In daily life, people navigate decisions using different approaches, often without realizing it. Sometimes, we rely on imitation (mimetics)—following established norms, routines, or the behaviors of those before us. Other times, we use reasoning.

Consider a doctor treating a patient. If the doctor follows a mimetic approach, they might apply textbook treatments precisely as written, assuming that what worked in clinical trials will work in all cases. However, if they use reasoning, they consider the patient’s specific condition, medical history, and unique circumstances, adapting their treatment accordingly. While medical guidelines provide a structured framework, a real-world application often requires flexibility based on specific circumstances.

Similarly, in learning a language, some students adopt mimetic learning, memorizing phrases without truly understanding the rules behind them. Others apply reasoning, analyzing grammar, sentence structure, and context to adapt their communication. While mimetic learning helps with basic recall, true fluency requires reasoning and adaptability—adjusting to context rather than rigidly following set phrases.

Religious practice operates the same way. Some aspects of faith require strict imitation (mimetic approach), while others require reasoning. The challenge is determining which method applies in different areas of religious life.

Sunnis: Religion is Mostly Mimetic

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam, comprising roughly 85-90% of Muslims worldwide. They have a famous maxim that they abide by: “Whoever imitates the people becomes one of them.” So, for them, the foundation of being Mulsim is based on imitation (tradition) more than anything else. They claim this was how the prophet exemplified righteousness, which is also how all believers should imitate. In the following Hadith found both in Bukhari and Muslim, it demonstrates they ascribe this way of thinking to the prophet.

Narrated Ibn `Abbas: Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) used to let his hair hang down while the infidels used to part their hair. The people of the Scriptures were used to letting their hair hang down and Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) liked to follow the people of the Scriptures in the matters about which he was not instructed otherwise. Then Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) parted his hair.

حَدَّثَنَا يَحْيَى بْنُ بُكَيْرٍ، حَدَّثَنَا اللَّيْثُ، عَنْ يُونُسَ، عَنِ ابْنِ شِهَابٍ، قَالَ أَخْبَرَنِي عُبَيْدُ اللَّهِ بْنُ عَبْدِ اللَّهِ، عَنِ ابْنِ عَبَّاسٍ ـ رضى الله عنهما أَنَّ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم كَانَ يَسْدِلُ شَعَرَهُ، وَكَانَ الْمُشْرِكُونَ يَفْرُقُونَ رُءُوسَهُمْ فَكَانَ أَهْلُ الْكِتَابِ يَسْدِلُونَ رُءُوسَهُمْ، وَكَانَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم يُحِبُّ مُوَافَقَةَ أَهْلِ الْكِتَابِ فِيمَا لَمْ يُؤْمَرْ فِيهِ بِشَىْءٍ، ثُمَّ فَرَقَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم رَأْسَهُ.

Sahih al-Bukhari 3558

https://sunnah.com/bukhari:3558

The Sunni’s theological basis is the belief that the Prophet Muhammad left the best and most complete example of how to live and that imitating his life as closely as possible is the key to righteousness and salvation. For Sunnis, the Prophet’s actions, words, and even personal habits are considered a direct guide for all aspects of life—from religious obligations to daily routines. This belief stems from the idea that God not only sent down the Quran as divine guidance but also provided Muhammad’s life as a perfect demonstration of how to implement it. As a result, Sunnis rely heavily on the Hadith and the Sunnah, believing that every situation they face has an answer that can be found in his example.

The core Sunni belief is that the Prophet’s life, his “sunnah,” was the most perfect embodiment of Islam, and therefore, the best way to please God is to mirror his actions as precisely as possible. This extends beyond just religious rituals like prayer and fasting; it includes how he dressed, how he ate, how he slept, how he brushed his teeth, what he smelled like, or how he trimmed his beard and mustache. Many Sunnis hold the conviction that the more one resembles the Prophet in both major and minor details, the closer they are to achieving true piety and ultimately securing paradise.

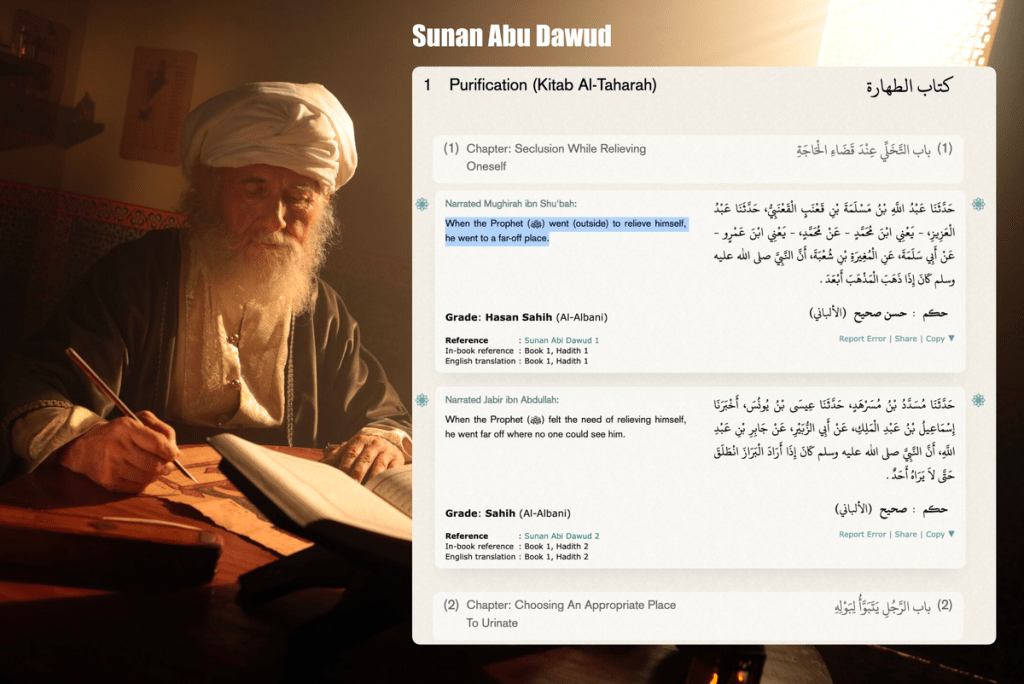

Consider that Abu Dawud, one of the most revered compilers of Hadith, engaged in extensive contemplation to determine the Hadith that would best honor the Prophet for the inaugural chapter of his compilation. After what must have been much introspection and reflection, he ultimately decided to spend the first couple hundred of Hadith discussing how the prophet urinated or defecated.

The Sunni predominantly mimetic approach to religion means that their scholars and jurists often seek answers to contemporary issues not by interpreting broad Quranic principles but by looking for precedents in the Prophet’s actions. Whether it’s a question about governance, finance, diet, or personal conduct, the answer is often sought in how they believe Muhammad himself supposedly behaved. This belief system creates a highly traditionalist outlook, where religious rulings and social norms are based on false historical precedents rather than the use of logic and reason. Believing that if they can just find the right case study regarding the prophet and act that out exactly, it will give them a successful outcome.

As Ibn Hanbal famously taught:

“A flawed Hadith is preferable to me than a scholar’s opinion or Qiyas [analogical reasoning],” …Ibn Hanbal reminded his students, commanded to take their religion from on high and not rely on the flawed faculty of reason.1

For Hanbal, the purity of faith rested on unwavering adherence to the Hadith and Sunnah, which he considered the ultimate authority in understanding matters of religion. From this sort of understanding, other notable figures like “Sa’id ibn Mansur narrated on the authority of ‘Isa ibn Yunus on the authority of al-Awza’i on the authority of Makhul, who said: “The Quran needs the Saunnah more than the Sunnah needs the Quran.” The same statement was related by al-Awza’i on the authority of Yahya ibn Abi Kathir, who was also reported to have said, “The Sunnah came to rule over the Qur’ān, it is not the Qur’ān that rules over the Sunnah.“

This Sunni framework stands in contrast to much of logic and reasoning, which focuses on interpreting Quranic laws based on principles and adaptability. Instead of asking, “What did the Prophet do?” a rational approach asks, “What does the Quranic principle teach, and how do we apply it in whatever context we are facing?”. The Sunni reliance on mimetics results in rigid legalism, where deviation from established traditions is often viewed as a threat to religious authenticity. An example that is often cited as a refutation against the use of logic and reason for religious judgments is in the following Hadith from the Muwatta of Malik, where the punishment for cutting off the finger of a woman is 30 camels for three fingers and twenty camels for four. This is to emphasize that one should not try to use logic and reasoning in their religious decisions but only to follow the Sunnah as it is.

ibn Abi Abd ar-Rahman said, “I asked Said ibn al Musayyab, ‘How much for the finger of a woman?’ He said, ‘Ten camels’ I said, ‘How much for two fingers?’ He said, ‘Twenty camels.’ I said, ‘How much for three?’ He said, ‘Thirty camels.’ I said, ‘How much for four?’ He said, ‘Twenty camels.’ I said, ‘When her wound is greater and her affliction stronger, is her blood-money then less?’ He said, ‘Are you an Iraqi?’ I said, ‘Rather, I am a scholar who seeks to verify things, or an ignorant man who seeks to learn.’ Said said, ‘It is the sunna, my nephew.’ “

Malik said, “What is done in our community about all the fingers of the hand being cut off is that its blood- money is complete. That is because when five fingers are cut, their blood-money is the blood-money of the hand: fifty camels. Each finger has ten camels.”

Malik said, “The reckoning of the fingers is thirty-three dinars for each fingertip, and that is three and a third shares of camels.”وَحَدَّثَنِي يَحْيَى، عَنْ مَالِكٍ، عَنْ رَبِيعَةَ بْنِ أَبِي عَبْدِ الرَّحْمَنِ، أَنَّهُ قَالَ سَأَلْتُ سَعِيدَ بْنَ الْمُسَيَّبِ كَمْ فِي إِصْبَعِ الْمَرْأَةِ فَقَالَ عَشْرٌ مِنَ الإِبِلِ . فَقُلْتُ كَمْ فِي إِصْبَعَيْنِ قَالَ عِشْرُونَ مِنَ الإِبِلِ . فَقُلْتُ كَمْ فِي ثَلاَثٍ فَقَالَ ثَلاَثُونَ مِنَ الإِبِلِ . فَقُلْتُ كَمْ فِي أَرْبَعٍ قَالَ عِشْرُونَ مِنَ الإِبِلِ . فَقُلْتُ حِينَ عَظُمَ جُرْحُهَا وَاشْتَدَّتْ مُصِيبَتُهَا نَقَصَ عَقْلُهَا فَقَالَ سَعِيدٌ أَعِرَاقِيٌّ أَنْتَ فَقُلْتُ بَلْ عَالِمٌ مُتَثَبِّتٌ أَوْ جَاهِلٌ مُتَعَلِّمٌ . فَقَالَ سَعِيدٌ هِيَ السُّنَّةُ يَا ابْنَ أَخِي . قَالَ مَالِكٌ الأَمْرُ عِنْدَنَا فِي أَصَابِعِ الْكَفِّ إِذَا قُطِعَتْ فَقَدْ تَمَّ عَقْلُهَا وَذَلِكَ أَنَّ خَمْسَ الأَصَابِعِ إِذَا قُطِعَتْ كَانَ عَقْلُهَا عَقْلَ الْكَفِّ خَمْسِينَ مِنَ الإِبِلِ فِي كُلِّ إِصْبَعٍ عَشَرَةٌ مِنَ الإِبِلِ . قَالَ مَالِكٌ وَحِسَابُ الأَصَابِعِ ثَلاَثَةٌ وَثَلاَثُونَ دِينَارٍ وَثُلُثُ دِينَارٍ فِي كُلِّ أَنْمُلَةٍ وَهِيَ مِنَ الإِبِلِ ثَلاَثُ فَرَائِضَ وَثُلُثُ فَرِيضَةٍ .

Muwatta Malik

https://sunnah.com/urn/515780

*For background, the reference to “being an Iraqi” is a jab against Abu Hanifa and his followers, who, prior to his rebranding by 11th-century scholars who made him out to be a staunch follower and advocate of Hadith, was originally viewed as a heretic amongst proto-sunnis (8th-10th-century) because of his emphasis on ra’y (reasoning) and qiyas (analogy) over Hadith.

Ultimately, the Sunni ideology views perfect imitation of the Prophet as the ultimate path to paradise, equating adherence to Hadith and Sunnah with obedience to God. However, this reliance on mimicry over reasoning raises important questions about whether faith should be rooted in imitation or in the deeper understanding of divine guidance.

Quran: Religion is Mostly Logic and Reason

The Sunni approach misunderstands the Quran’s guidance, which does not require blanket imitation of the prophet but instead encourages mimetic practice only in specific cases—primarily in rituals (manāsik), as will be discussed later, while adopting a logical approach to divine laws.

The Quran’s judicial foundation is designed for adaptability, emphasizing interpretation over rigid imitation. If God had willed, He could have revealed a book spanning endless volumes, prescribing solutions for every conceivable situation. Instead, He provides specific examples and overarching principles, guiding believers to use reason and discretion when navigating unique circumstances. This concept is reinforced in the following verse:

[31:27] If all the trees on earth were made into pens, and the ocean supplied the ink, augmented by seven more oceans, the words of GOD would not run out. GOD is Almighty, Most Wise.

This verse illustrates that divine wisdom is infinite, yet the Quran presents only what is essential for moral guidance. If it had attempted to detail every possible scenario, the sheer volume of knowledge required would surpass all the ink and paper on earth. Such a text would be impractical to transmit, overwhelming to comprehend, and impossible to fully implement. Instead, God provides the necessary examples and principles to address any ethical dilemma one may face in life. He also granted us the intellectual capacity to engage in reasoning, allowing for interpretation and adaptation as societies evolve. This ensures that divine guidance remains timeless, applicable, and relevant across all generations.

For example, the Quran provides simple principles rather than exact details regarding what to give to charity and how much. For instance, it commands us to give from what we love and to give the excess. This opens it up to the individual to utilize their discretion to how best to apply this concept in their own charitable giving. It personalizes the action because what is considered loved or excess may vary from person to person.

[3:92] You cannot attain righteousness until you give to charity from the possessions you love. Whatever you give to charity, GOD is fully aware thereof.

[2:219] They ask you about intoxicants and gambling: say, “In them there is a gross sin, and some benefits for the people. But their sinfulness far outweighs their benefit.” They also ask you what to give to charity: say, “The excess.” GOD thus clarifies the revelations for you, that you may reflect,

So when the Quran informs us that the messenger has set “a good example” for the believers, his example is not how he combed his hair, used the restroom, dressed, ate, or drank but the examples found in the Quran. If we explore the context of this statement, we see that when the hypocrites saw the parties ready to attack, the they were ready to flee; however, this only strengthened the faith of the prophet and the believers.

[33:12] The hypocrites and those with doubts in their hearts said, “What GOD and His messenger promised us was no more than an illusion!” [33:13] A group of them said, “O people of Yathrib, you cannot attain victory; go back.” Others made up excuses to the prophet: “Our homes are vulnerable,” when they were not vulnerable. They just wanted to flee. [33:14] Had the enemy invaded and asked them to join, they would have joined the enemy without hesitation.

[33:21] The messenger of GOD has set up a good example for those among you who seek GOD and the Last Day, and constantly think about GOD. [33:22] When the true believers saw the parties (ready to attack), they said, “This is what GOD and His messenger have promised us, and GOD and His messenger are truthful.” This (dangerous situation) only strengthened their faith and augmented their submission.

This shows that his example is the hermeneutic that we are to learn from and is not related to the mimetics of what he did. Further proof of this is that the term “a good example” is also used for Abraham, yet we know this refers to his overall devotion to God and not his personal habits, again, as found in the Quran.

[60:4] A good example has been set for you by Abraham and those with him. They said to their people, “We disown you and the idols that you worship besides GOD. We denounce you, and you will see nothing between us except animosity and hatred until you believe in GOD ALONE.” However, a mistake was committed by Abraham when he said to his father, “I will pray for your forgiveness, but I possess no power to protect you from GOD.” “Our Lord, we trust in You, and submit to You; to You is the final destiny. [60:5] “Our Lord, let us not be oppressed by those who disbelieved, and forgive us. You are the Almighty, Most Wise.” [60:6] A good example has been set by them for those who seek GOD and the Last Day. As for those who turn away, GOD is in no need (of them), Most Praiseworthy. [60:7] GOD may change the animosity between you and them into love. GOD is Omnipotent. GOD is Forgiver, Most Merciful.

This is because God’s book contains all the examples we need for our salvation. Therefore, any secondary source of law, such as the Hadith, has no religious authority in the religion.

[18:54] We have cited in this Quran every kind of example, but the human being is the most argumentative creature.

[17:89] We have cited for the people in this Quran all kinds of examples, but most people insist upon disbelieving.

Quran & Legal Reasoning

This concept of reasoning over mimetics can also be found in legal rulings. The legal rulings in the Quran are meant to be adaptable to time and place. The Quran sets the framework of what is permissible and puts forward the spirit of the law. The objective of the upholders of the Quran are to never exceed the limits that are set by the Quran, either the minimum or maximum, while still holding to the overall spirit of the law.

A good example of this is found in inheritance laws (4:7-8, 11-12, and 176). The Quran provides foundational guidelines for distribution, addressing specific cases such as when no will is left behind or when additional assets remain after a will has been executed, with a strong emphasis on ensuring women receive their rightful shares. However, it does not attempt to account for every possible familial arrangement. This is left to the individual to use their own discretion based on the principles of the Quran to figure out how to account for any other situation they face. Therefore, the Quran serves as a foundation upon which our legal system is built upon.

Additionally, another principle of the Quran is that we are to be equitable, just, and charitable. Today, through the technology and sophistication that God has provided us, such as digital estate planning, smart contracts, and advanced financial tools, inheritance distribution can be managed with even greater fairness, precision, and transparency, ensuring that every rightful heir receives their due. These advancements do not merely meet the Quranic requirements but elevate them, embodying the spirit of divine justice more fully than was possible in the past. This demonstrates that the Quran provides the framework and guiding principles for legal matters while leaving it to human reasoning and wisdom to determine the best means of implementation rather than adhering rigidly to mimetics.

Another example can be seen in the command to write down and witness financial transactions (Quran 2:282). This serves as the minimum requirement for such actions. While in the past, this required physical scribes to be present and manually document the transaction, today, digital banking systems, electronic contracts, and blockchain technology can ensure every transaction is recorded, verifiable, and protected, far exceeding the minimum requirement set by the Quran. Receipts, online statements, and automated records serve as innumerable witnesses, fulfilling the Quran’s requirements in a modern, efficient manner. This demonstrates how reasoning allows believers to preserve the intent of a law while adapting its implementation to current realities.

A similar application can be seen in legal testimony and the role of witnesses in criminal and financial cases. The Quran mandates the presence of witnesses in cases such as adultery to prevent false accusations, as well as in matters like wills and financial transactions. In the past, fulfilling this requirement depended on the physical presence of witnesses, relying solely on human memory and testimony. Today, digital recordings, video surveillance, and forensic evidence allow for a far more accurate and impartial record, effectively meeting the minimum requirement set by the Quran while eliminating the risks of bias, forgetfulness, or manipulation. By applying a reasoning, it becomes clear that the Quran’s intent is to uphold due process and safeguard against false accusations, not to rigidly insist on physically present human witnesses when more reliable and verifiable forms of evidence are available.

In matters of fair wages and employment (Quran 11:85), the Quran commands that people should be paid equitably and in full. In the past, this required immediate payments, calibrated scales, and written and witnessed agreements, but today, digital payroll systems, automated bank deposits, and instant transactions ensure that wages are tracked, documented, and protected. The spirit of the law remains intact, even though the implementation method has changed with dramatic improvements toward fairness and efficiency. This adaptation reflects how logic and reason allows Quranic guidance to evolve alongside societal advancements while maintaining its ethical foundation.

Justice and due process, which the Quran emphasizes in Quran 5:8, can also be strengthened through modern innovations. Today, legal decisions are supported by forensic evidence, digital case files, and legal reviews that ensure accuracy and fairness in judicial rulings. While the Quran commands believers to uphold justice and sets the boundaries for the limits, reasoning enables us to implement this principle in more reliable and sophisticated ways, aligning with the Quran’s intent rather than limiting justice to 7th-century legal procedures.

These examples illustrate that the Quran’s legal rulings are not static rules that cannot scale with time and technology but adaptable principles designed to be interpreted and implemented in ways that meet the minimum requirements set by the Quran while maximizing their original intent and spirit of the law. Reasoning allows believers to preserve the essence of Quranic rulings while ensuring their relevance in a changing world, reinforcing the Quran’s wisdom as a timeless guide rather than a rigid rulebook frozen in time.

Manāsik (Ritual Acts of Worship)

However, the only exception to when mimetics overtake reason is in the case of the manāsik (ritual acts of worship), which are meant to be mimetic. Salat (prayer), Zakat (charity), fasting, and Hajj (pilgrimage) are divine practices where the form and actions are to be perfectly preserved and explicitly done as commanded. Nevertheless, even in these cases, God provides stipulations for when ideal imitation is not possible. For example, the Quran permits praying while walking or riding (2:239) and allows missed fasts to be substituted or compensated by feeding the poor (2:184). These allowances reinforce that even mimetic practices are not absolute but adaptable to necessary circumstances.

Conclusion

This distinction between reasoning and mimetic approaches highlights a critical misinterpretation within Sunni tradition. The idea that righteousness is tied to replicating the prophet’s personal habits misses the Quran’s deeper emphasis on wisdom, justice, and moral reasoning. The Quran gives basic principles and sets limits (ḥudūd)—either defining a minimum (floor) or a maximum (ceiling) of what is permitted—but within these boundaries, humans are expected to apply their best judgment. This requires applying logic and reason, where the laws provide principles, not exhaustive details.

Understanding this distinction challenges the traditional Sunni paradigm. Rather than striving to mirror the prophet’s lifestyle in minute details based on unverifiable Hadith, true faith lies in understanding the principles behind divine law and applying them thoughtfully. Rituals serve as structured acts of devotion, but laws are meant to guide human conduct with flexibility, allowing for different contexts and circumstances. This perspective shifts religious engagement from blind imitation to thoughtful application, aligning more closely with the Quran’s intended balance between divine limits and human agency.

Related Articles:

Hadith regarding imitating the prophet.

- “Misquoting Muhammad,” Jonathan Brown, p. 44 & Abu Talib al-Makki, Qut al-qulub, 1:177 ↩︎

2 thoughts on “Hermeneutics: Mimetics vs. Reason”