the Reading more legitimacy. That being said, the general consensus amongst the Qurrāʾ believed that the Reading of Ḥamza was mainly connected to ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib through Ibn Abī Laylā (d. 148/765–6), and to Ibn Masʿūd through al-Aʿmash. p.111-114

The Reading of the third Kūfan, al-Kisāʾī, did not call for a separate isnād documentation, since it was assumed that his System-Reading was an amalgamation of Ḥamza’s and other Readers, just like the Reading of Khalaf al-ʿĀshir in Ibn al-Jazarī’s system was considered to be an amalgamation of the Readings of Ḥamza and al-Kisāʾī. Al-Kisāʾī was often reported to have asked Ḥamza about his isnād rather than supplying his own. As for the Baṣran Abū ʿAmr b. al-ʿAlāʾ, his Reading was also attributed to Ubayy b. Kaʿb. There is an emphasis through the accounts that AA adopted his Reading from the Ḥijāz, despite studying with several Baṣran masters, most probably to eliminate doubts concerning the development of his unique style of recitation, and to highlight its approval through Ḥijāzī authorities. p.114

Lastly, the Reading of Ibn ʿĀmir has the least detailed isnād documentation, directly connecting him to ʿUthmān through only one person. p.115

The Mythical Ancestry of Qirāʾāt p.115-119

Ibn Mujāhid’s documentation of the isnād (transmission chains) for the Seven Readers did not originally establish a continuous link to the Prophet. Instead, these chains stopped at the Eponymous Readers, who were then associated with Companions in later sources to legitimize their authority. Later scholars, like Ibn Mihrān, developed more complete isnād that linked each reading directly to the Prophet, though some connections, such as Ibn Kathīr’s to Ubayy b. Kaʿb, remained indirect.

This retroactive attribution of isnād aimed to eliminate doubts about the authenticity of the readings by connecting them to well-regarded Companions. For instance, multiple readings (Nāfiʿ, Ibn Kathīr, and Abū ʿAmr) were tied to Ubayy b. Kaʿb, who was also linked to the ḥadīth of the “seven aḥruf” (modes), which supported the existence of multiple legitimate recitations. Similarly, other readings were linked to figures like ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and Ibn Masʿūd, especially for the Kūfan readings of ʿĀṣim, Ḥamza, and al-Kisāʾī, while Ibn ʿĀmir’s reading was tied to ʿUthmān, aligning with Damascus’s Umayyad legacy.

This practice of attributing readings to prominent Companions helped solidify their legitimacy and avoided any perception that they were derived from individual reasoning (ijtihād). It created a “mythical ancestry” for the readings, enhancing their status and aligning each with revered historical figures, even if variations in the recitations remain puzzling given the shared origins attributed to figures like Ubayy b. Kaʿb.

An intriguing question arises when multiple readers, like Nāfiʿ, Abū ʿAmr, and others, claim lineage back to the same Companion, such as Ubayy b. Kaʿb, yet their recitations vary. This inconsistency suggests that these readings were not simply preserved intact from an original source. Rather, the differences could be attributed to variations in transmission, interpretative practices, or even regional influences.

It is important to note that the above chains of transmissions were presented by Ibn Mujāhid in his introduction to the biographies of the seven Readers, and not as part of the complete chain of transmission between him and the Prophet. In other words, the process of isnād documentation was not utilized at the generation of the seven Readers, which roughly corresponds to the first quarter of the 2nd/8th century. According to written records, the Eponymous Readers were “later” asked by their students how they learned their Qirāʾa, and with whom they studied. Naturally, later Qirāʾāt manuals developed more sophisticated isnāds, where complete and continuous chains of transmission were introduced as full-fledged isnāds that connected the Qurrāʾ community directly to the Prophet. Ibn Mihrān, in his eighty-page documentation of the chains of transmission of the ten Readings, connected each one of them directly to the Prophet through a continuous uninterrupted isnād, unlike Ibn Mujāhid whose isnād documentation stopped at the Eponymous Readers, after which he listed possible connections between each Reader and the Prophet. Nevertheless, while documenting the isnād of the Reading of Ibn Kathīr, Ibn Mihrān stopped at Ubayy b. Kaʿb without directly connecting him to the Prophet. Then, he adduced a statement by Qunbul on behalf of his teacher al-Qawwās al-Nabbāl saying: “We are certain that Ubayy received his recitation directly from the Prophet”. In another instance, Ibn Mihrān introduced a statement by Ibn Dhakwān concerning the master with whom Ibn ʿĀmir studied: “Ibn ʿĀmir read the Qurʾān with a certain man, and that man read the Qurʾān with ʿUthmān b. ʿAffān (wa-qaraʾa ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿĀmir ʿalā rajul, wa-qaraʾa l-rajul ʿalā ʿUthmān)”. Ibn Mihrān added a statement attributed to al-Akhfash al-Dimashqī (d. 292/904): “Ibn Dhakwān did not name the man with whom Ibn ʿĀmir studied, but Hishām b. ʿAmmār determined his identity to be al-Mughīra b. Abī Shihāb al-Makhzūmī”. p.115-116

This particular case of Ibn ʿĀmir is very important in terms of understanding how isnād might have been retroactively projected onto a Qirāʾa in order to legitimize it by connecting it to the Companions and eventually to the Prophet, for the Eponymous Readings were not believed to be the product of fallible human reasoning but rather a sound and direct transmission from the Prophet down to the later generation of the Qurrāʾ. p.116

Another intriguing aspect of the aforementioned asānīd was the attribution of the Eponymous Readings to what I am calling a mythical ancestry represented by Companions who were known “historically” to have been closely associated with the Qurʾān. First, by associating the Eponymous Readings with the Companions, the controversy stemming from the exercise of reason and ijtihād in Qurʾānic recitation was eliminated. Ḥadīth scholarship, especially through uṣūl al-fiqh, and as early as al-Shāfiʿī,46 had already established that all the Companions were ʿudūl.47 Thus, posing the Companions as the originators and main source of all the Eponymous Readings, naturally through the instruction of the Prophet, eliminated all doubts concerning the validity and sanctity of the Qurʾānic Readings. While the choice behind some of these Companions seems logical, it is nevertheless puzzling. Ubayy b. Kaʿb became the principal originator of three out of the seven Readings: those of Nāfiʿ, Ibn Kathīr, and Abū ʿAmr b. al-ʿAlāʾ. Fortuitously, it was also Ubayy to whom a Ḥadīth on the Sabʿat aḥruf was attributed, wherein he expressed his doubts about the Prophet acknowledging different readings of the same verse. p.118

Abū l-Ḥusayn Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj (d. 261/875) and Muḥyī l-Dīn al-Nawawī (d. 676/1277), Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim bi-sharḥ al-Nawawī (al-Minhāj sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim b. al-Ḥajjāj), 18 vols. (Cairo: al-Maṭbaʿa al-miṣriyya bi-l-Azhar, 1929), 6:101–2; Aḥmad Ibn Ḥanbal (d. 241/855), Musnad al-Imām Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal, ed. Shuʿayb al-Arnāʾūṭ and ʿĀdil Murshid, 50 vols. (Beirut: Dār al-risāla, 1995), 35:16–18; cf. Nasser, Transmission, 20. – Footnote #48 p. 118

Be that as it may, Ubayy b. Kaʿb was seen as the originator of the Ḥijāzī school, while ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib and Ibn Masʿūd were taken to be the principal originators of the Kūfan Readings of ʿĀṣim, Ḥamza, and eventually al-Kisāʾī. As for the Reading of Ibn ʿĀmir, the Damascene, who could have been a more fitting choice as the mythical founder of this Reading than ʿUthmān b. ʿAffān, an Umayyad from Quraysh, the father of the codified maṣāḥif and a Companion of Umayyad ancestry, whose alleged Reading and rendition of the Qurʾān became the commonly recited Qirāʾā of the people of Damascus under the Umayyad Caliphate throughout the 1st/7th century? p.119

Tawātur Does Not Require an Isnad p. 122

It is important to take note of the dichotomy between tawātur and isnād, and how Muslim scholarship oscillated between the two terms to authorize the transmission of the System-Readings. While the two terms are not necessarily mutually exclusive, tawātur does not require any kind of isnād criticism in which the identity and background of the transmitters would be scrupulously investigated. In other words, when the conditions of a sound isnād were difficult to realize, tawātur stepped in to fill the gap and cover for the shortcomings of isnād criticism. p. 122

Ṭabarī Attributed Variant Readings to Geographical Communities p.124-128

Al-Ṭabarī generally attributed variant Qurʾānic readings to regional Qurrāʾ communities rather than specific individuals, especially when he disagreed with a reading. Likely aware of the weak isnād documentation for these readings, he refrained from integrating them authoritatively in his Qurʾānic commentary. Unlike in Ḥadīth studies, where fabricated isnāds sometimes linked traditions to more Companions, Qirāʾāt scholars did not attempt to bolster weakly documented readings by associating them with additional early figures.

Al-Ṭabarī almost always attributed the variant readings to the Qurrāʾ communities each in their respective geographical area. When he disagreed with a reading that was known to have been attributed to a certain individual, he would use phrases such as baʿḍ al-qaraʾa or baʿḍuhum, trying as much as possible to avoid the attribution of variant readings to particular individuals. p. 124

Having authored a Qirāʾāt manual on twenty-five Eponymous Readings of the Qurʾān, al-Ṭabarī might have realized the weak isnād documentation of the System-Readings and, subsequently, avoided integrating them into his authoritative commentary on the Qurʾān. Since, for example, he dismissed the possibility of Ibn ʿĀmir being connected to ʿUthmān, how could he have presented this Reading as authoritative when it lacked any isnād that might have linked it to individuals beyond Ibn ʿĀmir himself? p.125

Even if we assume that the isnād was fabricated at that level to connect the Readings to their mythical originators, there seems to be no isnād proliferation to further connect the Eponymous Readers to more Companions. In other words, Qirāʾāt scholars did not try to attribute the poorly documented Readings to more Companions and Successors, as occurred in Ḥadīth, where new isnāds emerged that linked certain traditions to the Prophet via more Companions and Successors. p.128

Differences in Qirāʾāt Are Not Just Grammatical Disputes p.128

Al-Kirmānī (d. circa. 535/1140), for example, gave more than ten different possibilities for reading bi‿smi in the basmala, e.g. bi‿sumu, bi‿suma, bu‿sumu, bu‿smu, bi‿sumu, and others, all of which were considered to be grammatically sound and correct, but which had no basis within the discipline of Qirāʾāt. p.128

5 Applying jarḥ and taʿdīl in Qirāʾāt p.131-136

When Qirāʾāt scholars began treating Qurʾānic recitation similarly to Ḥadīth, the number of variants grew significantly as they used Ḥadīth methods like corroboration. However, applying jarḥ (criticism) and taʿdīl (validation) to Qurʾān transmitters revealed that many respected readers had deficiencies in proficiency (ḍabṭ) and integrity (ʿadāla). Shīʿī scholar al-Khūʾī cited these weaknesses to challenge the credibility and tawātur of the Canonical Readings, although medieval scholars had already noted and defended against such critiques.

As mentioned earlier, when Qirāʾāt began treating the recitation of the Qurʾān as if it were similar to Ḥadīth in content, the number of variants increased exponentially by way of simulating the Ḥadīth model to allow for corroboration (mutābaʿāt and shawāhid). This was true with regards to the matn, i.e. the System-Reading itself. What happened when Muslim scholars tried to apply the criteria of jarḥ and taʿdīl to the transmitters of the Qurʾān? How did the Qurrāʾ feature in the biographical dictionaries in terms of their ḍabṭ (academic proficiency) and ʿadāla (moral integrity)? Surprisingly, many illustrious readers did not fare well, in both criteria. In his attempt to systematically undermine the value of the Canonical Readings of the Qurʾān, the Shīʿī scholar al-Khūʾī (d. 1413/1992) gathered an abundance of data on the Canonical Readers from Sunnī biographical dictionaries. He concluded that the weakness and untrustworthiness of these Readers cast doubts on the credibility of the Canonical Readings, and subsequently their tawātur. Al-Khūʾī was not the first to criticize the Qurrāʾ through their ʿadāla. Medieval Muslim scholars had already paid attention to this problem and devised a counterargument in defense of the Qurrāʾ. First, I will summarize and list the negative information only ( jarḥ, qadḥ) about the seven Readers and their Rāwīs documented in biographical dictionaries. p.131

1) Ibn ʿĀmir: He claimed to be from Ḥimyar, but his true genealogy was questionable (yughmaz fī nasabihi). There existed nine different statements concerning his isnād up to the Prophet. Some people/someone claimed that it was not known with whom he studied the Qurʾān. p.131

1-a) Hishām b. ʿAmmār: When he got older he became senile (taghayyara) and started to read/recite anything that was given to him. He would repeat and transmit anything people told him [with- out inquiring about its truth], but he was more trustworthy when he was younger. Hishām transmitted 400 baseless ḥadīths (laysa lahā aṣl) all with [apparently] good isnāds. A man by the name of Faḍlak [Faḍlak al-Rāzī] used to give these ḥadīths to Hishām, who did not hesitate to transmit them; [in doing so] he almost created a rupture in Islām. Hishām was dictating ḥadīth one day when he was asked: “Who gave you this ḥadīth? He answered: ‘One of my teachers (baʿḍ mashāyikhinā)’”. When he was asked again, he yawned/closed his eyes from sleepiness (fa-naʿasa). Muḥammad b. Muslim al-Rāzī said: “I decided to stop narrating the ḥadīths of Hishām because he used to sell ḥadīth/get paid for teaching ḥadīth”. Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal said: “Hishām was fickle and frivolous”. One day, he was sitting in public while his private parts were visible. A man told him: “Cover yourself”! Hishām responded: “Have you seen it [i.e., my penis]? God willing your eyes will never suffer from ramad (ophthalmia)”. Ibn Ḥanbal purportedly said: “One must repeat the prayer if it was led by Hishām”. p.131-132

1-b) ʿAbd Allāh b. Dhakwān: There were no derogatory comments recorded about him, except that his father was the brother of Abū Luʾluʾa, the assassin of ʿUmar b. al-Khaṭṭāb. p.132

2) Ibn Kathīr: Confusion was recorded in his isnād as to whether he studied the Qurʾān with ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Sāʾib al-Makhzūmī or Mujāhid [b. Jabr]. p.132

2-a) al-Bazzī: Abū Ḥātim said that al-Bazzī’s ḥadīth was weak and that he would never accept it. Al-ʿUqaylī stated that his ḥadīth was munkar. p.132

2-b) Qunbul: He became chief of the Police (shurṭa) in Makka but grew corrupt (kharubat sīratuhu). He lived long and became senile. He stopped teaching the Qurʾān seven years before his death. Ibn al-Munādī narrated that he performed pilgrimage together with Ibn Mujāhid and Ibn Shanabūdh. When they met Qunbul in Makka he was mentally unstable. Ibn Mujāhid started a Qurʾān audition with him, but Qunbul was making so many mistakes in his recitation that Ibn Mujāhid was forced to leave the session. p.132

3) ʿĀṣim: Ibn Saʿd said that he made many mistakes in his ḥadīth. He was not good at memorization, to the extent that Ibn ʿUlayya said: “Anyone whose name was ʿĀṣim had bad memory”. According to Ibn Khirāsh, ʿĀṣim trans- mitted munkar traditions in his ḥadīth, whereas al-ʿUqaylī said: “There was nothing wrong with him except his bad memory”. Al-Dāraquṭnī stated that something was wrong with ʿĀṣim’s memory, and Ḥammad b. Salama said that he became senile before he died. p.132

3-a) Ḥafṣ: Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal said that his ḥadīth was not to be transmitted. Ibn Maʿīn stated he was not trustworthy, while al-Madīnī said that his ḥadīth was weak and should be abandoned. Al-Bukhārī said that the Ḥadīth transmitters abandoned Ḥafṣ’s ḥadīth (tarakūhu), and al-Nasāʾī confirmed that his ḥadīth must neither be learned nor written down. Other critics said that all his ḥadīths were manākīr and bawāṭīl (false, invalid). Not only was he untrustworthy in ḥadīth, but it was reported that Shuʿba (ʿĀṣim’s second Rāwī) was more reliable than him in Qurʾān. Shuʿba complained once that Ḥafṣ took a book/notebook from him and never returned it, and that he used to take people’s books and copy them (an allusion to the criticism that Ḥafṣ used to take knowledge from books and claim it as his own). Some reported that Ḥafṣ was a better reciter than Shuʿba, but that he was a liar (kadhdhāb). Ibn Ḥibbān said that he used to forge and fabricate isnāds. ʿAbd al-Raḥmān b. Mahdī stated that it was not permissible to transmit ḥadīth from him (mā taḥill al-riwāya ʿanhu). p.132-133

3-b) Abū Bakr Shuʿba: there were nine different statements about his real name. Consequently, he was listed under bāb al-kunā: man kun- yatuhu Abū Bakr (those known as Abū Bakr) in Ibn Ḥajar’s Tahdhīb. Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal said that he was trustworthy, but that he made mistakes. Shuʿba used to boast and say: “I am one half of Islam” (anā niṣf al-Islām), in reference to his excellence in Qurʾānic recitation. Yaḥyā l-Qaṭṭān and Ibn al-Madīnī did not think highly of him, especially because he became senile and his memory deteriorated. He often made mistakes in ḥadīth, and his memory was not reliable when he delivered ḥadīth. Abū Nuʿaym stated that amongst his teachers, Abū Bakr Shuʿba was the most likely to make mistakes. p.133

4) Abū ʿAmr b. al-ʿAlāʾ: There were almost no derogatory statements about Abū ʿAmr except the uncertainty surrounding his real name and his boasting that he had never met anyone who was more knowledgeable than himself. Abū Khaythama said that he could be trusted but he did not memorize much ḥadīth. p.133

4-a) Al-Dūrī: Statements about him were generally positive, except for al-Dāraquṭnī, who stated that he was weak, without further specification. p.133

4-b) Al-Sūsī: Statements about him were also positive, except for Maslama b. Qāsim, who deemed him to be weak without proof (bi-lā mustanad). p.134

5) Ḥamza: al-Sājī said that he was trustworthy, but his memorization was bad, and that he was not meticulous in transmitting ḥadīth. Some Ḥadīth scholars criticized his Reading and prohibited praying behind him, but Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal resented it without prohibiting such prayer. Abū Bakr Shuʿba said that the Reading of Ḥamza was considered to be bidʿa (innovation) amongst the community of the Qurrāʾ. Ibn Durayd stated: “I wish that Kūfa would be purified from the Reading of Ḥamza”. p.134

5-a) Khalaf: Ibn Ḥanbal was asked about Khalaf and his consumption of alcohol. He answered that he was aware of this allegation but Khalaf was still a trustworthy, honorable individual. Khalaf allegedly said: “I repeated 40 years of prayers during which I had consumed alcohol according to the legal school of the Kūfans”. Yaḥyā b. Maʿīn said that Khalaf had no clue what Ḥadīth was. p.134

5-b) Khallād: No negative statements were mentioned about him, and he did not feature in the major Ḥadīth biographical dictionaries I have consulted. p.134

6) Nāfiʿ: Aḥmad b. Ḥanbal said that one could learn the Qurʾān from Nāfiʿ but not Ḥadīth. In another statement Aḥmad said that his ḥadīth was munkar. p.134

6-a) Qālūn: He was trustworthy in Qirāʾa, but not very much in Ḥadīth. Aḥmad b. Ṣāliḥ was asked about Qālūn’s trustworthiness in ḥadīth; he laughed and said: “Do you write down ḥadīth from anyone? Qālūn was deaf, but he was able to read people’s lips and correct their mistakes”. p.134

6-b) Warsh: He did not feature in Ḥadīth biographical dictionaries and there were no negative statements about him. p.134

7) Al-Kisāʾī: Ibn al-Aʿrābī praised al-Kisāʾī’s knowledge and said: He was the most knowledgeable of people, despite being a liar/impudent (rahaq). He used to consume alcohol and accompany young beautiful boys, yet he was a great Qurʾān reciter. It was related that one day he led some people in prayers and recited using Ḥamza’s System of recitation. After he finished the prayer, the people in the mosque beat him up with their fists and shoes. When asked why, he replied that it was because of the decadent/lowly Reading of Ḥamza (Qirāʾat Ḥamza al-radīʾa). p.134-135

7-a) Abū l-Ḥārith al-Layth b. Khālid: No negative statements were mentioned about him. p.135

7-b) al-Dūrī: Mentioned above in 4-a). p.135

Rāwīs & Moral Integrity p.135-136

Several Eponymous Readers and Rāwīs faced criticism for lacking moral integrity. Muslim scholars often applied different standards of ʿadāla (moral integrity) to Qurʾān and Ḥadīth transmitters, as trustworthiness could vary between disciplines. However, issues like lying, corruption, and fabricating isnāds undermine credibility across fields. For instance, Ḥafṣ, whose Qurʾānic reading is now the most widely accepted, was listed by Ibn al-Jawzī as a known liar and fabricator in Ḥadīth. Such critiques have raised questions about the reliability of these canonical figures, though some scholars caution against accepting these accusations without thorough investigation.

However, it is worth noting that several Eponymous Readers and Rāwīs did not hold a secure position when it came to their moral integrity. We may agree with how Muslim scholarship tried to separate Qurʾān from Ḥadīth in terms of the criteria of their transmitters’ ʿadāla. One could be trustworthy in Ḥadīth but weak in Qirāʾāt and vice versa. Specialization necessitated applying different standards of scrupulousness to each discipline. Nonetheless, how can we accept that the moral integrity and character of the individual were judged according to different standards based on the discipline? The aforementioned descriptions of lying, corruption, selling ḥadīth, consuming alcohol, and fabricating isnāds are at the core of a transmitter’s moral integrity, be it in Ḥadīth, Qurʾān, or court testimony. Take the case of Ḥafṣ, for example, whose rendition of the Qurʾān is the most widely accepted Qirāʾā today in most Muslim countries. In addition to the statements mentioned about him earlier, Ibn al-Jawzī listed him in his al-Ḍuʿafāʾ wa-l-matrūkīn, describing him as kadhdhāb (liar) who fabricated ḥadīth (yaḍaʿ al-ḥadīth). Appalled by these statements, the editor notes the following in a footnote: “being accused of lying must be thoroughly investigated, but God forbid, he [Ḥafṣ] would not do such a thing”. p.135-136

Anecdote Of Quran Preservation from al-Qurṭubī

Moreover, the Qurʾān was held to be protected from corruption and falsification by the oral tradition, contrary to the scriptures of Jews and Christians. Under the commentary of (Q. 15:9) “innā naḥnu nazzalnā ‿dh-dhikra wa-innā lahu la-ḥāfiẓūna” (Lo! We, even We, reveal the Reminder, and lo! We verily are its Guardian), al-Qurṭubī mentioned the following anecdote: a well-spoken, eloquent Jewish man entered the court of al-Maʾmūn (r. 198–218/813–833), who was impressed by his demeanor and diction. Al-Maʾmūn asked him to convert to Islam, but the man refused. After a year, the Jew paid another visit to al-Maʾmūn, but as a Muslim this time. When asked about the reason for his conversion, he said: “I wanted to put the different religions to the test. I made copies of the Torah, the Bible, and the Qurʾān, but I added and omitted words and phrases. The Jews and Christians bought my copies without noticing the changes I introduced. On the other hand, the Muslims recognized them [in the Qurʾān] and refused to buy my copies. I then realized that the Qurʾān was a preserved and protected scripture. Thus, I converted to Islam”. p.140

The Case of Ibn Shanabūdh (d. 328/939)

Professor Nasser cites the incident between Ibn Mujāhid and Ibn Shanabūdh as highlighting a pivotal conflict in early Qirāʾāt tradition. Ibn Shanabūdh supported the use of shawādhdh (anomalous) readings associated with figures like Ibn Masʿūd and Ubayy b. Kaʿb, claiming sound transmission chains to legitimize them. However, Ibn Mujāhid had him tried, flogged, and forced to repent, insisting on strict adherence to the ʿUthmānic codex, which was seen as authoritative over oral variations.

Despite Ibn Shanabūdh’s respected status as a meticulous and pious scholar and his supposedly sound transmission, his severe punishment raises questions about the treatment of trusted individuals. This incident underscores the early scholarly consensus on the ʿUthmānic rasm as the definitive written standard for Qurʾānic recitation, indicating that fidelity to the written text was prioritized over other reputable oral transmissions. The lesson here is the enduring precedence of the ʿUthmānic text, establishing the principle that adherence to a standardized text, rather than alternative readings, defines orthodoxy in Qurʾānic recitation.

The incident between Ibn Mujāhid and Ibn Shanabūdh has been frequently discussed in scholarship, making it unnecessary to go into it in much detail. In short, Ibn Shanabūdh advocated for the liturgical use of the shawādhdh readings attributed to Ibn Masʿūd and Ubayy b. Kaʿb. He recited these anomalous readings in public and argued that he was in possession of sound chains of transmission, which would readily give these readings legitimacy. Nevertheless, Ibn Mujāhid brought him to trial, after which he was flogged, forced to repent, and pledged that thereafter he would adhere to the rasm of the ʿUthmānic codex.12 The first observation to be made about this incident is the importance of adhering to the written ʿUthmānic recension, which obviously superseded the sound oral transmission for which Ibn Shanabūdh and other Qurʾān readers argued. This does not come as a surprise, for the consensus to adhere to the ʿUthmānic rasm was established very early on. p.141-142

The second observation I want to make concerns the ʿadāla of Ibn Shanabūdh. Scholars held him in high regard as a Qurʾān reader. Al-Dhahabī described him as trustworthy and meticulous in his scholarship (itqānihi wa- ʿadālatihi). He was thiqa, pious, righteous, and possessed immense knowledge in the discipline of Qirāʾāt (mutabaḥḥir). That being said, the trial and humiliation to which Ibn Shanabūdh was subjected, and his denunciation by the Qurrāʾ community, contradicted how a ʿadl, trustworthy individual should have been treated. Ibn Shanabūdh was allegedly stripped naked, flogged, put in a “breaking wheel” (i.e., a Catherine wheel), tortured, and ostracized from Baghdād; all this took place under the nose of his colleagues, the Qurrāʾ. p.142

Human Elements in the Transmission of the Qurʾānic Recitations

The Qurʾān was largely transmitted with certainty, with most variations tied to specific readers or regional traditions. Although tawātur implies a flawlessly preserved oral transmission, Qirāʾāt literature reveals notable disagreements and discrepancies among readers and transmitters. This suggests that the early period of Qirāʾāt involved significant interpretation and adaptation, with readers occasionally forgetting, erring, or adjusting their readings, underscoring the human element in the transmission process.

The vast majority of the Qurʾān was agreed upon and transmitted with certainty. Even the variant readings themselves were, to a large extent, associated with certain Eponymous Readers or Canonical Rāwīs or even regional schools of recitation. The theory of tawātur, or the verbatim oral transmission of the Qurʾān from master to student, assumed an intact, absolutely verified text that was known down to its smallest detail by the professional circle of the Qurrāʾ, let alone the larger Muslim community. Nonetheless, Qirāʾāt literature tells us another story. The disagreements amongst the rāwīs and the discrepancies in the transmission of the “performed” text of the Qurʾān on the level of the Eponymous Readers, their Rāwīs, and their Ṭuruq, suggest that the formative period of Qirāʾāt literature was a time of robust deciphering of the text of the Qurʾān, its meaning, and its performance. Readers of the Qurʾān were human beings and not mechanical audio recorders; they forgot, hesitated, made mistakes, and modified their system-Reading(s) accordingly. p.172

Once Vowels Introduced, Variants Stopped

The important question to be asked is the following: had Arabic and the Qurʾānic text been fully standardized and systematized in the 7th century, would vowels and diacritics be needed to read the text consistently without variations? In other words, why did variants stop emerging after the 4th/10th century? Were we to give the contemporary text of the Qurʾān, stripped of vowels and diacritics, to a trained, professional Qurʾān reciter, would he be as confused as the early Muslim reciters and read ملك (mlk) as malīki or mallāki or milki or malki, or would there be no doubt in his mind that it is either maliki or māliki? p.183

Familiar Notions and Proper Nouns p.187-189

Some variants raise the question of the standardization of the Arabic language and the Qurʾānic text, rather than the extent of dialectical variations and the impact of the script’s deficiency. While it might be acceptable to argue that variations in articulation and vocalization occurred due to differences in the Arabic dialects, it would be difficult to accept that the same process happened in variations of proper nouns and common notions, especially those whose pronunciation was systematized later on in the Islamic tradition. I believe that the most important word in this regard would be ‘Qurʾān’ itself. All Readers articulated the hamza of Qurʾān except Ibn Kathīr, the Meccan, who read Qurān. Was this a dialectal variation of the word “Qurʾān” that we can assume only existed in the time the Prophet? Should one not assume that the word itself was well-known amongst Muslims, that there was no need to introduce a particular pronunciation just to conform to a Reader’s own style of recitation? Even the Readers who were notorious for softening the hamza, such as Abū ʿAmr, always articulated the hamza of the Qurʾān. Was “Qurān” the actual reading of the Prophet and the Meccans to whom the Qurʾān was first revealed? Similar proper nouns and common notions raise the same question. Most Arabs and Muslims are familiar with the name of Gabriel as Jibrīl or Jibrāʾīl, which were also the forms in which the name generally appears in Islamic sources. However, the name has many more variants, all of which are “canonical”: Jabrīl, Jabraʾīl, and Jabraʾil. It seems that mispronouncing the name of Gabriel, a quintessential figure in Islam, was controversial and unsettling enough that a dream was attributed to Ibn Kathīr in which he allegedly saw the Prophet reciting wa-Jibrīla, contrary to the Ibn Kathīr’s standard reading, transmitted as wa-Jabrīla. The variant readings of these important names and common notions are intriguing. They invite us to investigate the significance of these variations, particularly when, how, and in what context they permeated the Islamic tradition. Were Muslims in the 1st/7th century well-educated in terms of the terminology of the Qurʾān, its concepts, and the Islamic narrative itself, including its essential concepts and key figures? The following examples indicate the opposite:

- (Q. 2:62) and (Q. 5:69) wa-ṣ-ṣābiʾīna and wa-ṣ-ṣābiʾūna (the Sabaeans). All the Readers articulated the hamza except N, who read wa-ṣ-ṣābīna and wa-ṣ-ṣābūna.

- Similar to Jibrīl in (Q. 2:98), three different pronunciations were recorded for Michael: Mīkāl, Mīkāʾīl, and Mīkāʾil.

- Throughout (Q. 2, al-baqara), Ibn ʿĀmir read Ibrāhām, while the rest of the Readers read Ibrāhīm

- Nabī (Prophet): none of the Readers articulated the hamza of nabī and its variant forms (al-nabiyyīn, al-nubuwwa, al-anbiyāʾ) except Nāfiʿ who read nabīʾ, al-nabīʾīn, al–nubūʾa, al-anbiʾāʾ, etc., as in (Q. 2:61), (Q. 3:79), (Q. 3:113), and (Q. 3:68).

- Zakariyyā (Zechariah): a hamza was articulated in some variants, reading either Zakariyyāʾu or Zakariyyāʾa in (Q. 3:37).

- Abrogation: the “abrogation verse” (Q. 2:106) reads mā nansakh min āyatin aw nunsihā (And for whatever verse We abrogate or cast into oblivion). IK and AA read nansaʾhā (to delay) instead of nunsihā, which stirred an exegetical debate about abrogation and whether God would make the Prophet forget previously revealed verses or merely delay their revelation.

- The Mysterious Letters: despite the general agreement to recite these letters as disjoint from one another, a considerable amount of variation was reported on behalf of each Reader. In particular, refer to the ten different combinations of (Q. 19:1) k-h-ʿ-y-ṣ.

- (Q. 4:163) All Readers read Zabūr (Psalms), except H, who read Zubūr.

- Elisha: all Readers read al-Yasaʿ, as in (Q. 6:86) wa-l-Yasaʿa, except H and K, who read his name as al-Laysaʿ: wa-l-Laysaʿa

- Diptotes: some nouns had not been properly categorized as diptotes yet, and thus some Readers treated them as such, while other Readers vocalized them as regular triptotes. Examples include (Q. 9:30) ʿUzayrun vs. ʿUzayru, (Q. 11:68) Thamūda vs. Thamūdan, and (Q. 27:15) Sabaʾa, Sabaʾin, and Sabaʾ.

- Al-nasīʾ (The month postponed/Postponing): a pre-Islamic practice which continued shortly after Islam until year 9 after the hijra. The word was pronounced differently by the Readers (nasīʾ, nasʾ, nasiyy, and nasy), perhaps indicating unfamiliarity with both the concept and the term itself.

- Gog and Magog: all Readers read (Q. 18:94) Yājūj and Mājūj without articulating the hamza, except ʿĀṣim, who read Yaʾjūj and Maʾjūj.36

- Sinai: It was read either Sīnāʾ or Saynāʾ in (Q. 23:20).

- Elias: It was read with and without the articulation of hamza; all Readers read (Q. 37:123) wa-inna Ilyāsa, except IA, who read wa-inna ‿l-Yāsa.38 Similarly, another variation appears a few verses later in (Q. 37:130), where N and IA read salāmun ʿalā āli Yāsīna (Peace be upon the followers of Elias) whereas the rest of the Readers read salāmun ʿalā il Yāsīna (Peace be upon Elias).

- The name of the pre-Islamic idol Manāt was read Manāʾata by Ibn Kathīr in (Q. 53:20). Similarly, Wadd was read as Wudd in (Q. 71:23) by Nāfiʿ only; A → Shuʿba → Burayd → Abū l-Rabīʿ also read Wudd, but Ibn Mujāhid deemed the transmission to be wrong.

- The last example would be (Q. 111:1) Abī Lahab, the name of the Prophet’s uncle, where it was read Abī Lahb only by the Meccan Ibn Kathīr.

Interesting article..but it seems to ignore the role of Abu Bakr (RA). Abu Bakr’s compilation was primarily driven by the fear that parts of the Qur’an might be lost due to the deaths of many who had memorized it during the Battle of Yamamah. This concern arose because the Qur’an had not yet been collected into a single volume, existing instead in various fragments and memories.

While both compilations aimed at preserving the Qur’an, Abu Bakr’s effort was more about gathering what existed at that time, whereas Uthman’s was focused on standardizing and unifying recitation practices across the Muslim community.

LikeLike

Peace – this narrative of Abu Bakr’s compilation, the fear of losing the Quran because of the death of many quari after the Battle of Yamama, and collecting the fragments of the Quran has numerous issues with it. Most notably that we are informed in the Quran that the Quran was written and collected into a Kitab during the life of the prophet.

LikeLike