Abstract

Human civilization advances through gradual cultural evolution: simple forms mature into complex ones through iterative refinement, failure, and learning. Every masterwork—from the Great Pyramid to the Divine Comedy—rests upon centuries of predecessors and prototypes. Yet the Quran appears to violate this iron law. Emerging from seventh-century Arabia, a culture with no tradition of written books, rudimentary script, and no literary infrastructure, it stands as the first Arabic prose work—and simultaneously the most mass-transmitted, most mass-memorized, and most influential book in the history of the world.

This article examines the historical anomaly of the Quran’s sudden appearance: a society that had not yet learned to write books produced what remains the defining standard of written Arabic. We explore Arabia’s pre-Islamic cultural context, the absence of literary precursors, and the systematic failure of standard explanations (genius within tradition, lost evidence, oral evolution, retrospective editing) to account for this emergence. The text exhibits not only unprecedented literary qualities but mathematical structures—precise word counts matching astronomical cycles, letter frequencies following complex patterns—that could not have been engineered without computational tools unavailable for thirteen centuries.

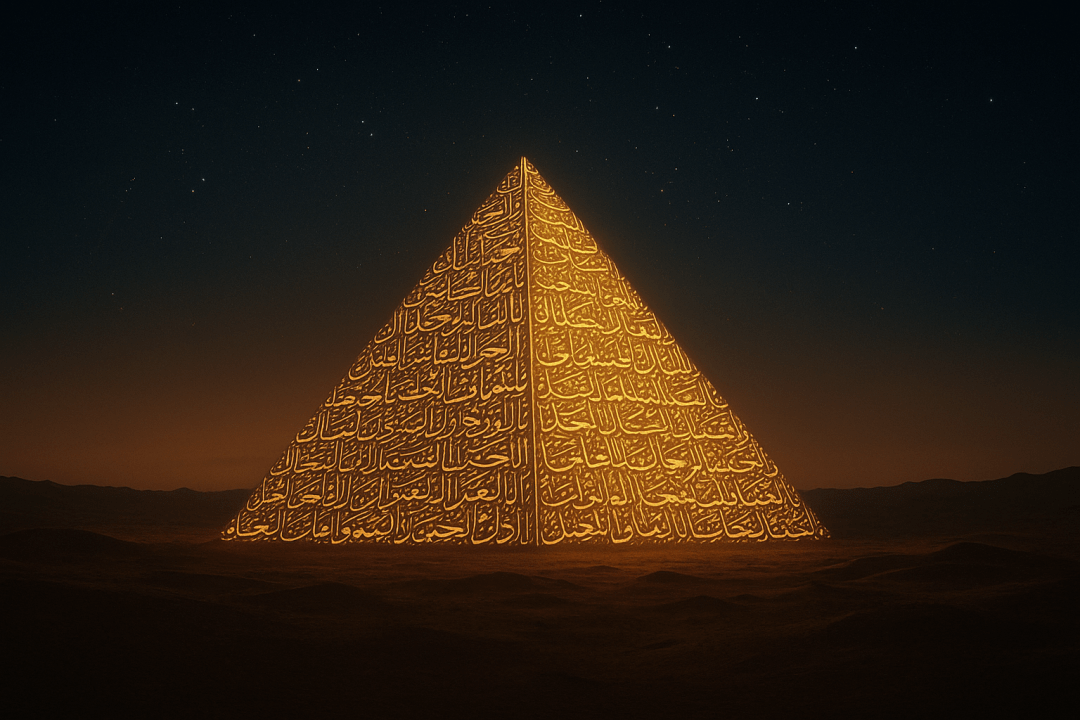

Imagine, for a moment, an alternate history. Archaeologists working in Alaska uncover something astonishing: a pyramid more magnificent than the current one in Giza stands before them in all its geometric perfection—millions of tons of limestone, aligned to true north within a fraction of a degree, its interior chambers arranged with mathematical precision. But as they excavate the surrounding plateau, they find something impossible.

There are no mastabas. No step pyramids. No collapsed prototypes. No evidence of experimentation, failure, or learning. The newly discovered Pyramid stands alone—the first pyramid ever built in that region, and already perfect.

Such a discovery would overturn everything we understand about human achievement. It would force us to conclude that either an unknown civilization had intervened, that evidence of predecessors had been mysteriously erased, or that the ancients of that region had achieved an inexplicable compression of centuries of development into a single generation.

We would know, with certainty, that something extraordinary had occurred—something that violated the normal laws of cultural evolution.

This hypothetical scenario is precisely analogous to what we observe in the historical record regarding the Quran.

The Law of Gradual Development

Across every domain of human achievement, we observe an iron law of cultural evolution: complexity emerges from simplicity through iterative refinement. Simple forms mature into sophisticated ones. Language develops from grunts to grammar; musical traditions evolve from chant to symphony; architectural forms progress from huts to temples to palaces. The trajectory is not always linear, but it is always cumulative.

Consider the evolution of writing itself. Cuneiform began as simple pictographic tallies pressed into clay by Sumerian accountants around 3200 BCE. Over a millennium, these marks evolved into a sophisticated system capable of recording epic poetry, legal codes, and astronomical observations. Egyptian hieroglyphics followed a similar arc—from tomb labels to the literature of the Middle Kingdom. The Greek alphabet, borrowed from Phoenician merchants, required centuries before it could carry the weight of Homer, then Plato, then Aristotle.

Even revolutionary breakthroughs follow this pattern. Newton’s calculus rested on Descartes’ coordinate geometry, which built upon centuries of Greek mathematics. Einstein’s relativity emerged from Maxwell’s equations and the puzzles of thermodynamics. Darwin synthesized Lyell’s geology, Malthus’s demographics, and decades of naturalist observation. Genius does not appear in a vacuum; it inherits an unfinished sentence and completes it.

The law holds across all domains. Gothic cathedrals required the Romanesque experiments that came before them. Jazz emerged from blues, ragtime, and brass band traditions. The novel as a form evolved gradually from epistolary fiction, picaresque tales, and romance narratives. Shakespeare’s genius manifested in the scaffolding of Marlowe, Kyd, and the morality play tradition.

This is not merely an observation—it is a principle we use to authenticate historical claims. When something appears fully formed without precedent, we become suspicious. We look for missing links, lost evidence, or signs of fraud.

When Apparent Exceptions Occur

The law of gradual development is so reliable that when we encounter what appears to be an exception, we immediately seek explanations that preserve the underlying principle. History offers several categories of apparent exceptions, each with its own resolution:

The Genius Within Tradition

Sometimes an individual of extraordinary talent appears to make a quantum leap. But closer examination always reveals they were working within and extending an existing tradition. Mozart composed his first symphony at age eight—but he was born into a musical family, trained rigorously from age three, and worked within established Classical forms. He accelerated development but did not bypass it. Leonardo da Vinci’s innovations in painting and engineering built upon decades of Renaissance workshop practice and rediscovered classical knowledge. Even child prodigies require the raw materials of tradition.

The Lost Evidence

Sometimes we discover an advanced artifact or text that seems to lack predecessors—until archaeology or philology uncovers them. The sophistication of Minoan palace architecture at Knossos once seemed inexplicable until excavations revealed earlier Cretan settlements and continuous development. The mathematical sophistication of Babylonian astronomy seemed miraculous until cuneiform tablets revealed centuries of observational records. In these cases, the scaffolding was there all along; we simply hadn’t found it yet.

The Collective Oral Tradition

Some masterpieces emerge from oral cultures—the Homeric epics, the Vedas, the Epic of Gilgamesh. These appear to crystallize suddenly into written form. Yet these are explicitly products of multigenerational, communal development. The Iliad and Odyssey were orally composed over centuries by multiple bards before being transcribed in the 8th century BCE. Linguistic analysis reveals layers of composition, dialectical mixing, and formulaic structures typical of long oral evolution. They are not the work of a single voice or generation but the distilled wisdom of an entire tradition—anonymous, collective, and gradual.

The Retrospective Compilation

Sometimes a text appears more unified than its origins would suggest because later editors imposed coherence. The Bible reached its final form through centuries of redaction. The works attributed to Hippocrates represent a medical school’s collective output. Buddhist sutras were compiled long after the Buddha’s death. In these cases, apparent unity masks an evolutionary process obscured by editorial work.

These categories exhaust the normal explanations for apparent exceptions to gradual development. When we encounter something that seems to violate the law, we expect to find one of these resolutions. If we cannot, we face a genuine anomaly—something that demands explanation outside our normal framework.

Arabia’s Cultural Context: A Society Without Literary Infrastructure

To understand the anomaly we’re approaching, we must first establish what seventh-century Arabia actually was—and more importantly, what it was not.

The Arabian Peninsula in the 600s CE was a society organized around orality, kinship, and memory. Its people were not illiterate in the sense of being cognitively limited, but rather lived in a culture where writing played almost no role in the transmission of knowledge, art, or identity.

What Arabia Had

The Arabs possessed a sophisticated oral poetry tradition of remarkable complexity. Pre-Islamic poetry (the Mu’allaqat and related works) demonstrated linguistic virtuosity, elaborate metaphor, and strict metrical discipline. Poets memorized thousands of lines and competed in verbal tournaments. This was not a “primitive” culture but one that had invested its intellectual energy in auditory rather than visual forms of expression. Memory, not manuscripts, was the hard drive of culture.

What Arabia Lacked

But if we inventory the infrastructure of literate civilization—the apparatus that in other societies produced written masterworks—we find almost nothing:

- No schools or academies: There were no institutions dedicated to formal education, no madrasas or gymnasia where students learned to write extended prose. The Greco-Roman world had rhetorical schools for centuries; Arabia had none.

- No libraries or archives: There were no repositories of written knowledge, no equivalents to the Library of Alexandria or the archives of Nineveh. Books were not collected because books barely existed.

- No scribal class: Unlike Egypt with its hieroglyphic priesthood, Mesopotamia with its cuneiform scribes, or medieval Europe with its monastic copyists, Arabia had no professional class dedicated to writing. Scribes existed but were rare functionaries who recorded contracts, not composers of literature.

- No tradition of written prose: There were no Arabic histories, no philosophical treatises, no written legal codes, no theological texts, no scientific works, no epistolary literature. The entire genre of written prose simply did not exist in Arabic.

- No manuscript culture: There is no archaeological evidence of Arabic codices, scrolls, or book production before the Quran. Inscriptions exist—short texts on rocks, tombs, and monuments, typically in other languages or adapted scripts—but nothing resembling a literary manuscript.

The Arabic script itself was in a primitive state. Adapted from Nabataean Aramaic (itself derived from Aramaic, which came from Phoenician), the script lacked standardized vowel markings (tashkil), had ambiguous letter forms, and was used primarily for commercial notation. It was a merchant’s tool, not a medium for literary expression. The script’s ambiguities were so significant that early Quran manuscripts required someone who knew the oral recitation to accompany them—the written symbols alone were insufficient.

Comparative Context

To grasp how unusual this context is, consider what other civilizations possessed when they produced their great written works. For example, when Homer’s epics were transcribed in eighth-century BCE Greece, the culture already had centuries of Mycenaean palace administration behind it, continuous contact with Phoenician and Egyptian writing systems, an established epic oral tradition, and a growing merchant class that valued written records.

When Virgil composed the Aeneid in first-century BCE Rome, he worked within a thousand years of Latin literary development, drawing on extensive Greek cultural influence, established educational systems, public libraries, a literate elite class, and centuries of written history and oratory.

When the Vedas were finally written down around 500 BCE in India, they emerged from millennia of oral brahminical tradition, supported by established grammatical theory (Panini’s Ashtadhyayi), Sanskrit as a refined literary language, and a priestly class dedicated to textual preservation.

And when the Gospels were written in first-century Palestine, their authors participated in the literate Greco-Roman world, benefiting from established Jewish scribal traditions, extensive rabbinical textual commentary (midrash), Greek as a lingua franca with a millennium of written philosophy and history behind it, and ready access to papyrus and trained scribes.

Arabia had none of these preconditions. It was not on the verge of literacy; it was fundamentally organized around memory and speech.

The Economic Factor

It’s sometimes suggested that Mecca’s position as a trading hub would have naturally encouraged literacy. But trade literacy—marking goods, recording debts—is categorically different from literary composition. Medieval Europe had merchants who could write invoices but not essays. Phoenician traders spread their alphabet across the Mediterranean but produced almost no literature. Commercial writing and literary culture are distinct phenomena requiring different infrastructure.

The “Lost Literature” Hypothesis

Could there have been a sophisticated written tradition that simply vanished? This theory faces multiple problems.

First, the material evidence: Archaeology has recovered texts from far less favorable conditions. We have Egyptian papyri from the 3rd millennium BCE, Qumran scrolls preserved in desert caves, carbonized scrolls from Pompeii. The Arabian Peninsula has yielded ancient inscriptions in various languages, but no trace of pre-Islamic Arabic literary manuscripts. Not one fragment.

Second, the linguistic evidence: If a rich prose tradition had existed, it would have left linguistic sediment. When we trace the development of Arabic prose, we find that its grammar, rhetorical structures, and stylistic norms were all derived from the Quran, not applied to it. Classical Arabic grammar, as codified by scholars in Basra and Kufa in the 8th-9th centuries, extracted its rules from Quranic usage. This is the reverse of the normal pattern: usually, literary works conform to established grammatical norms that preexist them.

Third, the cultural memory: Arabs retained the reminiscence of the history of their oral poetry from the pre-Islamic period. They remembered the names of poets, the contents of their poems, the tribal genealogies, and historical contexts. Yet there is no memory, not even a legend, of earlier Arabic books or prose works. This absence is conspicuous. If such texts had existed and been lost, their memory would persist—as the lost works of Aristotle or Sappho persisted in Greek cultural memory.

The most parsimonious explanation is that extensive written Arabic literature before the Quran did not exist because the cultural infrastructure to produce it did not exist.

This is the context—a culture of memory, not manuscript; of recitation, not reading; of poetry, not prose—into which the Quran emerged.

Comparative Case: The New Testament’s Normal Development

To sharpen the contrast, consider a sacred text that follows the expected pattern of cultural evolution: the New Testament.

The Literate Context

The Gospels and Epistles emerged from the highly literate Greco-Roman world. By the first century CE, written Greek had been employed for literature, philosophy, history, and correspondence for nearly a millennium. The Mediterranean basin was saturated with texts: Homer, Plato, Aristotle, Herodotus, Thucydides, the playwrights, the orators. Public libraries existed in major cities. The educated elite were trained in rhetoric and composition from childhood.

Moreover, first-century Judaism had its own robust textual tradition. The Hebrew Bible had been written, redacted, and studied for centuries. The Septuagint (Greek translation of Hebrew scriptures) had existed for nearly three centuries. Rabbinical tradition involved detailed textual commentary (midrash). The Dead Sea Scrolls reveal a culture intensely focused on writing, copying, and interpreting texts.

Genre Continuity

The New Testament books fit recognizably into existing Greco-Roman genres. The Gospels resemble the bioi—biographical works about exemplary figures (lives of Socrates, Plutarch’s parallel lives, etc.). They follow Greco-Roman biographical conventions: birth narratives, public ministry, teachings, death, and legacy. The Epistles belong squarely to the ancient letter-writing tradition. Paul’s letters echo the rhetorical structures found in Seneca, Cicero, and the Stoic philosophers: greetings, thanksgiving, body argument, ethical exhortation, closing. The vocabulary and argumentative style reflect Hellenistic rhetorical education. The language itself—Koine Greek—was the sophisticated product of centuries of linguistic evolution, the lingua franca of an interconnected empire with established rules for written prose.

Evolutionary Development

The New Testament books were composed over roughly 50-70 years by multiple authors in different locations, drawing on oral traditions, written sources (the “Q source” and other materials), and earlier texts. The Gospels show clear literary dependence—Mark influencing Matthew and Luke—demonstrating a process of textual evolution and redaction. Later books incorporate and refine earlier ideas.

The Pattern

The New Testament represents cultural continuity—faith expressed through the sophisticated textual apparatus of an already literate civilization. It is what we would expect: religious innovation working within and through existing literary forms, composed by members of a culture that had been writing books for a thousand years.

The Quran, by contrast, represents cultural discontinuity—a complete, sophisticated book emerging from a culture that had not yet developed the infrastructure for producing books. One grows from a library; the other builds one.

The Sudden Emergence: Literary Dimensions

In this context of oral culture and rudimentary writing, the Quran appeared not as a tentative first step toward literacy, but as a fully realized written work that redefined what Arabic could be.

A Self-Conscious Book

The Quran repeatedly refers to itself as a kitāb (book), using a term that was understood but not produced in pre-Islamic Arabia. It is not a collection of orally transmitted wisdom later transcribed; it presents itself as a written text from the beginning, demanding to be read, preserved, and transmitted in written form. This self-consciousness about its textual nature is itself unusual for a culture that had no precedent of publishing books.

Genre Innovation

The Quran’s form defied existing Arabic categories. Pre-Islamic Arabs distinguished clearly between shi’r (metered poetry with strict prosodic rules) and nathr (prose, which barely existed in literary form). The Quran is neither. It possesses rhythmic and phonetic patterns but does not conform to any of the traditional buḥūr (metrical forms) of Arabic poetry. It exhibits saj’ (rhymed prose) but in a more complex and varied way than the simple saj’ of pre-Islamic oracles and speeches.

Early Muslims called it simply “Quran” (recitation), implicitly acknowledging that existing genre categories could not contain it. Contemporary opponents of Muhammad accused him of being a poet, but they knew he was not—his language did not scan according to poetic meters. They accused him of being a soothsayer, but his language was more complex than a kāhin’s utterances. The Quran invented its own category.

Linguistic Sophistication

While aesthetic judgments are subjective, certain formal features can be objectively analyzed:

- Vocabulary richness: The Quran employs approximately 77,000 words from a root vocabulary of around 1,800 roots, creating an extraordinarily dense semantic network. Words are deployed with precision and consistency across 114 chapters revealed over 23 years.

- Phonetic patterning: The Quran exhibits complex patterns of assonance, consonance, and internal rhyme that extend beyond simple end-rhyme. Verses often conclude with phonetically related words (fawāṣil) that create rhythmic coherence while avoiding the mechanical predictability of strict meter.

- Structural variation: The chapters vary dramatically in length, tone, and rhetorical strategy—from the short, apocalyptic early Meccan suras to the long, legislative Medinan ones—yet maintain linguistic consistency and recognizable style throughout.

- Syntactic complexity: The Quran employs sophisticated Arabic grammatical structures, including rare forms and constructions that became models for later linguistic analysis. Its use of ellipsis, embedding, and syntactic parallelism created patterns that grammarians later codified as normative.

Contemporary Testimony

Even the Quran’s opponents acknowledged its distinctiveness. They questioned the ability of its said author in producing such a Quran, insinuating that he got help from others who did not know Arabic. However, the Quran was written in perfect Arabic tongue.

We are fully aware that they say, “A human being is teaching him!” The tongue of the source they hint at is non-Arabic, and this is a perfect Arabic tongue. (16:103)

The Quran openly challenged the contemporaries of its time to produce a work similar to it. If the Quran was not unique, such a challenge would have easily been acted upon by the opponents at that time.

If they say, “He fabricated it,” say, “Then produce one sura like these, and invite whomever you wish, other than GOD, if you are truthful.” (Quran 10:38)

This challenge assumes a shared recognition that the text possesses distinctive qualities that cannot be easily reproduced—a claim that would have been immediately dismissed as absurd if contemporaries had regarded it as unremarkable.

Manuscript Evidence

The earliest extant Quran manuscripts—including the Samarkand Kufic Quran, the Qur’ān of ʿUthmān, and the Topkapi manuscript date to shortly after the Prophet’s death, while the Birmingham manuscript corresponds to the life of the Prophet; all show remarkable textual stability. While minor orthographic variations exist (reflecting the early script’s ambiguities), the textual content is consistent. This suggests the text achieved fixed written form very early, contradicting theories of gradual textual evolution over generations.

The Sudden Emergence: Mathematical Dimensions

If the Quran’s literary form alone seemed anomalous, its numerical structure presents a separate puzzle—one that could not have been engineered by its original audience and was not discovered by them.

Consider these verifiable word counts in the Quranic text:

- The word “day” (yawm) in its singular form appears 365 times—matching the number of days in a solar year.

- The word “month” (shahr) appears 12 times—matching the number of months in a year.

- The word “days” (ayyām) in its plural form appears 30 times—corresponding to the average number of days in a month.

- More remarkably: if one counts from the first mention of “month” (shahr) in 2:185 to its final mention in 97:3, the word “day” (yawm) appears exactly 354 times in that range—precisely the number of days in a lunar year.

These are not numerological interpretations or symbolic readings. They are simple frequency counts of ordinary Arabic words that can be verified by anyone with a concordance. Yet they correspond precisely to astronomical and calendrical cycles—the rhythms by which humanity measures time.

Other patterns compound the puzzle:

- “Man” (insān, bashar) and “angel” (malāʾika) each appear 88 times.

- “This world” (dunyā) and “the hereafter” (ākhira) each appear 115 times.

- “Devil” (shayṭān) and “angel” (malak) both appear 88 times.

- “Life” (ḥayāt) and “death” (mawt) both appear 145 times.

Code 19: The Disjointed Letters

But the numerical architecture of the Quran extends beyond simple word counts. Twenty-nine chapters begin with mysterious letter combinations known in Arabic as al-muqaṭṭaʿāt, or “disjointed letters.” These appear as seemingly random sequences: Alif Lām Mīm (الم), Ḥā Mīm (حم), Ṭā Hā (طه), Yā Sīn (يس). The letters are pronounced individually and carry no direct lexical meaning in Arabic. For over a millennium, traditional commentators could only say, “God knows best what they mean.”

Modern computational analysis, however, has revealed that these initials follow precise mathematical patterns. Within each of the fourteen different sets where they occur, the letters appear in frequencies divisible by 19—a number the Quran itself highlights as significant: “Over it is nineteen” (74:30), followed by verses describing this as “one of the great miracles” and a “warning to the human race. (74:35-36)”

The precision is striking. The letter Qāf (ق) appears in both Sura 42 and Sura 50 exactly 57 times each (19 × 3), despite Sura 42 being twice as long as Sura 50. The letters Ḥā Mīm (حم) across Suras 40-46 appear 2,147 times total (19 × 113). The letters Yā Sīn (يس) in Sura 36 occur 285 times (19 × 15). These are not approximate correlations or patterns imposed through selective counting—they are exact multiples verifiable through straightforward frequency analysis.

The Quran itself appears to signal the significance of these letters. Immediately after presenting them, verses often declare: “A. L. R. These are the verses of the profound scripture” (12:1), or “T. S. M. These are proofs of this clarifying scripture” (26:1-2). The phrasing suggests the letters themselves constitute evidence of the author’s deliberate placement as part of the mathematical structure of the text.

Systematic Refutation: Why Standard Explanations Fail

We have established the anomaly: a sophisticated written text that was also mathematically structured, emerging from a culture without the preconditions for producing such texts. Now we must rigorously examine whether any of the standard explanations for apparent exceptions to gradual development can account for this case.

Work of Muhammad and Others

The Claim: Muhammad or his scribes have intentionally arranged the text to produce these patterns?

Why It Fails:

First, no concordances existed. The technology for systematically counting word frequencies did not exist in the 7th century. There were no indexes, no alphabetized references, no means of tracking word occurrences across a text of 77,000 words. Even if someone had wanted to count every occurrence of “day” across 114 chapters, the task would have been monumentally difficult without modern tools.

Second, no evidence of awareness. There is no record—not in hadith, not in early tafsir (commentary), not in biographical accounts—that Muhammad or his companions were aware of these numerical patterns or attempted to create them. The patterns were discovered only after the development of Quranic concordances and, in modern times, computational text analysis.

Third, the constraints would be paralyzing. Composing a text while simultaneously tracking letter and word frequencies across multiple categories would require extraordinary mental capacity. To adjust the 354th occurrence of “day” to fall exactly between the first and last mentions of “month” while also maintaining the total count of “day” at 365 and the corresponding letter counts, while simultaneously composing coherent Arabic prose on theological and legal matters, while maintaining stylistic consistency—this seems beyond human cognitive capacity even today with our all our access to technology let alone in 7th century Arabia.

Fourth, the patterns serve no apparent rhetorical purpose. These numerical structures do nothing to advance the Quran’s message, persuade its audience, or clarify its teachings. They were invisible to their original audience and remained so for centuries. If they were consciously designed, they were designed to be discovered only by future generations with different analytical tools—an extraordinary anticipation.

The Editing Hypothesis

The Claim: Later editors have adjusted the text to impose these patterns.

Why it Fails:

When we study the oldest manuscripts of the Quran, we find that the text shows remarkable stability from the earliest manuscripts onward, with variations only in minor orthographic details, not word content or order. If one were to do a side-by-side comparison of the oldest manuscripts with the Quran script we have today, we find that the consonantal script has not deviated.

Additionally, there is another major hurdle. The editors would have needed to be aware of the numerical patterns to impose them, but as noted, there is no evidence that anyone knew these patterns existed until modern times. The patterns involve letter frequencies, which are even more difficult to manipulate without disrupting meaning than word counts. Changing a single word affects multiple letter counts simultaneously.

The patterns appear to have been there from the beginning, embedded in a text whose first audience had no means to detect them and whose preservation tradition would have prevented their later insertion.

The Genius Within Tradition

The Claim: Muhammad was simply a literary genius who, like Mozart or Shakespeare, achieved within existing forms what others could not.

Why It Fails:

Geniuses work within and extend traditions; they do not create traditions ex nihilo. Mozart’s genius manifested in symphonies, concertos, and operas—forms that already existed. Shakespeare wrote in established genres (tragedy, comedy, history play) using iambic pentameter—a metric tradition inherited from earlier English poets. Their genius was in perfecting existing forms, not inventing entirely new ones. Additionally, each of these individuals has a body of work showing their progression as well as a rich history of predecessors that they could build upon.

Muhammad does not fit this mold because he possessed

- No formal education

- No previous work showing a progression in his literary abilities

- No earlier work from others to rely upon in the field

- No indication of access to abstract mathematical concepts

- No known history of others in his region utilizing applied mathematics

- No account of other books embedding mathematical structures into literary works

This is not genius within tradition—it is the creation of the text that, for all intents and purposes, should not exist for its time and place. It is as if Mozart’s first composition had been the symphony as a perfected form, before anyone had written simpler pieces, when instrumental music itself barely existed.

Lost Evidence of Precursors

The Claim: A sophisticated Arabic literary tradition existed but was lost—destroyed, forgotten, or buried beneath the sands.

Why It Fails:

Material archaeology: The Arabian Peninsula has been extensively excavated. We have found ancient South Arabian inscriptions, Nabataean texts, even Greek and Latin inscriptions from the region. We have recovered documents from far less promising conditions—papyri from Egypt’s desert sands, scrolls from Qumran’s caves, cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamian ruins. If a substantial corpus of Arabic literary manuscripts had existed, some trace would remain. None has been found.

Linguistic paleontology: Languages preserve evidence of their literary history. We can trace the evolution of Greek prose from Herodotus to Thucydides to Plato by examining changing vocabulary, syntax, and stylistic conventions. We can observe Latin evolving from Cicero to Tacitus to Augustine. But when we examine Arabic, we find that classical prose norms were derived from the Quran, not applied to it. There is no linguistic evidence of earlier models from which Quranic Arabic evolved. The first comprehensive Arabic dictionaries and grammars (8th-9th centuries) used the Quran as their primary reference text—because there was no earlier corpus to reference.

Cultural memory: Pre-Islamic Arabs were obsessive preservers of oral tradition. They memorized elaborate genealogies stretching back generations. They preserved poetry from the Jahiliyyah (pre-Islamic period) and remembered the names of poets, the occasions of poems, the tribal contexts. Yet there exists no memory—not even a legend—of pre-Islamic Arabic books or written literature. If such texts had existed and been lost, their memory would have persisted in oral tradition, as the lost works of Sappho or Aristotle persisted in Greek cultural memory. The silence is complete.

Occam’s Razor: The simplest explanation for the absence of evidence is absence of the thing itself. The precursors did not exist because the cultural infrastructure to produce them did not exist.

Collective Oral Evolution

The Claim: Like Homer’s epics or the Vedas, the Quran evolved gradually through oral tradition before being written down, creating the appearance of sudden emergence.

Why It Fails:

Single voice, single generation: The Quran was delivered by one person over 23 years. The text itself presents it as the utterances of Muhammad during his prophetic career (610-632 CE), which wasn’t even disputed by his contemporaries, let alone modern scholarship. This is radically different from the Homeric epics, which were composed orally over centuries by multiple bards and show clear signs of layered composition. Linguistic analysis of Homer reveals different dialectical strata, formulaic phrases characteristic of oral composition, and narrative inconsistencies typical of multi-generational development.

The Quran shows none of these features. Its vocabulary and style remain consistent across early Meccan suras and late Medinan ones. While themes and legal content evolve with circumstances, the linguistic register does not. It reads as the product of a single voice, not a gradually evolved tradition.

Written from the beginning: The Quran’s self-reference as a “book” and the early fixation of its text in manuscript form demonstrate it was conceived as a written work from the start, not an oral tradition later transcribed. The earliest manuscripts date within decades of Muhammad’s death, and the community’s concern with textual preservation indicates this was not a case of oral tradition being belatedly captured in writing.

No evidence of evolution: We have oral tradition from Muhammad’s contemporaries, including pre-Islamic poetry. We can compare oral and written forms. The Quran does not exhibit the characteristic markers of evolved oral composition that we see in genuinely oral works.

Retrospective Compilation and Editing

The Claim: The Quran achieved its apparent unity and sophistication through later editorial work—perhaps over generations, as happened with other religious texts like the Hebrew Bible.

Why It Fails:

Early manuscript evidence: The earliest Quran manuscripts—including the Birmingham manuscript (dated to 568-645 CE) and others from the first Islamic century—show remarkable textual consistency with the received text. While early Arabic orthography had ambiguities, the actual word content is stable. This is inconsistent with gradual editorial evolution.

Living memory: Unlike texts compiled centuries after their sources (like the Hebrew Bible or Buddhist sutras), the Quran was written down during the prophet’s life, memorized by the masses, and also by each subsequent generation. Any significant editorial changes would have been detectable in the recorded manuscripts found in various time periods and regions, which do not show any sign of this.

The numerical patterns: If editors were responsible for the Quran’s final form, they would have needed to be aware of the numerical patterns to create them—yet there is no evidence anyone knew these patterns existed until modern times, long after the text was fixed. The patterns would have had to emerge accidentally from editorial work, which seems implausible given their precision.

Exaggeration of Uniqueness

The Claim: The Quran is not actually as unique or sophisticated as claimed. Its distinctiveness is exaggerated by believers and by cultural distance that makes evaluation difficult.

Why It Fails:

Contemporary testimony: The Quran’s distinctiveness was acknowledged by its contemporaries—including opponents. If it were merely competent Arabic prose or conventional poetry, Muhammad’s opponents could have easily dismissed it. Instead, they struggled to categorize it and, according to Islamic sources, some refused to listen to it for fear of being persuaded by its eloquence. This suggests even hostile contemporaries recognized its distinctive qualities.

Linguistic analysis: Modern Arabic linguists, including secular scholars, consistently note the Quran’s distinctive style. Its departure from both poetry and prose conventions is not a matter of religious interpretation but of formal linguistic analysis. It created patterns that became normative for Arabic prose precisely because there were no earlier models.

Historical impact: The Quran’s influence on Arabic language and literature is comparable to Homer’s on Greek or Shakespeare’s on English—it defined the standard. This level of influence is difficult to achieve with merely competent or derivative work.

The numerical patterns: Whatever one makes of the literary qualities (which involve some subjective judgment), the mathematical patterns are objectively verifiable and cannot be dismissed as exaggeration. This includes both the frequency of words in connection with celestial phenomena and the more advanced structure, which is based on the number 19.

Comparative context: When we compare the Quran to actual examples of early, primitive prose in other languages—the first halting attempts at written narrative or argument—the contrast is stark. Early written works typically show awkwardness, inconsistency, and limited vocabulary. The Quran exhibits none of these characteristics.

The Explanatory Gap

Each standard explanation, when examined rigorously, fails to account for the Quran’s emergence. We are left with an anomaly that resists conventional historical explanation: a sophisticated written work appearing in a culture without the prerequisites for producing such work, exhibiting literary qualities and numerical patterns its original audience could not have deliberately engineered, and achieving textual stability from the earliest manuscripts onward.

The gap between what the historical context would predict and what actually appeared remains unbridged.

The Anomaly Stands

We return to our opening image: the Great Pyramid standing alone on the plateau with no mastabas, no prototypes, no scaffolding—only the finished monument, perfect from the beginning.

This is not merely a provocative metaphor. It is a precise analogy to what the historical record shows regarding the Quran:

- A culture with no tradition of written books produces a book

- A society with rudimentary script produces linguistically sophisticated prose

- An oral culture produces a self-conscious written text

- An environment without literary infrastructure produces a work that defines literary standards

- A context lacking the tools for mathematical encoding produces a text with precise numerical structures

- The first Arabic book from this region is also the most preserved, most memorized, and most influential book in the history of the world

Each of these facts, individually, might be explained away. Together, they form a pattern that exceeds the reach of our normal explanatory framework.

The secular historian can document the anomaly but struggles to explain it. Standard historical explanations—genius, lost evidence, oral evolution, editorial development, exaggeration—all fail when tested against the specific conditions of seventh-century Arabia and the specific characteristics of the Quranic text.

For the believer, this points naturally toward transcendence: a divine text descending into an unlettered world, bringing both message and medium at once. The scaffolding is invisible because it is vertical rather than horizontal—divine rather than human.

For the secular observer, the anomaly poses a subtler question: how does a society produce what it has not yet evolved the capacity to create? How does complexity emerge without precursors? How does a civilization build a monument before it has learned to quarry stone?

Conclusion: Where History Folds

Human culture is an architecture of continuity. We learn by imitation, refine by failure, and build by inheritance. The trajectory from simple to complex, from crude to sophisticated, from prototype to masterpiece holds across every domain of human achievement. This is not merely an observation—it is the principle by which we understand cultural evolution and authenticate historical claims.

Yet the Quran stands as an exception that resists explanation. The normal scaffolding of cultural development—the failed experiments, the crude prototypes, the gradual refinement—is entirely absent. The first published book of Arabia appears not as a beginning but as a culmination, not as an experiment but as a standard, not as a stepping stone but as a destination.

We are left with three possible positions:

First, one might maintain that despite the absence of evidence, precursors must have existed—that the scaffolding was there but has been lost to history. This requires believing that Arabia possessed a sophisticated literary tradition that left no material trace, no linguistic residue, no cultural memory, and no archaeological footprint, despite preservation conditions that have yielded texts from far older and more fragile origins. This position preserves the law of gradual development but only through unfalsifiable speculation.

Second, one might accept the historical anomaly but suspend judgment on its explanation—acknowledging that something extraordinary occurred without committing to a specific cause. This is the position of intellectual honesty in the face of insufficient explanatory frameworks. It admits that our normal tools of historical analysis encounter their limit here, that the Quran represents a genuine puzzle that neither standard religious nor standard secular explanations adequately resolve.

Third, one might interpret the anomaly as evidence of transcendent origin—that the Quran’s appearance violates the laws of cultural development precisely because it originates outside the normal process of cultural development. From this perspective, the missing scaffolding is not a historical mystery but a theological statement: the text announces its own origin in its very impossibility.

In seventh-century Arabia, in a culture of memory and recitation, of campfire poetry and merchant tallies, something appeared that should not have been possible according to the normal laws of cultural evolution. It appeared not tentatively but completely, not roughly but refined, not as a beginning but as a perfection.

The monument stands without its scaffolding. The pyramid rises from sand with no trace of the stones that should have taught its builders how to build. And the question remains suspended in the desert air: How did a culture with no history of writing books or mathematical sophistication produce the most influential, most mass memorized, and most mathematically structured book in the history of the world?

Whether one interprets this as revelation or revolution, miracle or mystery, the fact of the anomaly persists. The Quran stands where history folds back on itself—a beginning that looks like an ending, a foundation that resembles a summit, a first step that possesses the sophistication of a final achievement.

What remains undeniable, regardless of one’s metaphysical commitments, is that the Quran occupies a unique space in human history. It is a monument that appears fully formed, a structure whose foundations remain invisible to historical investigation, a text that creates rather than reflects the literary tradition from which it supposedly emerged.

Related Content:

- https://www.masjidtucson.org/quran/appendices/appendix1.html

- https://qurantalk.gitbook.io/quran-initial-count