Every messenger is sent speaking the clear language of his people:

[14:4] We did not send any messenger except (to preach) in the tongue of his people, in order to clarify things for them. GOD then sends astray whomever He wills, and guides whomever He wills. He is the Almighty, the Most Wise.

وَمَآ أَرْسَلْنَا مِن رَّسُولٍ إِلَّا بِلِسَانِ قَوْمِهِۦ لِيُبَيِّنَ لَهُمْ فَيُضِلُّ ٱللَّهُ مَن يَشَآءُ وَيَهْدِى مَن يَشَآءُ وَهُوَ ٱلْعَزِيزُ ٱلْحَكِيمُ

In the case of the Quran, this divine speech was revealed in the precise idiom of 7th-century Hijazi Arabic—a dialect acutely familiar to its first recipients. Verses like 12:2, 26:195, and 39:28 confirm the Quran’s linguistic purity and clarity. (See also 41:3, 41:44, 42:7, 43:4, 46:12).

[12:2] We have revealed it an Arabic Quran, that you may understand.

إِنَّآ أَنزَلْنَـٰهُ قُرْءَٰنًا عَرَبِيًّا لَّعَلَّكُمْ تَعْقِلُونَ

[26:193] The Honest Spirit (Gabriel) came down with it.

[26:194] To reveal it into your heart, that you may be one of the warners.

[26:195] In a perfect Arabic tongue.(١٩٣) نَزَلَ بِهِ ٱلرُّوحُ ٱلْأَمِينُ

(١٩٤) عَلَىٰ قَلْبِكَ لِتَكُونَ مِنَ ٱلْمُنذِرِينَ

(١٩٥) بِلِسَانٍ عَرَبِىٍّ مُّبِينٍ[39:28] An Arabic Quran, without any ambiguity, that they may be righteous.

قُرْءَانًا عَرَبِيًّا غَيْرَ ذِى عِوَجٍ لَّعَلَّهُمْ يَتَّقُونَ

The Quran’s eloquence—its rhythm, word choice, and syntactic intricacy—was itself a miracle, stunning even its fiercest critics. The Arabs accused the Prophet of sorcery, poetry, and hallucination because they were bewildered by the literary force of the verses:

[16:103] We are fully aware that they say, “A human being is teaching him!” The tongue of the source they hint at is non-Arabic, and this is a perfect Arabic tongue.

وَلَقَدْ نَعْلَمُ أَنَّهُمْ يَقُولُونَ إِنَّمَا يُعَلِّمُهُۥ بَشَرٌ لِّسَانُ ٱلَّذِى يُلْحِدُونَ إِلَيْهِ أَعْجَمِىٌّ وَهَـٰذَا لِسَانٌ عَرَبِىٌّ مُّبِينٌ

[21:5] They even said, “Hallucinations,” “He made it up,” and, “He is a poet. Let him show us a miracle like those of the previous messengers.”

بَلْ قَالُوٓا۟ أَضْغَـٰثُ أَحْلَـٰمٍۭ بَلِ ٱفْتَرَىٰهُ بَلْ هُوَ شَاعِرٌ فَلْيَأْتِنَا بِـَٔايَةٍ كَمَآ أُرْسِلَ ٱلْأَوَّلُونَ

[52:30] They may say, “He is a poet; let us just wait until he is dead.”

أَمْ يَقُولُونَ شَاعِرٌ نَّتَرَبَّصُ بِهِۦ رَيْبَ ٱلْمَنُونِ

However, today no one speaks the exact Arabic of the 7th century when the Quran was first revealed. The further we are from the Prophet’s time, the more difficult it becomes to discern the linguistic fingerprints of divine speech. The original criteria—namely the unparalleled purity of its Arabic—can no longer be independently verified by the average reader or scholar.

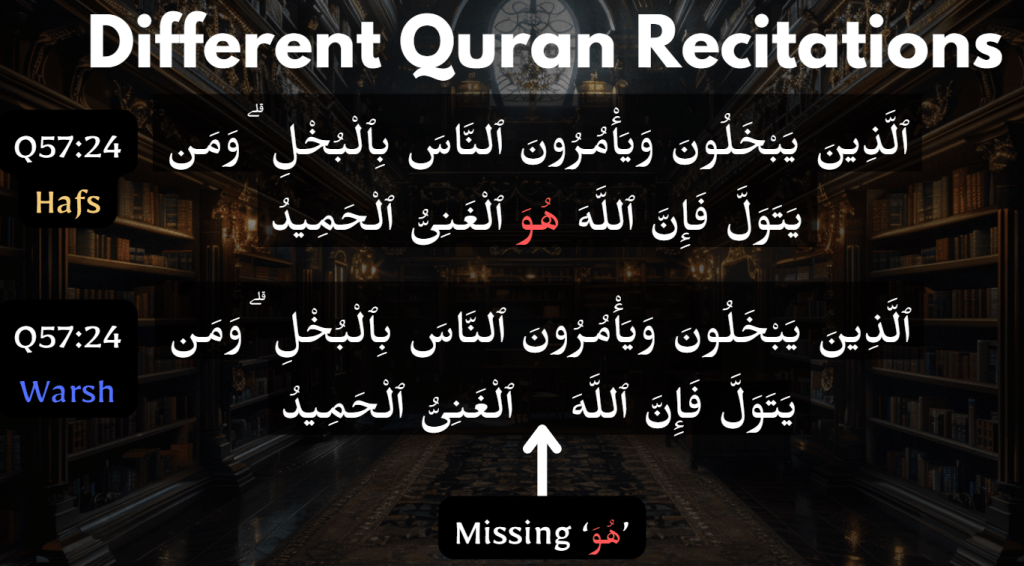

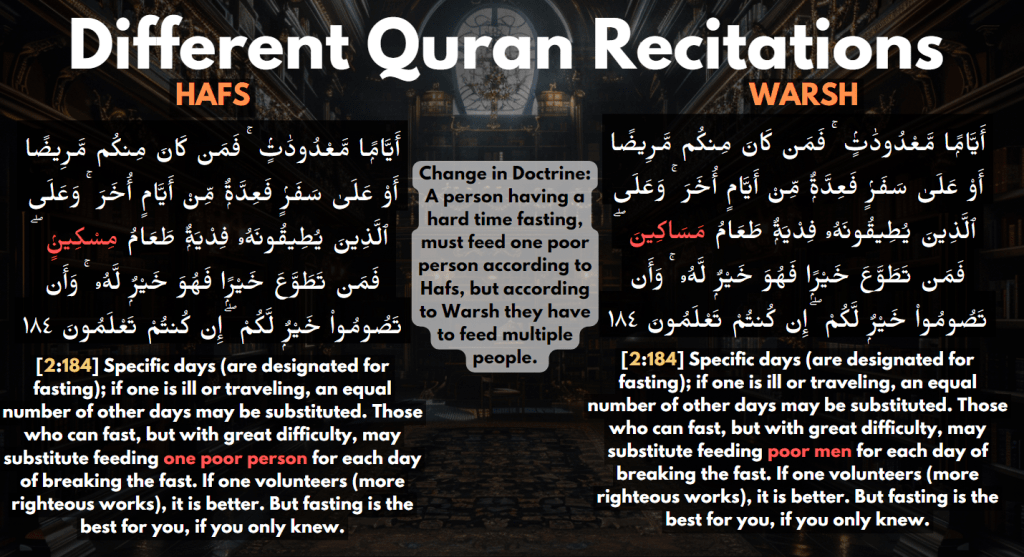

This difficulty is compounded by the existence of multiple canonical recitations (qirāʾāt), which differ in grammar, vocabulary, and syntax. Though they are all said to descend from the same divine source, the linguistic differences between them are significant enough that no one can identify which represents the precise original revelation purely from the Arabic alone. As a result, Muslims are told to accept all variants as equally Qur’anic, even if their forms diverge.

Worse still, centuries of habituation to the Quran’s style have dulled the edge of its distinctiveness. Fabricated verses and poetic imitations are now more easily passed off as genuine Quranic text. The average Muslim—lacking exposure to the original 7th-century linguistic context—can no longer reliably distinguish between the inspired and the imitative.

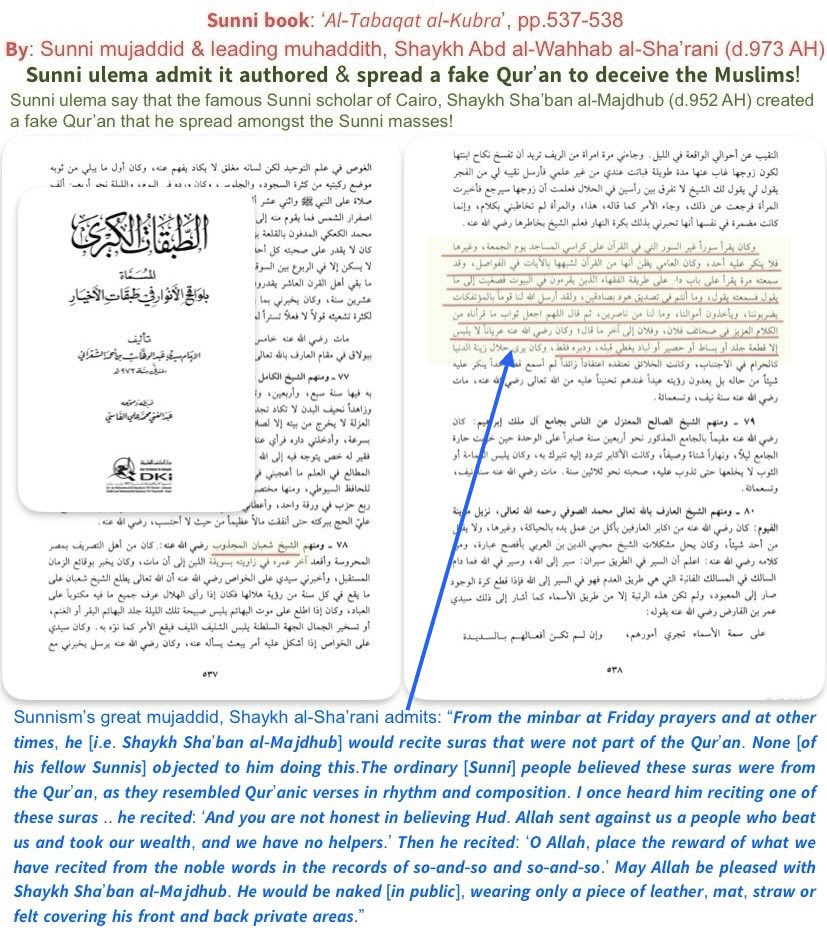

An example of this can be seen in a striking account recorded in al-Ṭabaqāt al-Kubrā (pp. 537–538) by the revered Sunni scholar and mujaddid, Shaykh ʿAbd al-Wahhāb al-Shaʿrānī (d. 973 AH). He documents the case of a renowned mystic, Shaykh Shaʿbān al-Majdhūb, whose recitations—though not from the Quran—were delivered in such a Quran-like style that the public believed them to be scripture. No one objected. The masses, unable to tell the difference, treated his words with reverence. His fabricated surahs, complete with rhyme and cadence, passed as revelation.

Excerpt: 𝘈𝘭-𝘛𝘢𝘣𝘢𝘲𝘢𝘵 𝘢𝘭-𝘒𝘶𝘣𝘳𝘢’ by Shaykh Abd al-Wahhab al-Sha’rani

The following link provides an online version of this book, with the passage on pages 546-547. Here is the original Arabic text along with the translation:

ومنهم الشيخ شعبان المجذوب رضي االله عنه

كان من أهل التصريف بمصر المحروسة وأقعد آخر عمره في زاويته بسويقة اللبن إلى أن مات، وكان يخبر بوقائع الزمان المستقبل، وأخبرني سيدي على الخواص رضي االله عنه أن االله تعالى يطلع الشيخ شعبان على ما يقع في كل سنة من رؤية هلالها فكان إذا رأى الهلال عرف جميع ما فيه مكتوبا ً على العباد، وكان إذا اطلع على موت البهائم يلبس صبيحة تلك الليلة جلد البهائم البقر أو الغنم أو تسخير الجمال الجهة السلطنة يلبس الشليف الليف فيقع الأمر كما نوه به. وكان سيدي على الخواص إذا أشكل عليه أمر يبعث يسأله عنه، وكان رضي االله عنه يرسل يخبرني مع النقيب عن أحوالي الواقعة في الليل. وجاءني مرة امرأة من الريف تريد أن تفسخ نكاح ابنتها لكون زوجها غاب عنها مدة طويلة فباتت عندي من غير علمي فأرسل نقيبه لي من الفجر يقول لي يقول لك الشيخ لا تفرق بين رأسين في الحلال فعلمت أن زوجها سيرجع فأخبرت المرأة فرجعت عن ذلك، وجاء الأمر كما قاله، هذا، والمرأة لم تخاطبني بكلام، وإنما كانت مضمرة في نفسها أا تحبرني بذلك بكرة النهار فعلم الشيخ بخاطرها رضي االله عنه.

وكان يقرأ سور ًا غير السور التي في القرآن على كراسي المساجد يوم الجمعة، وغيرها فلا ينكر عليه أحد، وكان العامي يظن أا من القرآن لشبهها بالآيات في الفواصل، وقد سمعته مرة يقرأ على باب دار على طريقة الفقهاء الذين يقرءون في البيوت فصغيت إلى ما يقول فسمعته يقول، وما أنتم في تصديق هود بصادقين، ولقد أرسل االله لنا قوما ً بالمؤتفكات يضربوننا، ويأخذون أموالنا، وما لنا من ناصرين، ثم قال اللهم اجعل ثواب ما قرأناه من الكلام العزيز في صحائف فلان، وفلان إلى آخر ما قال؛ وكان رضي االله عنه عريانا ً لا يلبس إلا قطعة جلد أو بساط أو حصير أو لباد يغطي قبله، ودبره فقط، وكان يرى حلال زينة الدنيا كالحرام في الاجتناب، وكانت الخلائق تعتقله اعتقاد ًا زائد ًا لم أسمع قط أحد ًا ينكر عليه شيئا ً من حاله بل يعدون رؤيته عيد ًا عندهم تحنينا ً عليه من االله تعالى رضي االله عنه، مات رضي االله عنه سنة نيف، وتسعمائة.

Among them was Shaykh Shaʿbān al-Majdhūb, may God be pleased with him.

He was among the people of taṣrīf (spiritual control and influence) in Cairo. In the final part of his life, he remained seated in his spiritual retreat in Sūwayqat al-Laban until he died. He used to speak of future events. My master, Sīdī ʿAlī al-Khawwāṣ (may God be pleased with him), told me that God would unveil to Shaykh Shaʿbān everything that would happen in a given year from the moment he sighted the new moon (hilāl). When he saw the crescent, he would know all that was written for the servants in that year. When he became aware of the death of livestock, he would wear the hide of cattle or sheep on the morning after that night; and if it was related to the conscription or deployment of camels for the service of the sultanate, he would wear palm fiber ropes, and events would unfold exactly as he had indicated. And when Sīdī ʿAlī al-Khawwāṣ was confused about something, he would send someone to ask Shaykh Shaʿbān about it. The Shaykh (may God be pleased with him) would often send word through his assistant informing me of what had transpired with me during the night. One time, a woman from the countryside came to me wanting to annul her daughter’s marriage because her husband had been absent for a long time. She stayed the night in my home without my knowledge. At dawn, the Shaykh’s assistant came to me and said: “The Shaykh says to you: Do not separate two who are lawfully joined.” So I knew that her husband would return. I informed the woman, and she abandoned her plan. Events unfolded just as he had said — and the woman had not spoken a word to me. She had only intended to tell me about it the following morning, yet the Shaykh was aware of her unspoken thoughts (may God be pleased with him).

He used to recite surahs that were not from the Qur’an while seated on mosque platforms on Fridays and other days, and no one objected to him. The common people assumed these were from the Qur’an due to their similarity in phrasing and rhythm. I once heard him reciting at the door of a house in the style of jurists who recite in private homes. I listened closely and heard him say: “And you are not among those who believed Hūd to be truthful. Verily, God sent against us a people from the overthrown cities (al-muʾtafikāt); they struck us and seized our wealth, and we had no helper.” Then he said: “O Allah, make the reward of what we recited from the noble words [i.e., the honored speech] to be written in the records of so-and-so and so-and-so…” and continued until he finished. And (may God be pleased with him), he would be naked—wearing nothing but a piece of hide, or mat, or coarse cloth, or felt, simply to cover his front and back. And he saw all of this as lawful. He avoided the adornments of the world as one would avoid the forbidden. The people held an extraordinary reverence for him, and I never heard anyone criticize any aspect of his conduct. On the contrary, they considered merely seeing him a festive occasion, a sign of God’s mercy upon him. May God be pleased with him. He passed away in the early 900s AH.

This passage offers a powerful, real-world demonstration that the linguistic miracle of the Qur’an was time-bound, meant to astonish and persuade its immediate audience—the native Arab speakers of 7th-century Hijaz—whose literary culture was uniquely primed to recognize its inimitability.

As shown in the passage, Shaykh Shaʿbān al-Majdhūb, a revered mystic in 16th-century Cairo, is reported to have recited verses not found in the Qur’an while sitting publicly in mosques on Fridays and other occasions—and yet, not a single person objected. Why? Because the general public mistook his invented verses for actual Qur’anic revelation, so closely did they resemble the form, rhythm, and rhetorical structure of the Qur’an.

This was not an isolated case in some remote village—it occurred in Cairo, centuries after Islam had become the dominant force across Egypt. The city was not just a cultural center, but a hub of Islamic scholarship, filled with mosques, students of knowledge, and the religious elite. Yet, despite this environment steeped in Qur’anic recitation, the linguistic illusion crafted by one mystic went unchallenged.

The implication is striking: even among devout Muslims, centuries removed from the Quran’s original context, the ability to distinguish between divine revelation and human imitation had been lost. The “miracle” of the Quran’s Arabic—so clear and decisive to its original audience—had become indistinct to later generations, no longer accessible by intuition or language alone.

This historical anecdote underscores that the Qur’an’s linguistic challenge was tailored to the unique conditions of its time and place. The force of its language was immediately felt by its first hearers—but that clarity diminishes over time, especially when Arabic itself evolves, and fewer people possess the linguistic sensitivity to appreciate or judge its distinction.

The case of Shaykh Shaʿbān al-Majdhūb is not just a curiosity; it is a caution. It shows that language alone cannot serve as a universal or timeless proof unless its audience shares the same linguistic and cultural frame of reference. And today, no one—Arab or non-Arab—speaks the precise tongue of the Qur’an’s original hearers. The miracle, then, was for them.

The Quranic Challenge

This raises a profound question regarding the Quran’s oft-cited challenge:

[2:23] If you have any doubt regarding what we revealed to our servant, then produce one sura like these, and call upon your own witnesses against GOD, if you are truthful.

وَإِن كُنتُمْ فِى رَيْبٍ مِّمَّا نَزَّلْنَا عَلَىٰ عَبْدِنَا فَأْتُوا۟ بِسُورَةٍ مِّن مِّثْلِهِۦ وَٱدْعُوا۟ شُهَدَآءَكُم مِّن دُونِ ٱللَّهِ إِن كُنتُمْ صَـٰدِقِينَ

[10:38] If they say, “He fabricated it,” say, “Then produce one sura like these, and invite whomever you wish, other than GOD, if you are truthful.”

أَمْ يَقُولُونَ ٱفْتَرَىٰهُ قُلْ فَأْتُوا۟ بِسُورَةٍ مِّثْلِهِۦ وَٱدْعُوا۟ مَنِ ٱسْتَطَعْتُم مِّن دُونِ ٱللَّهِ إِن كُنتُمْ صَـٰدِقِينَ

[11:13] If they say, “He fabricated (the Quran),” tell them, “Then produce ten suras like these, fabricated, and invite whomever you can, other than GOD, if you are truthful.”

أَمْ يَقُولُونَ ٱفْتَرَىٰهُ قُلْ فَأْتُوا۟ بِعَشْرِ سُوَرٍ مِّثْلِهِۦ مُفْتَرَيَـٰتٍ وَٱدْعُوا۟ مَنِ ٱسْتَطَعْتُم مِّن دُونِ ٱللَّهِ إِن كُنتُمْ صَـٰدِقِينَ

[17:88] Say, “If all the humans and all the jinns banded together in order to produce a Quran like this, they can never produce anything like it, no matter how much assistance they lent one another.”

قُل لَّئِنِ ٱجْتَمَعَتِ ٱلْإِنسُ وَٱلْجِنُّ عَلَىٰٓ أَن يَأْتُوا۟ بِمِثْلِ هَـٰذَا ٱلْقُرْءَانِ لَا يَأْتُونَ بِمِثْلِهِۦ وَلَوْ كَانَ بَعْضُهُمْ لِبَعْضٍ ظَهِيرًا

At first glance, these verses seem to present an open linguistic challenge—an invitation to replicate the Quran’s literary force. And in the 7th century, the challenge was indeed meaningful. It was delivered to a people whose oral mastery of the Arabic language made them uniquely equipped to recognize its inimitability. The Prophet’s adversaries did not meet the challenge because they could not. The Qur’an’s language struck them as beyond human capacity.

But fast forward to the present: How can this challenge be meaningfully assessed today?

The linguistic context has changed. There is no objective standard left to judge whether a sura “matches” the Qur’an in style, rhetoric, or impact. The original Arabic has evolved. The oral culture that once made such a comparison intuitive is gone. And as the example of Shaykh Shaʿbān al-Majdhūb illustrates, even entire Muslim communities—including scholars—have mistaken fabricated texts for divine revelation.

This highlights a deeper truth: the Quran’s linguistic miracle, like the miracles of earlier prophets, was never meant to be timeless in form—it was timely in function.

When Moses cast down his staff and it became a serpent, or parted the sea by God’s command, these signs were undeniable—but only to those who saw them with their own eyes. No one today can observe those miracles directly. Outside of divine revelation, their reality must be accepted on faith, not by replication.

In the same way, when Jesus healed the blind and the leper or raised the dead by God’s leave, the impact of those miracles was confined to their moment in time. They were persuasive to those who witnessed them—but for every generation after, belief in those signs depends not on firsthand evidence, but in trust of God’s scripture.

So too with the Qur’an’s linguistic inimitability. It was a miracle perfectly tailored to its first hearers—a people of poetry, rhetoric, and oral mastery. They understood instantly that what they were hearing was not from any human source. But centuries later, the conditions that made that recognition possible are gone.

What was once unchallengeable has now become unverifiable. Therefore, the Quran’s challenge cannot rest on linguistic excellence alone—not in a way that remains objectively testable today. To truly grasp the nature of this challenge, we must look beyond linguistics. Beyond imitation. Beyond the surface of style and sound. We must ask what makes the Qur’an inimitable in essence, not merely in form.

Check out the following article to better understand the actual challenge of the Quran: