When scholars of Christianity speak of high and low Christology, they are not referring to two different religions but to a spectrum of belief regarding the status of Christ. Some traditions elevate him to pre-existent divinity, while others see him primarily as a prophet and teacher. The same framework can help us think about the history of Islamic jurisprudence.

Within Sunni Islam, the relationship between the Quran and the Hadith has never been a simple binary of “accept or reject.” Instead, it developed across a spectrum of authority, ranging from those who treated Hadith as a useful but non-binding reference to those who elevated it as a supreme authority that overrides the Quran itself.

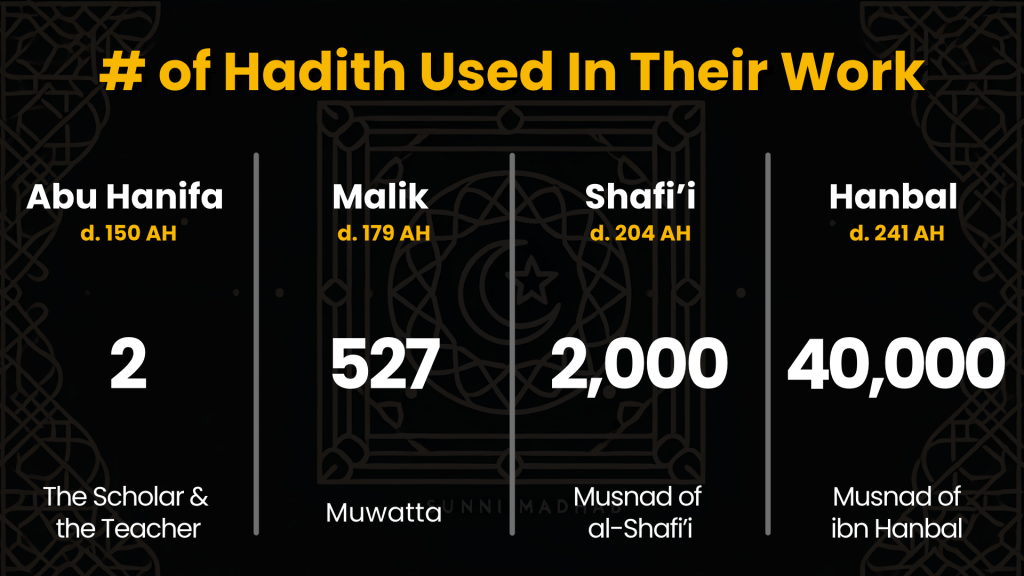

To describe this range, we can borrow the same language of “high” and “low” and speak of Hadithology—the study of how different schools of thought understood the role and authority of Hadith. On this spectrum, Abū Ḥanīfa occupies the “low” end, treating Hadith with caution and prioritizing the Quran and reason. Mālik sits at a moderate level, granting Hadith authority but not absoluteness. Al-Shāfiʿī pushed it further, making Hadith a secondary form of revelation alongside the Quran. And Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal took the “high” position, placing Hadith and Sunnah so far above that they could dictate how even the Quran itself was to be read.

This ladder of Hadithology reveals that what many Muslims assume to be a monolithic approach was, in fact, contested from the beginning. And the implications are far from academic: whether one embraces a low or high Hadithology radically changes the balance of authority between human reports and God’s revelation.

What is Hadithology?

Hadithology, as I use the term, refers to the way a school of thought positions hadith in relation to the Quran and to reason. It is not about the science of hadith authenticity (ʿilm al-ḥadīth), but about the status given to hadith once accepted as genuine. Do hadith merely inform practice? Do they carry binding authority? Do they supplement Quran as a second form of revelation? Or do they reign supreme over all other sources?

This question was never peripheral. The Quran calls itself a “fully detailed” scripture (6:114) and “the best hadith” (39:23). Yet as hadith literature expanded in circulation, proto-Sunni scholars faced the challenge of reconciling these Quranic claims with the massive body of reports attributed to the Prophet. The four Sunni imams answered that challenge in very different ways.

By speaking of Hadithology, we are giving a name to this spectrum. Just as Christology studies views of Christ, Hadithology studies views of hadith’s authority. It allows us to map out how the earliest jurists positioned themselves: from Abū Ḥanīfa’s caution, to Mālik’s balance, to Shāfiʿī’s elevation, and finally to Ibn Ḥanbal’s exaltation of hadith over Quran.

Low Hadithology — Abū Ḥanīfa

Abū Ḥanīfa (d. 767), founder of the Ḥanafī school, represents the low end of Hadithology. His approach to hadith was cautious, pragmatic, and always subordinate to higher sources of authority—namely the Quran and reason.

For Abū Ḥanīfa, a hadith could inform practice, but it did not carry binding force in itself. Reports were to be weighed carefully, and if they conflicted with the Quran or with established rational principles, they could be set aside. In his method, qiyās (analogy) and ra’y (reasoned judgment) carried more weight than hadith. This did not mean he rejected the Prophet’s teachings; it meant he refused to treat every transmitted report as if it were divine legislation.

This approach reflects an instinct to protect the primacy of the Quran. The Quran was the unquestioned foundation, and reason was the God-given tool for extending its principles into new cases. Hadith could supplement this process, but it could never serve as a secondary source of religious law beside the Quran or override the Quran.

The result was a jurisprudence that, while eventually rebranded as Sunni, originally kept its independence from the vast contradictory corpus of reports. In the ladder of Hadithology, Abū Ḥanīfa’s school is the closest to saying: Hadith is not regarded with any level of legislative authority.

Despite later generations of Sunnis attempting to rebrand Abu Hanifa as a staunch upholder of Hadith and Sunni orthodoxy, based on how he was viewed by proto-Sunnis it is clear that their despisement towards him was that he did not take from Hadith. As Ibn Qutayba (d. 276/889) explains, they loathed Abu Hanifa because he rejected the rulings found in Hadith.

“We do not loathe (lā nanqimu) Abū Hanı̄fa because he employs speculative jurisprudence, for all of us to do this (kullunā yarā). However, we loathe him because when a hadı̄th comes to him on the authority of the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, he opposes it (yukhālifuhu) in preference for something else.“1

Moderate Hadithology — Mālik

Mālik ibn Anas (d. 795), founder of the Mālikī school, represents the moderate tier of Hadithology. Unlike Abū Ḥanīfa, Mālik granted hadith a stronger level of authority, but he did not treat every report as binding in all circumstances. His balance came from giving special weight to the living tradition of Medina—the ʿamal ahl al-Madīna (practice of the people of Medina).

For Mālik, the consensus and practice of Medina’s community carried an authority that could even outweigh hadith reports. His reasoning was straightforward: the Prophet lived in Medina, his companions practiced Islam there, and the later communities preserved that practice. If a report contradicted the living tradition of Medina, then the report, not the community’s practice, was suspect.

This approach placed hadith in a middle ground. They were not easily dismissed as in Abū Ḥanīfa’s method, but neither did they reign unchecked. The authority of hadith was filtered through the lens of communal practice, a check against treating every report as an isolated command.

In the ladder of Hadithology, Mālik’s position shows a movement upward—hadith are authoritative, but they must be interpreted within the framework of the Prophet’s community life.

Elevated Hadithology — al-Shāfiʿī

Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī (d. 820) marks a turning point in Hadithology. While Abū Ḥanīfa discarded the binding force of hadith and Mālik balanced them against communal practice, al-Shāfiʿī elevated hadith to a new status: secondary revelation.

Al-Shāfiʿī systematized the emerging science of uṣūl al-fiqh (principles of jurisprudence), and in doing so, he anchored hadith alongside the Quran as binding textual sources. To him, the Sunnah was inseparable from revelation itself. If the Quran was divine speech, then authentic hadith were divine explanation. Rejecting hadith meant rejecting revelation.

Yet even in this elevation, al-Shāfiʿī placed one boundary: hadith could never abrogate or cancel the Quran. The Quran retained final supremacy. Still, this was a decisive shift—hadith were no longer consultative or contextualized; they were binding evidence in their own right. As stated in his Risalah (127):

“God stated to them that He only abrogates things in the Book by means of the Book, and that Prophetic Practice does not abrogate the Book. It is instead subordinate to the Book, containing the like of what is revealed in the form of a clear text, and explaining the meaning of what God revealed in general terms.”

The implications of al-Shāfiʿī’s project were massive. He created the intellectual framework that made hadith indispensable to Sunni legal theory. In the spectrum of Hadithology, his position represents the elevation of hadith into the very category of revelation, subordinate only to the Qur’an itself.

High Hadithology — Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal

Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal (d. 855) occupies the high end of Hadithology, pushing the authority of hadith to its furthest extent. For him, the Sunnah preserved in hadith was not only binding but could even rule over the Quran. Reports were the master key through which the Quran had to be interpreted, and could override the plain meaning of the Quran itself.

Where Abū Ḥanīfa would exercise caution, and Mālik would balance reports against communal practice, and al-Shāfiʿī would limit hadith to a secondary but subordinate revelation, Ibn Ḥanbal took the most maximalist stance: hadith were to be accepted, trusted, and applied even when reason or Quranic wording seemed to resist them.

His famous devotion to collecting and preserving hadith—culminating in the Musnad, a collection of some 40,000 reports—shows this commitment. In matters of law, creed, and practice, Ibn Ḥanbal gave hadith an unchecked authority. Weak reports should be preferred to rational inference, and theological disputes were settled not by argument but by citation of transmitted sayings.

At this height of Hadithology, the Quran was no longer the uncontested foundation but became dependent on hadith for its meaning and application. Ibn Ḥanbal’s stance paved the way for a hadith-centered orthodoxy that would dominate much of Sunni thought thereafter.

In the book “Misquoting Muhammad,” Jonathan Brown writes on page 44,

“Although Ibn Hanbal acknowledged that there were many Hadiths in his Musnad that suffered from some flaw or weakness in their Isnads, he felt they were all admissible in elaborating some area of the Shariah. He explained that, as long as a Hadith was supported by an Isnad reliable enough to show it was not a patent forgery, “then one was required to accept it and act accordingly to the Prophet’s words.’ ‘A flawed Hadith is preferable to me than a scholar’s opinion or Qiyas,’ he added. Muslims were, Ibn Hanbal reminded his students, commanded to take their religion from on high and not rely on the flawed faculty of reason.”

For Hanbal, the purity of faith rested on unwavering adherence to the Hadith and Sunnah, which he considered the ultimate authority in understanding matters of religion. From this Ḥanbali high-hadithology mindset came such maxims attributed to figures like “Sa’id ibn Mansur narrated on the authority of ‘Isa ibn Yunus on the authority of al-Awza’i on the authority of Makhul, who said:

“The Quran needs the Sunnah more than the Sunnah needs the Quran.”

The same statement was related by al-Awza’i on the authority of Yahya ibn Abi Kathir, who was also reported to have said,

“The Sunnah came to rule over the Qur’ān, it is not the Qur’ān that rules over the Sunnah.“

Final Thoughts

Placed side by side, the four Sunni imams reveal a striking progression in how hadith were valued. Abū Ḥanīfa represents the lowest point on the spectrum, where hadith were at best considered but never binding—Quran and reason held the real authority. Mālik raised their status, giving them authority but still subjecting them to the living practice of Medina. Shāfiʿī then pushed further, canonizing hadith as a form of secondary revelation that had to be obeyed, though still subordinate to the Quran. Finally, Ibn Ḥanbal took the spectrum to its highest point: hadith supremacy, where reports governed not only law but the very way the Qur’an itself was to be read.

This spectrum of Hadithology makes one thing clear: what later became “orthodoxy” was not inevitable. The dominance of a high Hadithology—where hadith rule over the Quran—was the result of historical choices, not divine decree. The early jurists offered a range of models, from cautious Quran-centered reasoning to uncompromising hadith-centered literalism.

Related Articles: