Many people, both Muslims and non-Muslims, often assume that the meanings of the words in the Quran are clear-cut, universally agreed upon, and linguistically obvious. This assumption can lead to the mistaken belief that interpreting the Quran is a straightforward task requiring little more than a dictionary and a literal reading. However, even a brief exploration into the linguistic background of the Quran reveals a much more nuanced reality. In fact, disagreement begins with the very title of the book itself. The term Qur’an—so central and seemingly familiar—is the subject of scholarly debate concerning its exact linguistic root, derivation, and even its correct pronunciation.

On pages 24–25 of An Introduction to the Sciences of the Qur’aan by Yasir Qadhi, the author highlights how classical scholars have presented multiple—and at times conflicting—opinions regarding the origin and meaning of the word Qur’an. This demonstrates that even foundational terms within the revelation are subject to layered interpretation and scholarly debate. The text states:

There are a number of different opinions concerning the linguistic meaning of the word ‘qur’aan’.

The most popular opinion, and the opinion held by at-Tabaree (d. 310 A.H.), is that the word ‘qur’aan’ is derived from qara’a, which means, ‘to read, to recite’. ‘Qur’aan’ would then be the verbal noun (masdar) of qara’a, and thus translates as ‘The Recitation’ or ‘The Reading’. Allaah says in reference to the Qur’aan,

وَقُرْآنًا فَرَقْنَاهُ

“And (it is) a Qur’aan which We have divided into parts…” [17:106]

and He says,

إِنَّ عَلَيْنَا جَمْعَهُ وَقُرْآنَهُ فَإِذَا قَرَأْنَاهُ فَاتَّبِعْ قُرْآنَهُ

“It is for Us to collect it and to Recite it (Ar. qur’aanahu). When We have recited it, then follow its Recitation (Ar. qur’aanahu).”

On the other hand, Imaam ash-Shaafi’ee (d. 204 A.H.) held the view that the word ‘qur’aan’ was a proper noun that was not derived from any other word, just like ‘Tawrah’ or ‘Injeel’. He recited the word without a hamza, such that ‘Qur’aan’ would rhyme with the English word ‘lawn’. One of the qira’aat pronounced it this way.

Another opinion states that the word ‘qur’aan’ is from the root qarana, which means, ‘to join, to associate’. For example, the pilgrimage in which ‘Umrah and Hajj are combined is called Hajj Qiraan, from the same root word. Therefore the meaning of the word ‘qur’aan’ would be, ‘That which is joined together,’ because its verses and soorahs are combined to form this book. In this case, the word would be pronounced the same way as Imaam ash-Shaafi’ee pronounced it, without the hamza.

A fourth opinion is that ‘qur’aan’ comes from the word qaraa’in, which means ‘to resemble, to be similar to’. Hence, the Qur’aan is composed of verses that aid one another in comprehension, and soorahs that resemble each other in beauty and prose.

Yet another opinion is that ‘Qur’aan’ is from qar’, which means ‘to combine’. It is called such since it combines stories, commands, promises and punishments.

However, the opinion that is the strongest, and the one that the majority of scholars hold, is the first one, namely that the word ‘qur’aan’ is the verbal noun of qara’a and therefore means, ‘The Recitation’. The proof for this is that it is named such in the Qur’aan (and most of the qira’aat pronounce the word with a hamza), and the word conforms with Arabic grammar as the verbal noun of qara’a.

It may be asked: how does one explain the fact that some qira’aat pronounce the word ‘Qur’aan’ without a hamza, as it is well known that all the qira’aat are equally authentic (as shall be discussed in greater detail)? The response to this question is that this particular pronunciation is due to the peculiar rules of recitation (tajweed) of those qira’aat, and affects many words. In other words, the qira’aat that pronounce the word ‘Qur’aan’ without a hamza do not intend to change the pronunciation of the word ‘Qur’aan’ itself, but rather this occurs due to a particular rule of recitation (tajweed) that affects many words in the Qur’aan, including the pronunciation of the word ‘Qur’aan.’ Therefore, even though the pronunciation of the word ‘Qur’aan’ is different in these qira’aat, the actual word is still the same.

Additionally, according to Al-Shāfiʿī (d. 204), every time he used the word قُرَان in his books, it was without a sukūn on the ر and without أ. So, it’s read as “Qurān,” not “Qur’ān,” as is usually stated today. This is because of his preference and the specific recitation of the Qur’ān he preferred, which was the Qirā’ah of Ibn Kat͟hīr Al-Makkī.

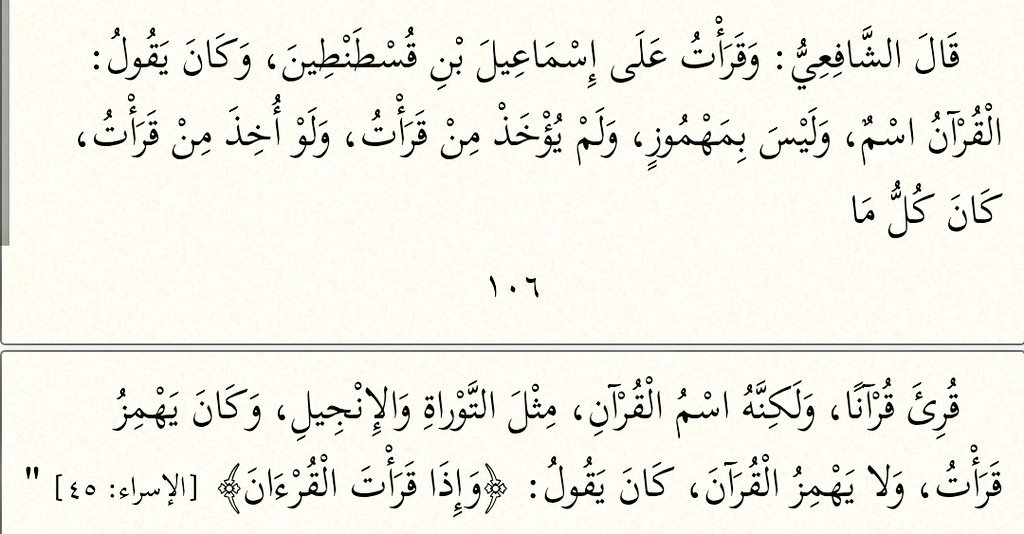

He said, “I recited to Ismā’īl b. Qusṭanṭīn. He used to say, ‘The word قُرَان is an Ism*. It does not have a Hamzah, and it is not taken from the root of قرأتُ. If that was the case, everything that is read would’ve been Qur’ān. Rather, it’s an Ism: القُرَان.’ He used to read قَرَأت with a Hamzah but قران without it. So, he would recite the verse as: ”وَإذَا قَرَأْتَ القُرَان“ [Ādāb Al-Shāfiʿī Wa Manāqibuh, p. 106-107].

In conclusion, while many assume that the term Qur’an has a singular, universally agreed-upon meaning, classical scholarship paints a far more complex picture. As shown in the views of early scholars such as at-Ṭabarī and ash-Shāfiʿī, there is not only disagreement over the root of the word—whether it comes from qara’a (to recite), qarana (to join), qarā’in (resemblances), or qar’ (to combine)—but even over its very pronunciation.

Some, like at-Ṭabarī, maintain that Qur’an is a verbal noun meaning “The Recitation,” a view supported by its grammatical form and Qur’anic usage. Others, such as ash-Shāfiʿī, argued that Qur’an is a proper noun not derived from any root, reciting it without the hamzah in line with the Qirāʾah of Ibn Kathīr al-Makkī.

This range of interpretations highlights not only the linguistic complexity of the Qur’anic text but also the inherent limitations and subjectivity of those interpreting it. Each of the scholars cited approached the text through their own assumptions, methodologies, and biases, often arriving at differing conclusions. Yet, ironically, their followers frequently treat their preferred scholar’s views as definitive and unquestionable. In reality, no scholar possesses a monopoly on truth. The very fact that there is disagreement—even over the name Qur’an itself—reveals that what is often presented as absolute is, in fact, interpretive. Acknowledging this challenges the assumption that scholarly consensus reflects divine certainty, rather than human reasoning shaped by context and perspective.