Historically, both Christianity and traditional Islam have grappled with the tension between their foundational scriptures and the later traditions that emerged within their communities. Both faiths began with firm proclamations of strict monotheism with the declaration that there is no god but God. Yet, over time, scholars and theologians in both religions were compelled to devise intricate and often ingenious theological frameworks to reconcile their polytheistic traditions with their scriptural message of monotheism. This culminated with Christians and Sunni Muslims each fabricating claims to avoid being called polytheists. Christians claimed Jesus was God, and Sunnis claimed Hadith were divine inspiration (wahi).

Christian Dilemma: God or Jesus

Jesus and his immediate followers were devout Jews who adhered strictly to the commandments of the Torah, particularly the Shema, which declares:

“Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one.” 5 and you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. 6 And these words which I command you this day shall be upon your heart; 7 and you shall teach them diligently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise. 8 And you shall bind them as a sign upon your hand, and they shall be as frontlets between your eyes. 9 And you shall write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates.

This foundational monotheistic creed shaped their understanding of God as a singular, indivisible deity. Jesus himself reaffirmed this truth in Mark 12:29, underscoring the continuity of his teachings with the Torah. However, as Christianity spread beyond its Jewish roots, the faith encountered Greco-Roman Gentiles steeped in polytheistic traditions. These converts viewed Jesus as more than a human prophet, often interpreting his nature through the lens of their cultural worldview, which was accustomed to hierarchies of divine beings and emanations. For many, Jesus became a “lesser god” or a “second god,” aligning more closely with their pagan sensibilities than with the strict monotheism of the Torah.

This divergence gave rise to various theological innovations. Figures like Marcion of Sinope (c. 85–160 CE) outright rejected the Hebrew Scriptures and posited that the God of the Torah was distinct from the “higher” God revealed by Jesus. Marcion’s attempt to sever Christianity from its Jewish roots was condemned as heretical, but his influence highlighted the growing discomfort among Gentile Christians with reconciling Jesus’ divinity with the Torah’s monotheism.

Others, like Justin Martyr (c. 100–165 CE), sought middle ground by describing Jesus as a second god—a subordinate, divine intermediary—drawing heavily from Hellenistic philosophical concepts. Similarly, Origen (c. 184–253 CE) portrayed Jesus as a “lesser God” while maintaining his eternal nature. Such attempts at compromise ultimately fell short of true monotheism but allowed Gentile Christians to elevate Jesus’ status without fully embracing polytheism.

Church Fathers such as Justin Martyr (c. 100–165 CE) and Origen (c. 184–253 CE) proposed intermediary roles for Jesus. Justin Martyr described Jesus as the Logos, subordinate to the Father but divine in nature, reflecting Hellenistic ideas of divine emanation. Origen similarly held that Jesus was “a lesser God” than the Father, albeit eternal. Such views fell far short of monotheism but accommodated Jesus’ divinity.

Other theological responses, such as modalism, attempted to address these contradictions by suggesting that Jesus was merely a manifestation or mode of God rather than a distinct person. Advocates like Sabellius (c. 215–220 CE) argued that Jesus was essentially God appearing in a different form, while figures like Paul of Samosata (c. 260–272 CE) viewed Jesus as a human adopted by God and made a vessel for divine presence. These interpretations were different attempts to try to affirm Jesus’ divinity while avoiding outright polytheism, but they often introduced confusion and doctrinal instability.

The Arian controversy of the fourth century brought this theological tension to a head. Arius argued that Jesus, while divine, was a created being distinct and subordinate to the Father, emphasizing the human limitations Jesus himself acknowledged (e.g., John 14:28: “The Father is greater than I”). However, opponents like Athanasius of Alexandria contended that Arianism undermined the unity of the Church and the doctrine of salvation, which required Jesus to be both fully divine and fully human. Additionally, Arianism still had the issue of two distinct divine beings.

Ultimately, the doctrine of the Trinity emerged as the dominant solution, driven largely by political and ecclesiastical pressures. The First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, convened by Emperor Constantine, rejected Arianism and declared that Jesus was “of the same substance” (homoousios) as the Father. This decision marked a pivotal step toward solidifying Trinitarian theology. The Council of Constantinople in 381 CE further developed this framework, affirming the Holy Spirit’s divinity and codifying the doctrine of one God in three persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Athanasian Creed (c. 500 CE) left no room for dissent, declaring that all three persons were co-equal, co-eternal, and co-substantial and that any deviation from this belief was heretical.

What began as an effort to elevate Jesus’ status while preserving monotheism ultimately led to a profound distortion of biblical truth. The Trinity provided a theological structure that reconciled the polytheistic inclinations of Gentile Christians with their desire to align with the monotheism of the Torah. By collapsing the distinctions within the Godhead into a single essence, the doctrine gave the illusion of monotheism while accommodating the worship of multiple divine persons. This framework allowed its adherents to feel justified in their beliefs, even as they blurred the line between monotheism and idolatry, fulfilling the Quranic warning:

[5:73] Pagans indeed are those who say that GOD is a third in a trinity. There is no god except the one god. Unless they refrain from saying this, those who disbelieve among them will incur a painful retribution.

لَّقَدْ كَفَرَ ٱلَّذِينَ قَالُوٓا۟ إِنَّ ٱللَّهَ ثَالِثُ ثَلَـٰثَةٍ وَمَا مِنْ إِلَـٰهٍ إِلَّآ إِلَـٰهٌ وَٰحِدٌ وَإِن لَّمْ يَنتَهُوا۟ عَمَّا يَقُولُونَ لَيَمَسَّنَّ ٱلَّذِينَ كَفَرُوا۟ مِنْهُمْ عَذَابٌ أَلِيمٌ

Sunni Dilemma: Quran or Hadith

Sunni Islam, like early Christianity, faced a theological challenge of reconciling a secondary source of authority with the core tenets of its faith. However, while Christianity grappled with the divinity of Jesus, Sunni Islam faced the question of the religious authority of the Hadith and Sunnah—actions and sayings falsely attributed to the Prophet Muhammad—compiled centuries after his death.

The Quran is unequivocal in asserting itself as the sole source of divine law, explicitly forbidding reliance on any other texts for judgment in religious matters. The Quran repeatedly emphasizes its completeness and sufficiency:

[25:1] Most blessed is the One who revealed the Statute Book to His servant, so he can serve as a warner to the whole world.

[6:114] Shall I seek other than GOD as a source of law, when He has revealed to you this book fully detailed? Those who received the scripture recognize that it has been revealed from your Lord, truthfully. You shall not harbor any doubt.

[6:115] The word of your Lord is complete, in truth and justice. Nothing shall abrogate His words. He is the Hearer, the Omniscient.

[6:116] If you obey the majority of people on earth, they will divert you from the path of GOD. They follow only conjecture; they only guess.

The Quran informs us that if we take commands from another entity over what God commanded us, such actions would constitute setting up another partner with God.

[6:121] Do not eat from that upon which the name of GOD has not been mentioned, for it is an abomination. The devils inspire their allies to argue with you; if you obey them, you will be idol worshipers.

[9:31] They have set up their religious leaders and scholars as lords, instead of GOD. Others deified the Messiah, son of Mary. They were all commanded to worship only one god. There is no god except He. Be He glorified, high above having any partners.

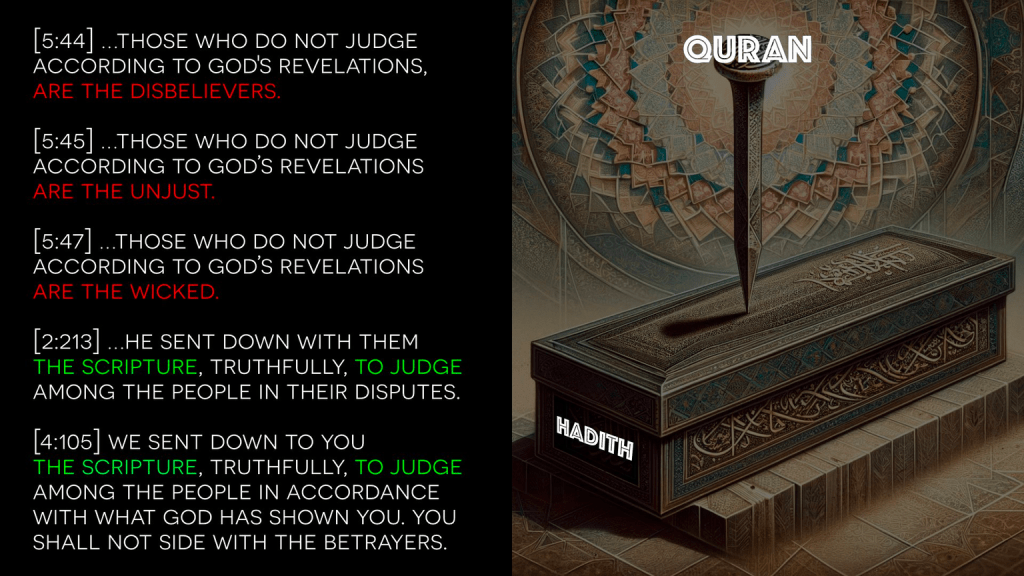

Additionally, the Quran is very clear that anyone who judges other than God’s revelations are disbelievers, unjust, and wicked.

[5:44] We have sent down the Torah, containing guidance and light. Ruling in accordance with it were the Jewish prophets, as well as the rabbis and the priests, as dictated to them in GOD’s scripture, and as witnessed by them. Therefore, do not reverence human beings; you shall reverence Me instead. And do not trade away My revelations for a cheap price. Those who do not rule in accordance with GOD’s revelations, are the disbelievers.

[5:45] And we decreed for them in it that: the life for the life, the eye for the eye, the nose for the nose, the ear for the ear, the tooth for the tooth, and an equivalent injury for any injury. If one forfeits what is due to him as a charity, it will atone for his sins. Those who do not rule in accordance with GOD’s revelations are the unjust.

[5:46] Subsequent to them, we sent Jesus, the son of Mary, confirming the previous scripture, the Torah. We gave him the Gospel, containing guidance and light, and confirming the previous scriptures, the Torah, and augmenting its guidance and light, and to enlighten the righteous.

[5:47] The people of the Gospel shall rule in accordance with GOD’s revelations therein. Those who do not rule in accordance with GOD’s revelations are the wicked.

As if the above verses are not definitive enough, the Quran also condemns Hadith multiple times in the Quran by name (See 4:87, 7:185, 18:6, 31:6, 52:34, 53:59, 68:44, 77:50.

[45:6] These are GOD’s revelations that we recite to you truthfully. In which Hadith other than GOD and His revelations do they believe?

[45:7] Woe to every fabricator, guilty.

[45:8] The one who hears GOD’s revelations recited to him, then insists arrogantly on his way, as if he never heard them. Promise him a painful retribution.

تِلْكَ ءَايَـٰتُ ٱللَّهِ نَتْلُوهَا عَلَيْكَ بِٱلْحَقِّ فَبِأَىِّ حَدِيثٍۭ بَعْدَ ٱللَّهِ وَءَايَـٰتِهِۦ يُؤْمِنُونَ

وَيْلٌ لِّكُلِّ أَفَّاكٍ أَثِيمٍ

يَسْمَعُ ءَايَـٰتِ ٱللَّهِ تُتْلَىٰ عَلَيْهِ ثُمَّ يُصِرُّ مُسْتَكْبِرًا كَأَن لَّمْ يَسْمَعْهَا فَبَشِّرْهُ بِعَذَابٍ أَلِيمٍ

Despite these clear prohibitions, Sunni Islam gradually elevated the status of Hadith, resulting in its inclusion as a source of divine guidance alongside the Quran. This transformation was not immediate but unfolded over centuries, reflecting significant shifts in Islamic jurisprudence and theology.

The earliest generations of Muslims, including the Rightly Guided Caliphs, exhibited a strong commitment to the Quran as the sole source of legislation. Not only did they not make any effort to catalog or preserve Hadith, but they actually had deliberate campaigns to burn, destroy, and stop the spread of Hadith. This is most notably seen in the history of Umar ibn al-Khattab, who emphasized strict adherence to the Quran. Umar viewed the Quran as the sole source of divine legislation and rejected widespread reliance on Hadith.

Historical accounts indicate that Umar actively discouraged the compilation and reliance on Hadith, fearing it would divert attention from the Quran. Umar believed that the Quran was entirely sufficient for guiding the Muslim community, and he reportedly took drastic measures to destroy Hadith and to preserve the Quran’s primacy. For example, he imprisoned people for spreading Hadith, he did not allow Abu Hurairah to spread any Hadith, he did not let the companions leave Medina because he didn’t want them spreading hadith, and when his armies went on their campaigns, he forbid them to spread Hadith.

However, as the Muslim community expanded and faced new practical and legal challenges, scholars began to turn to Hadith for supplementary rulings. This process began cautiously, with early jurists like Abu Hanifa (d. 767 CE), founder of the Hanafi school, treating Hadith as secondary to reason and analogical reasoning (qiyas), ensuring the Quran’s supremacy.

A significant shift occurred with Malik ibn Anas (d. 795 CE), founder of the Maliki school, who incorporated Hadith into his legal methodology. However, Malik relied primarily on the practices of the people of Medina, which he regarded as the closest approximation of the Prophet’s Sunnah. While he used Hadith, he did not yet regard it as divinely inspired or co-equal with the Quran. Additionally, he refused to have his compilation of Hadith as the defacto book of legal ruling in the Muslim lands even when it was requested by the Caliph.

The elevation of Hadith reached a turning point with Muhammad ibn Idris al-Shafi‘i (d. 820 CE), who systematically argued that the Hadith was divine inspiration (wahi). Al-Shafi‘i interpreted the Quranic term Hikma (“wisdom”) as a reference to the Hadith, asserting that it was on equal footing to the Quran. His arguments gave Hadith a formal status as a source of law, effectively pairing it with the Quran as divinely inspired guidance.

This trend culminated with Ahmad ibn Hanbal (d. 855 CE), founder of the Hanbali school, who treated Hadith as the ultimate authority in religious matters. For Ibn Hanbal, authentic Hadith could even override interpretations of the Quran, solidifying its place as a co-equal source of divine law. This marked the point at which Hadith became indispensable to Sunni jurisprudence.

The integration of Hadith reached such extremes that later scholars made audacious claims about its necessity. Statements attributed to prominent figures such as al-Awza’i and Yahya ibn Abi Kathir reflect this perspective:

“The Quran needs the Sunnah more than the Sunnah needs the Quran.”

“The Sunnah came to rule over the Quran; it is not the Quran that rules over the Sunnah.”

Thus, Sunni Islam’s elevation of Hadith represents a significant departure from the Quran’s explicit prohibitions. By granting Hadith divine status, Sunni scholars attempted to elevate their traditions to rival the Quran, but in doing so, they introduced an authority that arguably undermines the Quran’s claim to completeness and exclusivity as the word of God.

Conclusion:

The histories of Christianity and Sunni Islam reveal a striking parallel: the struggle to reconcile the foundational monotheism of their scriptures with the inclinations towards idol worship from its followers. For Christians, the challenge was how to elevate Jesus to divine status without violating the Shema’s proclamation of God’s oneness. For Sunni Muslims, the dilemma was how to elevate the Hadith and Sunnah as sources of religious authority without undermining the Quran’s explicit assertion of its completeness and exclusivity as the sole source of divine law.

In both cases, the resolution followed a similar pattern of theological innovation. Christians resolved the tension by formulating the doctrine of the Trinity, declaring that Jesus and the Father were co-equal, co-eternal, and of the same essence, thereby masking the introduction of a secondary divine figure under the guise of monotheism. Similarly, Sunni Muslims falsely elevated the Hadith and Sunnah to a level of divine inspiration, effectively making them co-equal to the Quran in authority. Thus, both Christianity and Sunni Islam each took centuries to create frameworks that effectively blurred the lines between monotheism and idolatry, allowing them to feel justified in each of their respective forms of idol worship.

Related Articles: