Sunni Muslims often argue that the Hadith is necessary for understanding the context of the Quranic verses. Within the classical Islamic sciences, this genre is known as asbab al-nuzul — literally “the occasions of revelation” or “the causes of descent.” Its intended purpose is to document the specific historical circumstances, events, and questions that allegedly prompted the revelation of particular Quranic verses or passages. Scholars of tafsir (Quranic exegesis) have long treated this genre as indispensable: knowing why a verse was revealed was thought to illuminate its meaning, delimit its scope of application, and ground its interpretation in the lived experience of the earliest Muslim community.

The two most prominent works dedicated specifically to asbab al-nuzul are the Kitab Asbab al-Nuzul of ‘Ali ibn Ahmad al-Wahidi (d. 468 AH / 1075 CE) and the Lubab al-Nuqul fi Asbab al-Nuzul of Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti (d. 911 AH / 1505 CE). Al-Wahidi’s work holds the distinction of being the earliest extant dedicated compilation in the genre and served as the template upon which all subsequent works were modeled; al-Suyuti’s, completed more than four centuries later, expanded upon it with additional narrated material and editorial refinements. That these are the defining works of a genre held to be essential for understanding the Quran immediately raises a question that the tradition has difficulty answering: if knowledge of the occasions of revelation is genuinely indispensable to correct interpretation, why did it take over four and a half centuries after the Prophet’s death for the first person to attempt to systematically compile this? The hadith collections of Bukhari and Muslim were compiled in the third century AH; the earliest sustained theological and legal discussions of the Quran predate al-Wahidi by generations. Yet the genre that supposedly makes the Quran intelligible waited until the eleventh century CE to produce its first dedicated text. The delayed emergence of the literature is itself a signal worth attending to.

Equally telling is the coverage these works actually provide. Al-Wahidi’s compilation addresses approximately 570 verses out of the Quran’s 6,234—less than ten percent of the total. Al-Suyuti’s expanded version covers just over 800 verses, reaching perhaps thirteen percent. If asbab al-nuzul were genuinely required to understand the Quran, the overwhelming majority of the text — upwards of ninety percent of it—would be, by the tradition’s own logic, without recoverable interpretive context. The tradition has never resolved this tension satisfactorily, typically retreating to the position that most verses are sufficiently clear without a specific occasion of revelation, which is to say that the claim of indispensability is quietly abandoned for the very portion of the text the literature cannot cover.

Further, a review of the asbab al-nuzul literature reveals that it is riddled with contradictory narratives. This is often attributed to the fact that the majority of the narrations used are not considered sound; therefore, the expectation that a consistent narrative would be provided is reduced. But what if we limit the analysis exclusively to reports classified as sahih — do the asbab al-nuzul narratives cohere with one another? And if they do not, what does that incoherence reveal about the nature of these reports and their relationship to the Quranic text they purport to explain?

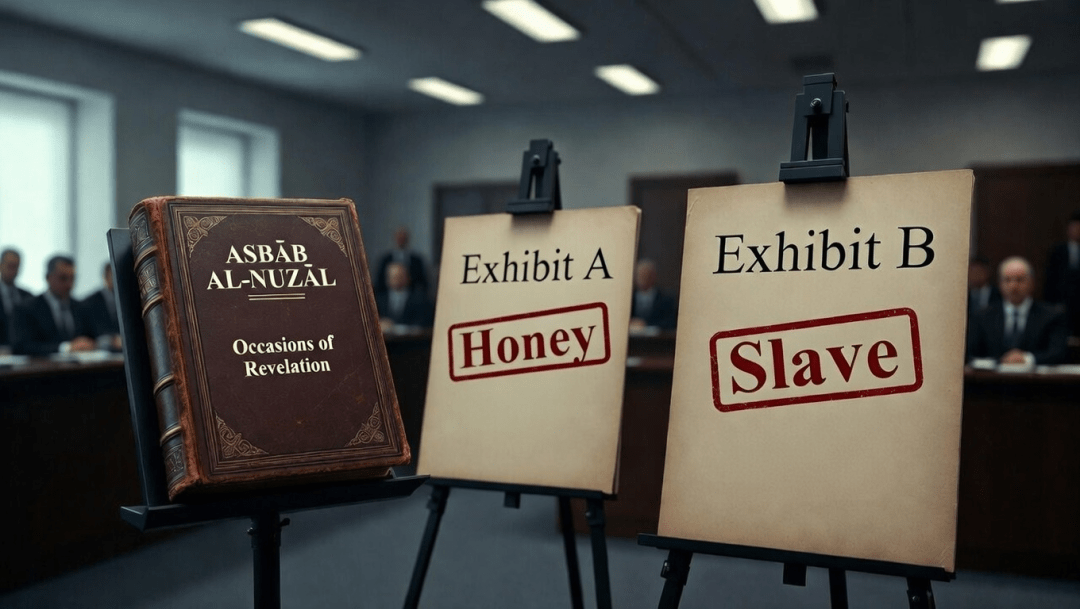

To answer these questions, we will examine the asbab al-nuzul material surrounding two verses — Quran 66:1 and 9:113—and trace the contradictions that emerge not between weak (daif) and strong reports, but between the strongest authentic (Sahih) reports the tradition has to offer.

Case Study One: Quran 66:1 & What Was Prohibited

The Verse

Sura al-Tahrim (Chapter 66), verse 1, reads:

[Quran 66:1] O you prophet, why do you prohibit what Allah has made lawful for you, just to please your wives? Allah is Forgiver, Merciful.

يَـٰٓأَيُّهَا ٱلنَّبِىُّ لِمَ تُحَرِّمُ مَآ أَحَلَّ ٱللَّهُ لَكَ تَبْتَغِى مَرْضَاتَ أَزْوَٰجِكَ وَٱللَّهُ غَفُورٌ رَّحِيمٌ

The verse addresses the Prophet directly, reproving him for declaring something lawful (halal) to be prohibited (haram) for himself in order to appease his wives. Its general import is clear: a divine correction of a personal vow or self-imposed prohibition. What the asbab al-nuzul literature cannot agree upon, however, is the most basic factual question the verse raises—namely, what was the thing the Prophet had forbidden himself?

The Narrations: Three Incompatible Occasions for a Single Verse

Narration One: The Honey Incident — Zainab’s House (Abu Dawud 3714)

The first and most widely cited account attributes the verse to an episode involving honey. It is preserved in Sunan Abi Dawud (3714), transmitted through the chain: al-Hasan ibn ‘Ali ← Abu Usamah ← Hisham ← his father (‘Urwah ibn al-Zubayr) ← ‘A’ishah.

‘A’ishah said that the prophet ﷺ used to stay with Zainab, daughter of Jahsh, and drink honey. I and Hafsah counseled each other that if the Prophet ﷺ enters upon any of us, she must say: I find the smell of gum (maghafir) from you. He then entered upon one of them; she said that to him. Thereupon he said: No, I drank honey at (the house of) Zainab daughter of Jahsh, and I will not do it again. Then the following verse came down: “O Prophet! Why holdest thou to be forbidden that which Allah has made lawful to thee?” … “If you two turn in repentance to Allah” refers to Hafsah and ‘A’ishah, and the verse: “When the Prophet disclosed a matter in confidence to one of his consorts” refers to the statement of the Prophet ﷺ: No, I drank honey.

حَدَّثَنَا أَحْمَدُ بْنُ مُحَمَّدِ بْنِ حَنْبَلٍ، حَدَّثَنَا حَجَّاجُ بْنُ مُحَمَّدٍ، قَالَ قَالَ ابْنُ جُرَيْجٍ عَنْ عَطَاءٍ، أَنَّهُ سَمِعَ عُبَيْدَ بْنَ عُمَيْرٍ، قَالَ سَمِعْتُ عَائِشَةَ، – رضى الله عنها – زَوْجَ النَّبِيِّ صلى الله عليه وسلم تُخْبِرُ أَنَّ النَّبِيَّ صلى الله عليه وسلم كَانَ يَمْكُثُ عِنْدَ زَيْنَبَ بِنْتِ جَحْشٍ فَيَشْرَبُ عِنْدَهَا عَسَلاً فَتَوَاصَيْتُ أَنَا وَحَفْصَةُ أَيَّتُنَا مَا دَخَلَ عَلَيْهَا النَّبِيُّ صلى الله عليه وسلم فَلْتَقُلْ إِنِّي أَجِدُ مِنْكَ رِيحَ مَغَافِيرَ فَدَخَلَ عَلَى إِحْدَاهُنَّ فَقَالَتْ لَهُ ذَلِكَ فَقَالَ ” بَلْ شَرِبْتُ عَسَلاً عِنْدَ زَيْنَبَ بِنْتِ جَحْشٍ وَلَنْ أَعُودَ لَهُ ” . فَنَزَلَتْ { لِمَ تُحَرِّمُ مَا أَحَلَّ اللَّهُ لَكَ تَبْتَغِي } إِلَى { إِنْ تَتُوبَا إِلَى اللَّهِ } لِعَائِشَةَ وَحَفْصَةَ رضى الله عنهما { وَإِذْ أَسَرَّ النَّبِيُّ إِلَى بَعْضِ أَزْوَاجِهِ حَدِيثًا } لِقَوْلِهِ ” بَلْ شَرِبْتُ عَسَلاً ” .

Sunan Abi Dawud 3714

https://sunnah.com/abudawud:3714

In this account, the prohibited item is honey, the wife at whose home it was consumed is Zainab bint Jahsh, and the conspirators who manipulated the Prophet into forswearing it are ‘A’ishah and Hafsah.

Narration Two: The Honey Incident — Hafsah’s House (Abu Dawud 3715)

The same collection, just one hadith later, preserves a variant that subtly but materially contradicts the first:

‘A’ishah said: The Messenger of Allah ﷺ liked sweet meats and honey. The narrator then mentioned a part of the tradition mentioned above. The Messenger of Allah ﷺ felt it hard on him to find smell from him. In this tradition Saudah said: but you ate gum? He said: No, I drank honey. Hafsah gave it to me to drink. I said: Its bees ate ‘urfut.

حَدَّثَنَا الْحَسَنُ بْنُ عَلِيٍّ، حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو أُسَامَةَ، عَنْ هِشَامٍ، عَنْ أَبِيهِ، عَنْ عَائِشَةَ، قَالَتْ كَانَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم يُحِبُّ الْحَلْوَاءَ وَالْعَسَلَ . فَذَكَرَ بَعْضَ هَذَا الْخَبَرِ . وَكَانَ النَّبِيُّ صلى الله عليه وسلم يَشْتَدُّ عَلَيْهِ أَنْ تُوجَدَ مِنْهُ الرِّيحُ . وَفِي الْحَدِيثِ قَالَتْ سَوْدَةُ بَلْ أَكَلْتَ مَغَافِيرَ . قَالَ “ بَلْ شَرِبْتُ عَسَلاً سَقَتْنِي حَفْصَةُ ” . فَقُلْتُ جَرَسَتْ نَحْلُهُ الْعُرْفُطَ .

Sunan Abi Dawud 3715

https://sunnah.com/abudawud:3715

Here the honey was given to the Prophet by Hafsah herself, not consumed by him independently at Zainab’s house. The wife who first confronts him with the smell complaint is Saudah, not one of the two conspirators from the previous version. The same transmitted chain—through Hisham ibn ‘Urwah from his father from ‘A’ishah—produces a meaningfully different scene. The wife who serves the honey, the wife who first raises the complaint, and the domestic setting of the exchange all differ between the two consecutive narrations in the same collection.

Narration Three: A Female Slave — Not Honey at All (al-Nasa’i 3959)

The third narration, preserved in Sunan al-Nasa’i (3959), transmitted through the chain: Ibrahim ibn Yunus ibn Muhammad ← his father ← Hammad ibn Salamah ← Thabit ← Anas (ibn Malik, a Companion), presents an occasion for the verse’s revelation so different from the honey story that the two cannot be reconciled as variant recollections of the same event:

It was narrated from Anas, that the Messenger of Allah had a female slave with whom he had intercourse, but ‘A’ishah and Hafsah would not leave him alone until he said that she was forbidden for him. Then Allah, the Mighty and Sublime, revealed: “O Prophet! Why do you forbid (for yourself) that which Allah has allowed to you.” until the end of the Verse.

أَخْبَرَنِي إِبْرَاهِيمُ بْنُ يُونُسَ بْنِ مُحَمَّدٍ، حَرَمِيٌّ – هُوَ لَقَبُهُ – قَالَ حَدَّثَنَا أَبِي قَالَ، حَدَّثَنَا حَمَّادُ بْنُ سَلَمَةَ، عَنْ ثَابِتٍ، عَنْ أَنَسٍ، أَنَّ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم كَانَتْ لَهُ أَمَةٌ يَطَؤُهَا فَلَمْ تَزَلْ بِهِ عَائِشَةُ وَحَفْصَةُ حَتَّى حَرَّمَهَا عَلَى نَفْسِهِ فَأَنْزَلَ اللَّهُ عَزَّ وَجَلَّ { يَا أَيُّهَا النَّبِيُّ لِمَ تُحَرِّمُ مَا أَحَلَّ اللَّهُ لَكَ } إِلَى آخِرِ الآيَةِ .

Sunan al-Nasa’i 3959

https://sunnah.com/nasai:3959

The prohibited thing, in this narration, is not honey. It is a female slave. The same two wives, ‘A’ishah and Hafsah, are the instigating parties—the one consistent element across the accounts — but everything substantive about what was prohibited differs entirely.

The Anatomy of the Inconsistencies

The contradictions in the asbab al-nuzul material for Q. 66:1 are not peripheral. They concern the very substance of the verse—the identity of what was prohibited—which is the single most important factual question one would expect to find if Hadith genuinely served the purpose its adherents claim it does. Honey and a female slave are not alternative details of the same event. They describe categorically different situations, carrying different legal and moral implications. A man forswearing a pleasant drink at the urging of jealous wives and a man declaring his concubine sexually forbidden to himself are entirely different acts, and a divine reprimand addressed to one situation cannot simultaneously be a reprimand addressed to the other.

It is also telling that the two honey-based narrations, ostensibly the closest to one another, disagree on which wife served the honey (Zainab versus Hafsah), which wife first deployed the smell-complaint to manipulate the Prophet (an unnamed one of the conspirators versus Saudah), and therefore what the private domestic scene looked like. ‘A’ishah is reported as the source in both cases—meaning the discrepancies arise not between different witnesses but within the testimony attributed to a single witness transmitted through the same chain. That a narrator as authoritative as ‘A’ishah, and a chain as well-regarded as Hisham from his father, should produce internally inconsistent accounts is precisely the kind of problem that chain-based criticism is ill-equipped to detect. Isnad authentication at best can only provide insight into the formal integrity of a chain; it cannot adjudicate between two contradictory versions transmitted through the same chain.

The narration from Anas — which replaces the honey episode entirely with an incident involving a female slave — comes through a different Companion and an independent chain of transmission. It is not a variation of the honey report but a competing origin account, and it too is graded ṣaḥīḥ. Each tradition claims to preserve the occasion of revelation for the same verse, yet the two accounts are mutually exclusive. If both are deemed authentic, the authentication mechanism is shown not to accomplish what it claims, because both reports cannot simultaneously be historically true. This assumes, of course, that either report is historically reliable at all. It remains possible that neither reflects the original event, and that both emerged retrospectively, as part of the broader pattern seen in much of the asbāb al-nuzūl literature, where explanatory narratives were generated after the fact to anchor verses in concrete historical settings.

Case Study Two: Quran 9:113

The Verse

Sura al-Barã’ah, also known as al-Tawbah (Chapter 9), verse 113, reads:

[Quran 9:113] Neither the prophet, nor those who believe shall ask forgiveness for the idol worshipers, even if they were their nearest of kin, once they realize that they are destined for Hell.

مَا كَانَ لِلنَّبِىِّ وَٱلَّذِينَ ءَامَنُوٓا۟ أَن يَسْتَغْفِرُوا۟ لِلْمُشْرِكِينَ وَلَوْ كَانُوٓا۟ أُو۟لِى قُرْبَىٰ مِنۢ بَعْدِ مَا تَبَيَّنَ لَهُمْ أَنَّهُمْ أَصْحَـٰبُ ٱلْجَحِيمِ

This verse, in classical Islamic scholarship, is understood as a divine prohibition against seeking God’s forgiveness on behalf of those who died outside the fold of Islam. The asbab al-nuzul literature provides multiple occasions for its revelation, and it is here that the inconsistencies begin.

The Narrations: Four Distinct Occasions for a Single Verse

Narration One: The Deathbed Scene of Abu Talib (Bukhari 4675)

The first and most prominent narrative is preserved in Sahih al-Bukhari (hadith 4675), transmitted through the chain: Ishaq ibn Ibrahim ← ‘Abd al-Razzaq ← Ma’mar ← al-Zuhri ← Sa’id ibn al-Musayyib ← his father (al-Musayyib ibn Hazn).

Ishaq ibn Ibrahim narrated to us, ‘Abd al-Razzaq narrated to us, Ma‘mar informed us, from al-Zuhri, from Sa‘id ibn al-Musayyib, from his father, who said:

When death approached Abu Talib, the Prophet ﷺ entered upon him, and with him were Abu Jahl and ‘Abdullah ibn Abi Umayyah. The Prophet ﷺ said:

“O my uncle, say: ‘There is no god except Allah.’ I will argue on your behalf with it before Allah.”

Abu Jahl and ‘Abdullah ibn Abi Umayyah said: “O Abu Talib, will you turn away from the religion of ‘Abd al-Muttalib?”

The Prophet ﷺ continued saying to him: “I will surely seek forgiveness for you unless I am forbidden from doing so.”

Then the verse was revealed:

“It is not for the Prophet and those who believe to seek forgiveness for the polytheists, even if they are close relatives, after it has become clear to them that they are companions of the Hellfire.” (Quran 9:113)

حَدَّثَنَا إِسْحَاقُ بْنُ إِبْرَاهِيمَ، حَدَّثَنَا عَبْدُ الرَّزَّاقِ، أَخْبَرَنَا مَعْمَرٌ، عَنِ الزُّهْرِيِّ، عَنْ سَعِيدِ بْنِ الْمُسَيَّبِ، عَنْ أَبِيهِ، قَالَ لَمَّا حَضَرَتْ أَبَا طَالِبٍ الْوَفَاةُ دَخَلَ عَلَيْهِ النَّبِيُّ صلى الله عليه وسلم وَعِنْدَهُ أَبُو جَهْلٍ وَعَبْدُ اللَّهِ بْنُ أَبِي أُمَيَّةَ، فَقَالَ النَّبِيُّ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” أَىْ عَمِّ قُلْ لاَ إِلَهَ إِلاَّ اللَّهُ. أُحَاجُّ لَكَ بِهَا عِنْدَ اللَّهِ ”. فَقَالَ أَبُو جَهْلٍ وَعَبْدُ اللَّهِ بْنُ أَبِي أُمَيَّةَ يَا أَبَا طَالِبٍ، أَتَرْغَبُ عَنْ مِلَّةِ عَبْدِ الْمُطَّلِبِ. فَقَالَ النَّبِيُّ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” لأَسْتَغْفِرَنَّ لَكَ مَا لَمْ أُنْهَ عَنْكَ ”. فَنَزَلَتْ {مَا كَانَ لِلنَّبِيِّ وَالَّذِينَ آمَنُوا أَنْ يَسْتَغْفِرُوا لِلْمُشْرِكِينَ وَلَوْ كَانُوا أُولِي قُرْبَى مِنْ بَعْدِ مَا تَبَيَّنَ لَهُمْ أَنَّهُمْ أَصْحَابُ الْجَحِيمِ}

Sahih al-Bukhari 4675

https://sunnah.com/bukhari:4675

This version is notable for what it does not include: it presents the Prophet’s promise to seek forgiveness and states that the verse was revealed in response, but does not record Abu Talib’s final words explicitly, though the implication is clear enough that he died without pronouncing the shahada.

Narration Two: The Same Scene, Expanded (Muslim 24a)

Sahih Muslim (Hadith 24a) preserves a more detailed account of the same episode, transmitted through the chain: Harmalah ibn Yahya al-Tujibi ← ‘Abdullah ibn Wahb ← Yunus ← Ibn Shihab (al-Zuhri) ← Sa’id ibn al-Musayyib ← his father.

Harmalah ibn Yahya al-Tujibi narrated to me, ‘Abdullah ibn Wahb informed us, he said: Yunus informed me, from Ibn Shihab, who said: Sa‘id ibn al-Musayyib informed me, from his father, who said:

When death approached Abu Talib, the Messenger of Allah ﷺ came to him and found with him Abu Jahl and ‘Abdullah ibn Abi Umayyah ibn al-Mughirah. The Messenger of Allah ﷺ said:

“O my uncle, say: ‘There is no god except Allah’—a word by which I may testify for you before Allah.”

Abu Jahl and ‘Abdullah ibn Abi Umayyah said: “O Abu Talib, will you turn away from the religion of ‘Abd al-Muttalib?”

The Messenger of Allah ﷺ continued presenting it to him and repeating that statement to him until the last thing Abu Talib said to them was that he remained upon the religion of ‘Abd al-Muttalib, and he refused to say, ‘There is no god except Allah.’

Then the Messenger of Allah ﷺ said:

“By Allah, I will certainly seek forgiveness for you unless I am forbidden from doing so.”

So Allah, Mighty and Majestic, revealed:

“It is not for the Prophet and those who believe to seek forgiveness for the polytheists, even if they are close relatives, after it has become clear to them that they are companions of the Hellfire.” (Quran 9:113)

And Allah also revealed concerning Abu Talib, saying to the Messenger of Allah ﷺ:

“Indeed, you do not guide whom you love, but Allah guides whom He wills, and He knows best those who are guided.” (Quran 28:56)

وَحَدَّثَنِي حَرْمَلَةُ بْنُ يَحْيَى التُّجِيبِيُّ، أَخْبَرَنَا عَبْدُ اللَّهِ بْنُ وَهْبٍ، قَالَ أَخْبَرَنِي يُونُسُ، عَنِ ابْنِ شِهَابٍ، قَالَ أَخْبَرَنِي سَعِيدُ بْنُ الْمُسَيَّبِ، عَنْ أَبِيهِ، قَالَ لَمَّا حَضَرَتْ أَبَا طَالِبٍ الْوَفَاةُ جَاءَهُ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم فَوَجَدَ عِنْدَهُ أَبَا جَهْلٍ وَعَبْدَ اللَّهِ بْنَ أَبِي أُمَيَّةَ بْنِ الْمُغِيرَةِ فَقَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” يَا عَمِّ قُلْ لاَ إِلَهَ إِلاَّ اللَّهُ . كَلِمَةً أَشْهَدُ لَكَ بِهَا عِنْدَ اللَّهِ ” . فَقَالَ أَبُو جَهْلٍ وَعَبْدُ اللَّهِ بْنُ أَبِي أُمَيَّةَ يَا أَبَا طَالِبٍ أَتَرْغَبُ عَنْ مِلَّةِ عَبْدِ الْمُطَّلِبِ . فَلَمْ يَزَلْ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم يَعْرِضُهَا عَلَيْهِ وَيُعِيدُ لَهُ تِلْكَ الْمَقَالَةَ حَتَّى قَالَ أَبُو طَالِبٍ آخِرَ مَا كَلَّمَهُمْ هُوَ عَلَى مِلَّةِ عَبْدِ الْمُطَّلِبِ . وَأَبَى أَنْ يَقُولَ لاَ إِلَهَ إِلاَّ اللَّهُ . فَقَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم ” أَمَا وَاللَّهِ لأَسْتَغْفِرَنَّ لَكَ مَا لَمْ أُنْهَ عَنْكَ ” . فَأَنْزَلَ اللَّهُ عَزَّ وَجَلَّ { مَا كَانَ لِلنَّبِيِّ وَالَّذِينَ آمَنُوا أَنْ يَسْتَغْفِرُوا لِلْمُشْرِكِينَ وَلَوْ كَانُوا أُولِي قُرْبَى مِنْ بَعْدِ مَا تَبَيَّنَ لَهُمْ أَنَّهُمْ أَصْحَابُ الْجَحِيمِ} . وَأَنْزَلَ اللَّهُ تَعَالَى فِي أَبِي طَالِبٍ فَقَالَ لِرَسُولِ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم { إِنَّكَ لاَ تَهْدِي مَنْ أَحْبَبْتَ وَلَكِنَّ اللَّهَ يَهْدِي مَنْ يَشَاءُ وَهُوَ أَعْلَمُ بِالْمُهْتَدِينَ}.

Sahih Muslim 24a

https://sunnah.com/muslim:24a

The Muslim version adds significant information absent from Bukhari: it explicitly records Abu Talib’s final declaration—that he remained on the religion of ‘Abd al-Muttalib — and appends a second verse (Q. 28:56) as also being revealed on account of this event. That the same chain through al-Zuhri from Sa’id ibn al-Musayyib from his father yields meaningfully different content in the two most authoritative collections is itself a point deserving attention.

Narration Three: A Different Occasion Entirely (al-Hakim 3290)

The third narration, preserved by al-Hakim in his Mustadrak (no. 3290) and classified as sahih al-isnad by al-Hakim, with al-Dhahabi’s endorsement, presents an entirely different occasion for the same verse’s revelation. The chain runs: Abu ‘Ali al-Husayn ibn ‘Ali al-Hafiz ← al-Fadl ibn Muhammad al-Janadi ← Abu Humah al-Yamani ← Sufyan ibn ‘Uyaynah ← ‘Amr ibn Dinar ← Jabir (ibn ‘Abdullah, a Companion).

Abu ‘Ali al-Husayn ibn ‘Ali al-Hafiz informed me; al-Fadl ibn Muhammad al-Janadi in Mecca narrated to us; Abu Humah al-Yamani narrated to us; Sufyan ibn ‘Uyaynah narrated to us, from ‘Amr ibn Dinar, from Jabir, who said:

When Abu Talib died, the Messenger of Allah ﷺ said:

“May Allah have mercy on you and forgive you, O my uncle. I will continue to seek forgiveness for you until Allah forbids me.”

Then the Muslims began seeking forgiveness for their deceased relatives who had died as polytheists. So Allah, Most High, revealed:

“It is not for the Prophet and those who believe to seek forgiveness for the polytheists, even if they are close relatives, after it has become clear to them that they are companions of the Hellfire.” (Quran 9:113)

[Al-Hakim said:] “This hadith has a sound chain (sahih al-isnad), though al-Bukhari and Muslim did not record it.”

And Abu ‘Ali said to us afterward: “I do not know anyone who connected (i.e., transmitted with a complete chain) this hadith from Sufyan other than Abu Humah al-Yamani, and he is trustworthy. The other companions of Ibn ‘Uyaynah transmitted it in mursal form (with a missing link). It is sound.”

الحاكم:٣٢٩٠ – أَخْبَرَنِي أَبُو عَلِيٍّ الْحُسَيْنُ بْنُ عَلِيٍّ الْحَافِظُ أَنْبَأَ الْفَضْلُ بْنُ مُحَمَّدٍ الْجَنَدِيُّ بِمَكَّةَ ثنا أَبُو حُمَةَ الْيَمَانِيُّ ثنا سُفْيَانُ بْنُ عُيَيْنَةَ عَنْ عَمْرِو بْنِ دِينَارٍ عَنْ جَابِرٍ قَالَ لَمَّا مَاتَ أَبُو طَالِبٍ

قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ ﷺ «رَحِمَكَ اللَّهُ وَغَفَرَ لَكَ يَا عَمُّ وَلَا أَزَالُ أَسْتَغْفِرُ لَكَ حَتَّى يَنْهَانِيَ اللَّهُ ﷻ» فَأَخَذَ الْمُسْلِمُونَ يَسْتَغْفِرُونَ لِمَوْتَاهُمُ الَّذِينَ مَاتُوا وَهُمْ مُشْرِكُونَ فَأَنْزَلَ اللَّهُ تَعَالَى {مَا كَانَ لِلنَّبِيِّ وَالَّذِينَ آمَنُوا أَنْ يَسْتَغْفِرُوا لِلْمُشْرِكِينَ وَلَوْ كَانُوا أُولِي قُرْبَى مِنْ بَعْدِ مَا تَبَيَّنَ لَهُمْ أَنَّهُمْ أَصْحَابُ الْجَحِيمِ} [التوبة 113]

«هَذَا حَدِيثٌ صَحِيحُ الْإِسْنَادِ وَلَمْ يُخْرِجَاهُ» وَقَالَ لَنَا أَبُو عَلِيٍّ عَلَى أَثَرِهِ لَا أَعْلَمُ أَحَدًا وَصَلَ هَذَا الْحَدِيثَ عَنْ سُفْيَانَ غَيْرَ أَبِي حُمَةَ الْيَمَانِيِّ وَهُوَ ثِقَةٌ وَقَدْ أَرْسَلَهُ أَصْحَابُ ابْنِ عُيَيْنَةَ صحيح

Al-Hakim (3290)

hakim:3290

Sahih (Dhahabī)

Where Bukhari and Muslim record the verse as being revealed at the deathbed scene itself, the Jabir narration places the triggering event after Abu Talib’s death, when a broader practice of intercession spread among the Muslim community. The verse, in this version, is not a response to the Prophet’s private promise to a dying man, but a correction to a communal religious practice that developed in the aftermath of that death.

Narration Four: An Entirely Different Context (al-Hakim 3289)

The fourth narration, also in al-Hakim’s Mustadrak (no. 3289) and likewise endorsed as sahih by al-Dhahabi, removes the episode from the Abu Talib context entirely. Its chain runs through various paths converging on Sufyan al-Thawri ← Abu Ishaq ← Abu al-Khalil ← ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib.

Abu ‘Abdullah Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Saffar narrated to us; Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Barti narrated to us; Abu Nu‘aym and Abu Hudhayfah both said: Sufyan narrated to us.

And ‘Ali ibn ‘Isa ibn Ibrahim informed me; al-Husayn ibn Muhammad ibn Ziyad narrated to us; ‘Uthman ibn Abi Shaybah narrated to us; Waki‘ narrated to us; Sufyan narrated to us, from Abu Ishaq, from Abu al-Khalil, from ‘Ali, who said:

I heard a man seeking forgiveness for his parents while they were polytheists. So I said, “Do not seek forgiveness for your parents while they are polytheists.”

He replied, “Did not Abraham seek forgiveness for his father while he was a polytheist?”

So I mentioned that to the Prophet ﷺ, and then the verse was revealed:

“It is not for the Prophet and those who believe to seek forgiveness for the polytheists, even if they are close relatives, after it has become clear to them that they are companions of the Hellfire. And Abraham’s seeking forgiveness for his father was only because of a promise he had made to him; but when it became clear to him that he was an enemy to Allah, he dissociated himself from him. Indeed, Abraham was tender-hearted and forbearing.”

(Quran 9:113–114)

الحاكم:٣٢٨٩ – أَخْبَرَنَا أَبُو عَبْدِ اللَّهِ مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ عَبْدِ الصَّفَّارُ ثنا أَحْمَدُ بْنُ مُحَمَّدٍ الْبَرْتِيُّ ثنا أَبُو نُعَيْمٍ وَأَبُو حُذَيْفَةَ قَالَا ثنا سُفْيَانُ وَأَخْبَرَنِي عَلِيُّ بْنُ عِيسَى بْنِ إِبْرَاهِيمَ ثنا الْحُسَيْنُ بْنُ مُحَمَّدِ بْنِ زِيَادٍ ثنا عُثْمَانُ بْنُ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ ثنا وَكِيعٌ ثنا سُفْيَانُ عَنْ أَبِي إِسْحَاقَ عَنْ أَبِي الْخَلِيلِ عَنْ عَلِيٍّ قَالَ

سَمِعْتُ رَجُلًا يَسْتَغْفِرُ لِأَبَوَيْهِ وَهُمَا مُشْرِكَانِ فَقُلْتُ لَا تَسْتَغْفِرْ لِأَبَوَيْكَ وَهُمَا مُشْرِكَانِ فَقَالَ أَلَيْسَ قَدِ اسْتَغْفَرَ إِبْرَاهِيمُ لِأَبِيهِ وَهُوَ مُشْرِكٌ؟ فَذَكَرْتُهُ لِلنَّبِيِّ ﷺ فَنَزَلَتْ {مَا كَانَ لِلنَّبِيِّ وَالَّذِينَ آمَنُوا أَنْ يَسْتَغْفِرُوا لِلْمُشْرِكِينَ وَلَوْ كَانُوا أُولِي قُرْبَى مِنْ بَعْدِ مَا تَبَيَّنَ لَهُمْ أَنَّهُمْ أَصْحَابُ الْجَحِيمِ وَمَا كَانَ اسْتِغْفَارُ إِبْرَاهِيمَ لِأَبِيهِ إِلَّا عَنْ مَوْعِدَةٍ وَعَدَهَا إِيَّاهُ فَلَمَّا تَبَيَّنَ لَهُ أَنَّهُ عَدُوٌّ لِلَّهِ تَبَرَّأَ مِنْهُ إِنَّ إِبْرَاهِيمَ لَأَوَّاهٌ حَلِيمٌ} [التوبة 114]

Al-Hakim (3289)

hakim:3289

Sahih (Dhahabī)

This report, narrated on the authority of ‘Ali himself, attributes the revelation of 9:113–114 to a completely separate incident: an anonymous man’s argument with ‘Ali about the permissibility of seeking forgiveness for polytheist parents, grounded in a comparison to Abraham’s intercession for his father Azar. There is no Abu Talib, no deathbed, no dying uncle, and no communal outbreak of intercession. The verse here is a response to a theological dispute about prophetic precedent.

The Anatomy of the Inconsistencies in 9:113

The contradictions in the asbab al-nuzul material for Q. 9:113 operate at several distinct levels. The triggering event differs across narrations: Bukhari and Muslim agree that the verse was revealed in response to the Prophet’s promise at Abu Talib’s deathbed, while the Jabir narration in al-Hakim places the revelation after the death and in response to a community-wide practice of intercession, and the ‘Ali narration places it in an entirely different context with no necessary connection to Abu Talib at all. These are not minor variations in detail; they are fundamentally different events, different settings, different interlocutors, and different precipitating causes for the same few words of divine speech.

Even between Bukhari and Muslim, which share the same underlying chain through al-Zuhri from Sa’id ibn al-Musayyib from his father, the accounts differ materially. The Muslim version includes Abu Talib’s final declaration, absent in Bukhari, and adds Q. 28:56 as a second verse revealed on the same occasion, something Bukhari does not record. If both reports faithfully transmit the same chain to the same source, the discrepancy in content demands explanation that isnad analysis alone cannot supply.

The Classical Attempt at Harmonization

Classical Islamic scholarship did not ignore these contradictions. The discipline of ta’arud wa’l-tarjih — reconciling apparently conflicting reports — was developed precisely to manage such tensions. When confronted with multiple sahih reports offering different occasions for the same revelation, the standard methodological move is to argue that the verse was revealed in response to multiple, overlapping occasions (ta’addud al-asbab): the same divine ruling was prompted by several converging circumstances, and all of the reports are true simultaneously.

The most sophisticated version of this argument, as applied to Q. 9:113, runs roughly as follows. The Abu Talib deathbed account is taken as the primary trigger. The community’s subsequent practice of intercession for deceased polytheist relatives is treated as a secondary or reinforcing occasion that confirmed the need for the prohibition to be stated explicitly. The ‘Ali narration is understood as yet another circumstance in which the same prohibition needed to be grounded in further explanation, hence the additional verse about Abraham’s exception. On this reading, the several narrations each capture a different facet of a multi-layered divine response.

This harmonization has a certain elegance, and within the internal logic of the tradition it is not without coherence. Yet even granting this framework its most charitable reading, there remains a serious problem that no appeal to ta’addud al-asbab can resolve.

The Chronological Wall: Sura 9 as the Last Complete Revelation

The harmonization strategy treats the multiple occasions as overlapping and mutually reinforcing — but this requires that Q. 9:113 was revealed at a time when all of these occasions could plausibly have occurred within a proximate window. The death of Abu Talib is traditionally dated to approximately 619 CE, about three years before the Hijrah in 622. If the verse was indeed revealed in response to Abu Talib’s death, one would have expected this verse to come within that time period.

This is where the problem becomes intractable. Because the same hadith tradition that preserves the asbab al-nuzul accounts for 9:113 also preserves reports establishing the chronological position of Sura al-Barã’ah as the last Sura to be revealed in whole shortly before the Prophet’s passing. These reports create a contradiction with the claimed occasion that cannot be harmonized away.

Sahih al-Bukhari (4364) and Sahih Muslim (1618c) both preserve a report from al-Bara’ ibn ‘Azib:

‘Abdullah ibn Raja’ narrated to me; Isra’il narrated to us, from Abu Ishaq, from al-Bara’ (may Allah be pleased with him), who said:

The last surah that was revealed in full was Barā’ah (Surah al-Tawbah), and the last verse that was revealed was the closing of Surah al-Nisa’:

“They ask you for a legal ruling. Say: Allah gives you a ruling concerning the kalālah (one who leaves neither ascendants nor descendants as heirs).” (Quran 4:176).

حَدَّثَنِي عَبْدُ اللَّهِ بْنُ رَجَاءٍ، حَدَّثَنَا إِسْرَائِيلُ، عَنْ أَبِي إِسْحَاقَ، عَنِ الْبَرَاءِ ـ رضى الله عنه ـ قَالَ آخِرُ سُورَةٍ نَزَلَتْ كَامِلَةً بَرَاءَةٌ، وَآخِرُ سُورَةٍ نَزَلَتْ خَاتِمَةُ سُورَةِ النِّسَاءِ {يَسْتَفْتُونَكَ قُلِ اللَّهُ يُفْتِيكُمْ فِي الْكَلاَلَةِ}

Sahih al-Bukhari 4364

https://sunnah.com/bukhari:4364

Ishaq ibn Ibrahim al-Hanzali narrated to us; ‘Isa — who is Ibn Yunus — informed us; Zakariyya narrated to us, from Abu Ishaq, from al-Bara’, that:

The last surah that was revealed in full was Surah al-Tawbah, and the last verse that was revealed was the verse concerning al-kalālah (inheritance of one who leaves neither parents nor children).

حَدَّثَنَا إِسْحَاقُ بْنُ إِبْرَاهِيمَ الْحَنْظَلِيُّ، أَخْبَرَنَا عِيسَى، – وَهُوَ ابْنُ يُونُسَ – حَدَّثَنَا زَكَرِيَّاءُ، عَنْ أَبِي إِسْحَاقَ، عَنِ الْبَرَاءِ، أَنَّ آخِرَ، سُورَةٍ أُنْزِلَتْ تَامَّةً سُورَةُ التَّوْبَةِ وَأَنَّ آخِرَ آيَةٍ أُنْزِلَتْ آيَةُ الْكَلاَلَةِ .

Sahih Muslim 1618c

https://sunnah.com/muslim:1618c

The implication is stark. If Sura al-Barã’ah —the sura containing verse 113 — was the last complete sura to be revealed, then its verses, including 9:113, were among the final revelations of the Prophet’s career, delivered in or around 9–10 AH (630–632 CE). Abu Talib died in approximately 619 CE, some ten years earlier. A verse that was among the last in the entire Quran to be revealed cannot have been occasioned by an event that occurred a decade before the Prophet’s death.

The chronological wall does not only confront the Abu Talib deathbed narration. The ‘Ali narration in al-Hakim 3289 faces its own independent version of the same problem, one arising through an entirely different mechanism. In that account, an unnamed man defends his practice of seeking forgiveness for his polytheist parents by invoking Abraham’s intercession for his father as an unresolved precedent — a live theological question requiring prophetic adjudication. This framing only makes sense if Sura al-Mumtahanah (Chapter 60), verse 4, had not yet been revealed. That verse reads:

[Quran 60:4, Sahih International] You already have an excellent example in Abraham and those with him, when they said to their people, ‘We totally dissociate ourselves from you and whatever idols you worship besides Allah. We reject you. The enmity and hatred that has arisen between us and you will last until you believe in Allah alone.’ The only exception is when Abraham said to his father, ‘I will seek forgiveness for you,’ adding, ‘but I cannot protect you from Allah at all.’

Q. 60:4 addresses Abraham’s intercession for his father directly, presenting it not as a general open-ended precedent but as a mistake on his part — an act that Abraham himself eventually withdrew. Had this verse already been in the community’s possession, the man’s argument would have been a non-starter: the Qur’an had already qualified the very example he was citing. The fact that his invocation of Abraham is treated as a genuine theological challenge requiring a new revelation to settle implies that Q. 60:4 simply did not exist yet at the time of the exchange described.

Here, however, the tradition’s own chronological framework closes the argument against the narration. Sura al-Mumtahanah is traditionally placed as the ninety-first sura in the canonical ordering of revelation — a Medinan sura revealed well before the Prophet’s final years. Sura al-Tawbah, which the tradition places as the last complete sura revealed, postdates it. The ‘Ali narration therefore requires a scenario in which a member of the Medinan community treated an already-revealed Quranic verse as an unaddressed question, and in which that ostensibly settled matter then became the occasion for verses in the very last sura of the entire revelation. The narration’s internal logic does not survive contact with the tradition’s own sura chronology — and this is a conclusion the tradition itself supplies, without any recourse to external dating.

The Complexity Deepens: What Does “Last Complete Sura” Actually Mean?

One might attempt to deflect the above objection by arguing that al-Bara’s report should be read more narrowly: perhaps “the last sura revealed in full” (آخر سورة أنزلت تامة) means only that Sura al-Tawbah was the last to be completed as a literary unit, not that every individual verse within it was revealed near the end of the Prophet’s life. On this reading, earlier verses of the sura—including 9:113 — could theoretically have been delivered years before the sura was finalized in its current form.

This escape route, however, is closed by al-Bara’s own words within the same report. In Bukhari 4364, al-Bara’ makes two distinct claims alongside one another: that the last sura revealed in full was Sura al-Tawbah, and that the last portion of a sura to be revealed was the closing verses of Sura al-Nisa’ (Q. 4:176). The report reads:

Narrated Al-Bara: The last Sura which was revealed in full was Baraa (i.e. Sura-at-Tauba), and the last Sura (i.e. part of a Sura) which was revealed was the last Verses of Sura-an-Nisa’: — “They ask you for a legal decision. Say: Allah directs (thus) About those who have No descendants or ascendants As heirs.” (4.176)

حَدَّثَنِي عَبْدُ اللَّهِ بْنُ رَجَاءٍ، حَدَّثَنَا إِسْرَائِيلُ، عَنْ أَبِي إِسْحَاقَ، عَنِ الْبَرَاءِ ـ رضى الله عنه ـ قَالَ آخِرُ سُورَةٍ نَزَلَتْ كَامِلَةً بَرَاءَةٌ، وَآخِرُ سُورَةٍ نَزَلَتْ خَاتِمَةُ سُورَةِ النِّسَاءِ {يَسْتَفْتُونَكَ قُلِ اللَّهُ يُفْتِيكُمْ فِي الْكَلاَلَةِ}

Sahih al-Bukhari 4364

https://sunnah.com/bukhari:4364

The distinction al-Bara’ draws here is precise and deliberate. He uses “in full” (kamilatan) to describe Sura al-Tawbah, and separately identifies the closing of Sura al-Nisa’ as the last portion of a sura to come down. If “in full” were merely a way of saying “the last sura to be finalized after piecemeal delivery over time,” then the logical implication of his second claim would be that Sura al-Nisa’ was itself the last sura revealed — which is clearly not what he intends. The only reading that makes both halves of his statement coherent is that “in full” means the entire sura descended as a complete unit, in contrast to other suras whose verses arrived incrementally. Al-Bara’ is not hedging; he is drawing a categorical distinction between two modes of revelation. Sura al-Tawbah, on his account, came down whole — and it came down last.

The attempt to use “in full” as a loophole, to suggest that 9:113 might have been delivered years before the sura’s completion, therefore fails on the tradition’s own terms. The piecemeal-delivery reading is not available because al-Bara’ himself contrasts it with the other category he identifies in the same breath.

Ironically, even this clarified claim generates a further contradiction. Sahih Muslim (3024a) preserves a report from Ibn ‘Abbas that flatly contradicts al-Bara’s identification of the last sura:

Ubaidullah b. ‘Abdullah b. ‘Utba reported: Ibn Abbas said to me: Do you know-and in the words of Harun (another narrator): Are you aware of-the last Sura which was revealed in the Quran as a whole? I said: Yes,” When came the help from Allah and the victory” (cx.). Thereupon, he said: You have told the truth. And in the narration of Abu Shaiba (the words are): Do you know the Sura? And he did not mention the words” the last one”.

حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو بَكْرِ بْنُ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ، وَهَارُونُ بْنُ عَبْدِ اللَّهِ، وَعَبْدُ بْنُ حُمَيْدٍ، قَالَ عَبْدٌ أَخْبَرَنَا وَقَالَ الآخَرَانِ، حَدَّثَنَا جَعْفَرُ بْنُ عَوْنٍ، أَخْبَرَنَا أَبُو عُمَيْسٍ، عَنْ عَبْدِ الْمَجِيدِ بْنِ سُهَيْلٍ، عَنْ عُبَيْدِ اللَّهِ بْنِ عَبْدِ اللَّهِ بْنِ عُتْبَةَ، قَالَ قَالَ لِيَ ابْنُ عَبَّاسٍ تَعْلَمُ – وَقَالَ هَارُونُ تَدْرِي – آخِرَ سُورَةٍ نَزَلَتْ مِنَ الْقُرْآنِ نَزَلَتْ جَمِيعًا قُلْتُ نَعَمْ . { إِذَا جَاءَ نَصْرُ اللَّهِ وَالْفَتْحُ} قَالَ صَدَقْتَ . وَفِي رِوَايَةِ ابْنِ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ تَعْلَمُ أَىُّ سُورَةٍ . وَلَمْ يَقُلْ آخِرَ .

Sahih Muslim 3024a

https://sunnah.com/muslim:3024a

Here is a second Companion — Ibn ‘Abbas, the Prophet’s own cousin and one of the most celebrated transmitters of Quranic knowledge — testifying that the last complete sura to be revealed was not al-Tawbah but Sura al-Nasr (Chapter 110). Al-Bara’ says al-Tawbah; Ibn ‘Abbas says al-Nasr. Both reports are in Sahih Muslim, the very collection whose criterion of authentication is held to be among the most rigorous in the Islamic tradition.

What this cascade of contradictions reveals is that the question of which sura was revealed last, which verse was revealed last, and which events occasioned which revelations was not settled knowledge in the early community. The authenticated hadith themselves disagree — and their disagreements are preserved in the very sources that claim to transmit these testimonies correctly.

What the Contradictions Tell Us

The significance of these contradictions, taken together across both case studies, is not merely academic. They strike at the foundational claim of the asbab al-nuzul genre: that we can know, on the basis of transmitted reports, the specific historical circumstances that caused specific verses to be revealed.

The first case study, concerning Q. 66:1, demonstrates that the asbab al-nuzul literature cannot agree on something as elementary as what the forbidden thing was—a question the verse itself, in its very first sentence, presupposes has a concrete historical answer. Honey and a female slave are not alternative recollections of the same event. They describe categorically different situations with different legal and moral dimensions, and no harmonization strategy can make them the same occasion. The reports also reveal that contradictions can arise within the testimony attributed to a single witness through the same chain, meaning that isnad authentication—which evaluates the trustworthiness of transmitters—cannot detect discrepancies that originate in the content rather than the integrity of the chain.

The second case study, concerning Q. 9:113, adds a dimension the first does not: a chronological impossibility. The deathbed narration in Bukhari and Muslim places the verse’s revelation in the early Meccan period (~619 CE), while the same hadith tradition elsewhere certifies that Sura al-Tawbah was the last complete sura revealed, delivered near the end of the Medinan period (~630–632 CE). These two positions cannot both be true, and the ta’addud al-asbab framework has no mechanism to bridge a gap of approximately ten years. Multiplying causes is a theological move; reversing chronology is not.

Third, and most systemically, the disagreement between al-Bara’ and Ibn ‘Abbas about which sura was revealed last—two Companions, two irreconcilable positions, both preserved in Sahih Muslim—suggests that uncertainty about the chronology and occasions of revelation was endemic to the tradition from its earliest period. If those who had direct access to the revelatory process could not agree on something as observable as which sura was the last to be completed, the confidence with which later asbab al-nuzul reports claim to specify the exact precipitating event for individual verses becomes deeply difficult to justify.

The apparatus of isnad criticism—however sophisticated, however productive of genuine scholarly insight—was not able to prevent the preservation of irreconcilably contradictory accounts within its most authoritative repositories. It adjudicates the formal integrity of chains of transmission. It does not, and cannot, guarantee that the events those chains describe are historically coherent with one another or with the broader chronological framework the tradition itself supplies.

Conclusion: Narratives in Search of a Text

Taken together, the asbab al-nuzul material examined across these two verses presents a consistent pattern. In both cases, the reports do not converge on a single historical event from different angles, as independent eyewitness recollections of the same incident might be expected to do. Instead, they diverge—sometimes on peripheral details, sometimes on the most central facts, and in the case of Q. 9:113, on facts that cannot both be true within the same temporal universe. This is precisely the pattern one would expect if the narratives were not independent recollections of real events, but competing attempts to supply plausible origins for verses whose actual historical context had become unknown, disputed, or differently understood across different circles of transmission.

The process of working backward from a verse to a narrative that could explain it—finding in the life of the Prophet a scene that resonates thematically with the verse’s content—was not unique to any single transmitter or period. It was, to all appearances, a widespread and largely unconscious feature of early Islamic exegetical culture, one in which the desire to anchor divine speech in human history generated stories that gradually accumulated the authority of transmission. By the time those stories were subjected to isnad criticism and assigned grades of authenticity, the contradictions between them had already been fixed in place.

The contradictions examined here are not the product of weak chains or disputed narrators. They arise from the intersection of reports that each independently meet the tradition’s most rigorous standards of authentication. This is the more serious indictment: not that bad reports made it into the tradition, but that good reports—evaluated and certified by the most careful scholars the tradition produced—tell irreconcilable stories about the same verses, in the same authoritative collections, without resolution. The science of hadith cannot certify what it was never designed to certify: that the historical events described in “authenticated chains” are true, mutually consistent, or correctly attributed to the verses they purport to explain.

This failure is not incidental — it is structural. The hadith corpus was never designed to function as a chronological biography of the Prophet or as a systematic record of the context in which specific verses were revealed. Had that been its purpose, the reports themselves would have required it: they would have carried precise dates, identified locations, and embedded contextual markers as a matter of form, the way a legal document or a historical chronicle demands such anchors as a condition of its own reliability. Instead, hadith reports are structured around the transmission of random actions, inactions, or statements attributed to the Prophet with little, if any, contextual information. Additionally, their primary concern is the chain’s authority, not the chronological precision of the content. The genre was not built to carry the weight that asbab al-nuzul places upon it.

The timeline of the asbab al-nuzul literature makes this plain. It took over four and a half centuries after the Prophet’s death before al-Wahidi produced the first dedicated attempt to systematically match hadith reports to their supposed Quranic contexts, and nearly nine centuries before al-Suyuti undertook the second major effort. These were not men transcribing a received and settled record — they were scholars working backward through an enormous and contradictory corpus, exercising considerable editorial judgment to try to construct correspondences that the original transmitters had never organized with that purpose in mind. And even after those centuries of labor, drawing on the full breadth of the hadith tradition including its weakest and most disputed reports, the two definitive works between them can account for barely more than ten percent of the Quran. The other ninety percent simply has no recoverable occasion of revelation — not because the records were lost, but in all likelihood because the premise was always wrong: most verses were never tied to specific biographical moments in the first place, and the fraction that were attributed to such moments generated the contradictions this article has examined. The project of asbab al-nuzul does not illuminate the hadith corpus. It exposes it.

Related Articles: