A common maxim about the Hadith corpus is: for every Hadith, there is an equal and opposite Hadith. This reflects the reality that many individuals fabricated Hadith to support conflicting political or theological positions. The result is a vast, often contradictory body of literature—pro-Aisha Hadith, anti-Aisha Hadith; pro-Umayyad, anti-Umayyad; pro-Ali, anti-Ali—and this extends to core doctrinal debates as well.

One particularly fascinating subset is what may be called anti-Hadith Hadith—reports that, if taken as authentic, undermine the legitimacy of the Hadith corpus itself. Even more curious is the existence of anti-Quran-alone Hadith—a smaller collection of reports aimed at preemptively condemning those who would later argue for following the Quran as the sole source of Islamic law.

One of the most cited examples of this genre appears in both Sunan Ibn Majah and Sunan Abi Dawud. In these narrations, the Prophet is depicted warning against individuals who say the Quran alone is sufficient:

Miqdam bin Ma’dikarib Al-Kindi narrated that: The Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) said: “Soon there will come a time that a man will be reclining on his pillow, and when one of my Ahadith is narrated he will say: ‘The Book of Allah is (sufficient) between us and you. Whatever it states is permissible, we will take as permissible, and whatever it states is forbidden, we will take as forbidden.’ Verily, whatever the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) has forbidden is like that which Allah has forbidden.”

حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو بَكْرِ بْنُ أَبِي شَيْبَةَ، حَدَّثَنَا زَيْدُ بْنُ الْحُبَابِ، عَنْ مُعَاوِيَةَ بْنِ صَالِحٍ، حَدَّثَنِي الْحَسَنُ بْنُ جَابِرٍ، عَنِ الْمِقْدَامِ بْنِ مَعْدِيكَرِبَ الْكِنْدِيِّ، أَنَّ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ ـ صلى الله عليه وسلم ـ قَالَ “ يُوشِكُ الرَّجُلُ مُتَّكِئًا عَلَى أَرِيكَتِهِ يُحَدَّثُ بِحَدِيثٍ مِنْ حَدِيثِي فَيَقُولُ بَيْنَنَا وَبَيْنَكُمْ كِتَابُ اللَّهِ عَزَّ وَجَلَّ فَمَا وَجَدْنَا فِيهِ مِنْ حَلاَلٍ اسْتَحْلَلْنَاهُ وَمَا وَجَدْنَا فِيهِ مِنْ حَرَامٍ حَرَّمْنَاهُ . أَلاَ وَإِنَّ مَا حَرَّمَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ ـ صلى الله عليه وسلم ـ مِثْلُ مَا حَرَّمَ اللَّهُ ” .

Sunan Ibn Majah 12

https://sunnah.com/ibnmajah:12

حَدَّثَنَا عَبْدُ الْوَهَّابِ بْنُ نَجْدَةَ، حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو عَمْرِو بْنُ كَثِيرِ بْنِ دِينَارٍ، عَنْ حَرِيزِ بْنِ عُثْمَانَ، عَنْ عَبْدِ الرَّحْمَنِ بْنِ أَبِي عَوْفٍ، عَنِ الْمِقْدَامِ بْنِ مَعْدِيكَرِبَ، عَنْ رَسُولِ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم أَنَّهُ قَالَ “ أَلاَ إِنِّي أُوتِيتُ الْكِتَابَ وَمِثْلَهُ مَعَهُ أَلاَ يُوشِكُ رَجُلٌ شَبْعَانُ عَلَى أَرِيكَتِهِ يَقُولُ عَلَيْكُمْ بِهَذَا الْقُرْآنِ فَمَا وَجَدْتُمْ فِيهِ مِنْ حَلاَلٍ فَأَحِلُّوهُ وَمَا وَجَدْتُمْ فِيهِ مِنْ حَرَامٍ فَحَرِّمُوهُ أَلاَ لاَ يَحِلُّ لَكُمْ لَحْمُ الْحِمَارِ الأَهْلِيِّ وَلاَ كُلُّ ذِي نَابٍ مِنَ السَّبُعِ وَلاَ لُقَطَةُ مُعَاهِدٍ إِلاَّ أَنْ يَسْتَغْنِيَ عَنْهَا صَاحِبُهَا وَمَنْ نَزَلَ بِقَوْمٍ فَعَلَيْهِمْ أَنْ يَقْرُوهُ فَإِنْ لَمْ يَقْرُوهُ فَلَهُ أَنْ يُعْقِبَهُمْ بِمِثْلِ قِرَاهُ ” .

Narrated Al-Miqdam ibn Ma’dikarib: The Prophet (ﷺ) said: Beware! I have been given the Qur’an and something like it, yet the time is coming when a man replete on his couch will say: Keep to the Qur’an; what you find in it to be permissible treat as permissible, and what you find in it to be prohibited treat as prohibited. Beware! The domestic ass, beasts of prey with fangs, a find belonging to confederate, unless its owner does not want it, are not permissible to you If anyone comes to some people, they must entertain him, but if they do not, he has a right to mulct them to an amount equivalent to his entertainment.

Sunan Abi Dawud 4604

https://sunnah.com/abudawud:4604

These Hadith place the Prophet in direct opposition to those who uphold the Quran alone and reject the binding authority of Hadith or Sunnah. But this narrative becomes especially problematic when compared to early historical reports attributed to the Prophet’s closest companions.

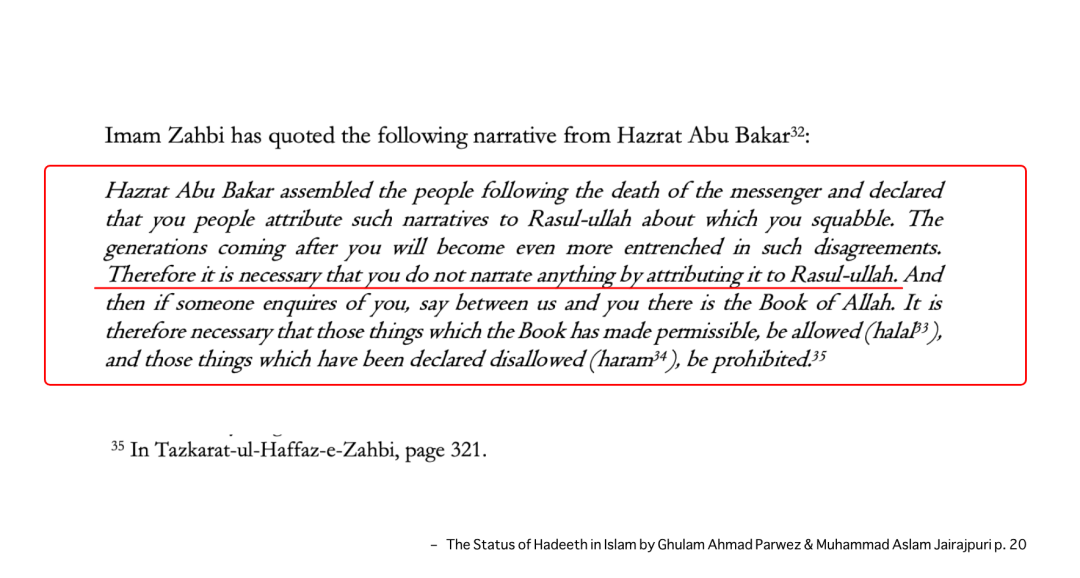

Consider a striking statement attributed to Abū Bakr after the Prophet’s death, as recorded by al-Dhahabī in Tadhkirat al-Ḥuffāẓ (1/9), through a narration by Ibn Abī Malīkah:

“You are narrating ḥadīths from the Messenger of Allah in which you differ. Those after you will differ even more. So do not narrate anything. Say: ‘Between us and you is the Book of Allah. Deem its lawful as ḥalāl and its unlawful as ḥarām.’”

This almost mirrors the phrase condemned in the earlier Hadith: “Between us and you is the Book of Allah.” If the Prophet allegedly warned against those who say such things, then how can the same words be attributed approvingly to Abu Bakr, his closest companion and first caliph?

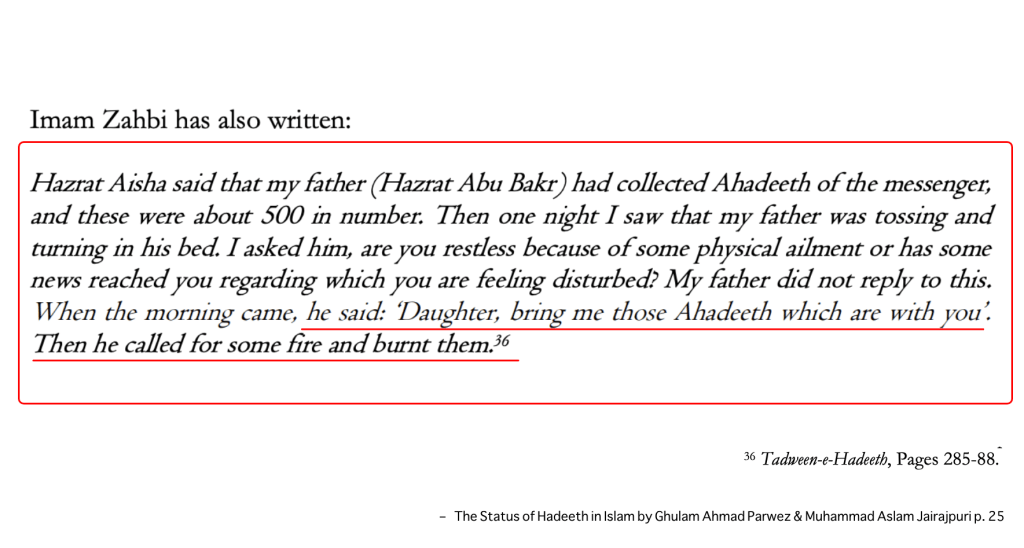

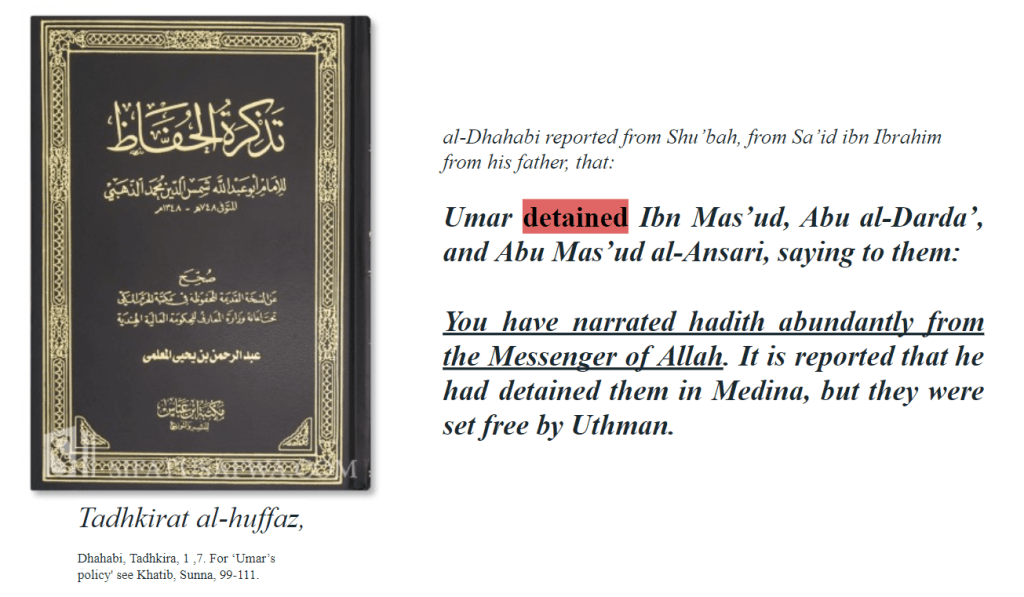

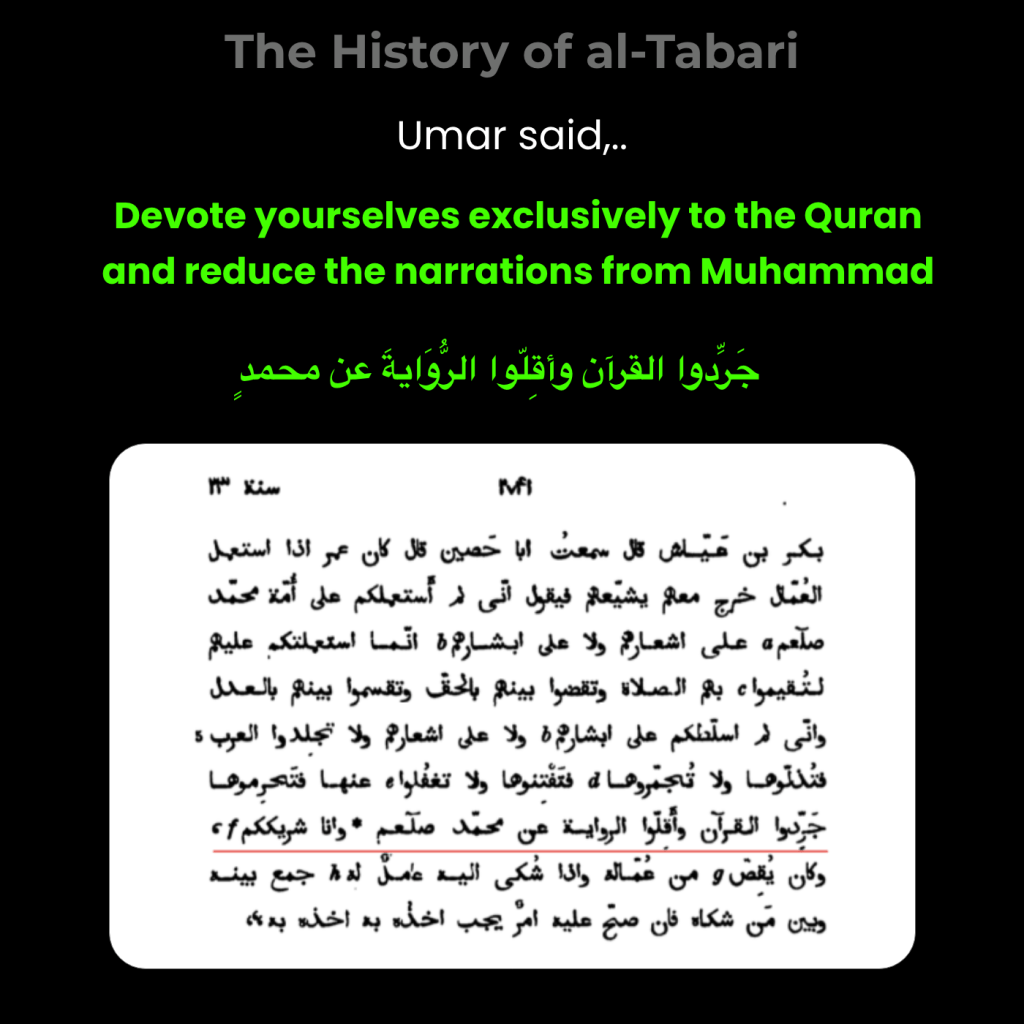

This is not an isolated incident. Numerous historical sources indicate that both Abū Bakr and ʿUmar discouraged the narration and transmission of Hadith. In some reports, they are even said to have burned early Hadith compilations and prohibited companions from spreading them.

The implication is clear: Hadith like those in Ibn Majah and Abu Dawud appear to have been crafted specifically to counter the early policy of restricting Hadith narrations—policies held by those who would have known the Prophet best. In doing so, later transmitters ironically placed the Prophet in conflict with his own companions, deploying his voice to undermine the very ethos of Quranic sufficiency that they upheld.

In short, the Hadith corpus not only contradicts itself—it also contradicts the legacy of the Prophet’s closest companions, who actively discouraged the spread of Hadith. Unlike the Quran, which was meticulously compiled and preserved under their leadership, no similar effort was made by the four rightly guided caliphs to record or catalog Hadith. On the contrary, the surviving reports portray them as cautious—if not outright hostile—toward the widespread narration of Hadith, fearing it would lead to confusion and division.

Here is an extended version of the narration.

Majallat al-Jāmiʿa al-Islāmiyya bi-l-Madīna al-Munawwara

The Era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs:

Things continued as before, and during the era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs, the situation did not change. The views of these caliphs regarding strictness in narration and caution in writing were an extension of the opinions of their fellow Companions during the time of the Prophet ﷺ. For example, Abu Bakr collected some hadiths and then burned them. Al-Dhahabi, with his chain of narration, said: Al-Qasim ibn Muhammad told me that Aisha said: My father collected the hadiths of the Messenger of Allah ﷺ, and they were five hundred hadiths. He spent the night turning restlessly. She said: I was distressed and asked, ‘Are you restless because of an illness or something that worries you?’ In the morning, he said, ‘O my daughter! Bring me the hadiths you have.’ So I brought them to him, and he called for fire and burned them. I asked, ‘Why did you burn them?’ He said, ‘I feared that I might die while they were with me, and there might be hadiths from a man whom I trusted and considered reliable, but he was not as he told me; thus, I would have transmitted something that is not correct.'” [33]

عصر الخلفاء الراشدين:

سار الأمر على ما تقدم، حتى إذا كان عهد الخلفاء الراشدين لم يتغير الحال، فقد كانت آراء هؤلاء الخلفاء في التشدد في الرواية والتورع عن الكتابة امتدادا لآراء إخوانهم الصحابة في عصر الرسول ﷺ!فهذا أبو بكر يجمع بعض الأحاديث ثم يحرقها، يقول الذهبي بسنده: حدثني القاسم بن محمد قالت عائشة: جمع أبي الحديث عن رسول الله ﷺ، وكانت خمسمائة حديث فبات ليلته يتقلب كثيرا، قالت فغمني فقلت: أتتقلب بشكوى أو لشيء يقلقك؟ فلما أصبح قال: أي بنية!هلمي الأحاديث التي عندك، فجئته بها فدعا بنار فحرقها، فقلت: لم أحرقتها؟ قال: خشيت أن أموت وهي عندي فيكون فيها أحاديث عن رجل قد ائتمنته ووثقت، ولم يكن كما حدثني؛ فأكون قد نقلت ذاك فهذا لا يصح“.اهـ[٣٣].اهـ[٣٣].

Additional References:

Original material for this article can be found here: