It is well understood that Umar had a strong position against people spreading Hadith and traditions attributed to the prophet and strongly enjoined the people to follow the Quran alone.

Narrated ‘Ubaidullah bin `Abdullah: Ibn `Abbas said, “When the ailment of the Prophet (ﷺ) became worse, he said, ‘Bring for me (writing) paper and I will write for you a statement after which you will not go astray.’ But `Umar said, ‘The Prophet is seriously ill, and we have got Allah’s Book with us, and that is sufficient for us.’ But the companions of the Prophet (ﷺ) differed about this, and there was a hue and cry. On that, the Prophet (ﷺ) said to them, ‘Go away (and leave me alone). It is not right that you should quarrel in front of me.” Ibn `Abbas came out saying, “It was most unfortunate (a great disaster) that Allah’s Messenger (ﷺ) was prevented from writing that statement for them because of their disagreement and noise.

حَدَّثَنَا يَحْيَى بْنُ سُلَيْمَانَ، قَالَ حَدَّثَنِي ابْنُ وَهْبٍ، قَالَ أَخْبَرَنِي يُونُسُ، عَنِ ابْنِ شِهَابٍ، عَنْ عُبَيْدِ اللَّهِ بْنِ عَبْدِ اللَّهِ، عَنِ ابْنِ عَبَّاسٍ، قَالَ لَمَّا اشْتَدَّ بِالنَّبِيِّ صلى الله عليه وسلم وَجَعُهُ قَالَ ” ائْتُونِي بِكِتَابٍ أَكْتُبُ لَكُمْ كِتَابًا لاَ تَضِلُّوا بَعْدَهُ ”. قَالَ عُمَرُ إِنَّ النَّبِيَّ صلى الله عليه وسلم غَلَبَهُ الْوَجَعُ وَعِنْدَنَا كِتَابُ اللَّهِ حَسْبُنَا فَاخْتَلَفُوا وَكَثُرَ اللَّغَطُ. قَالَ ” قُومُوا عَنِّي، وَلاَ يَنْبَغِي عِنْدِي التَّنَازُعُ ”. فَخَرَجَ ابْنُ عَبَّاسٍ يَقُولُ إِنَّ الرَّزِيَّةَ كُلَّ الرَّزِيَّةِ مَا حَالَ بَيْنَ رَسُولِ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم وَبَيْنَ كِتَابِهِ.

Sahih al-Bukhari 114

https://sunnah.com/bukhari:114

Additionally, it is reported that during his reign as Caliph, Umar did not allow the prophet’s companions to travel freely without his permission because he did not want them to propagate Hadith. It wasn’t until the reign of Uthman that this ban was lifted, and the companions were allowed to emigrate to some of the newly Muslim-conquered regions.

In Tadhkirat al-huffaz, al-Dhahabi reported from Shu’bah, from Sa’id ibn Ibrahim from his father, that Umar detained Ibn Mas’ud, Abu al-Darda’, and Abu Mas’ud al-Ansari, saying to them: You have narrated hadith abundantly from the Messenger of Allah. It is reported that he had detained them in Medina, but they were set free by Uthman.

Ibn Sa’d, and Ibn Asakir reports from Mahmud ibn Labid that he said: I heard Uthman ibn Affan addressing people from over the pulpit: It is unlawful for everyone to narrate any hadith he never heard of during the time of Abu Bakr and that of Umar. Verily that which made me abstain from narrating from the Messenger of Allah was not to be among the most conscious of his Companions, but I heard him declaring: “Whoever ascribing to me something I never said, he shall verily occupy his (destined) abode in Fire.”

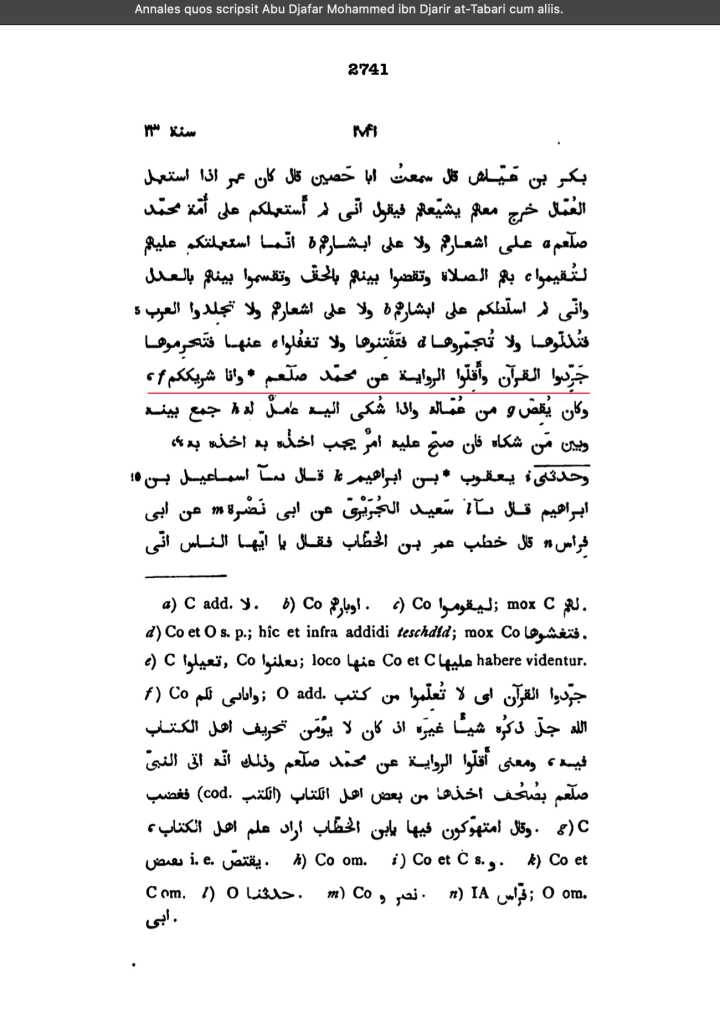

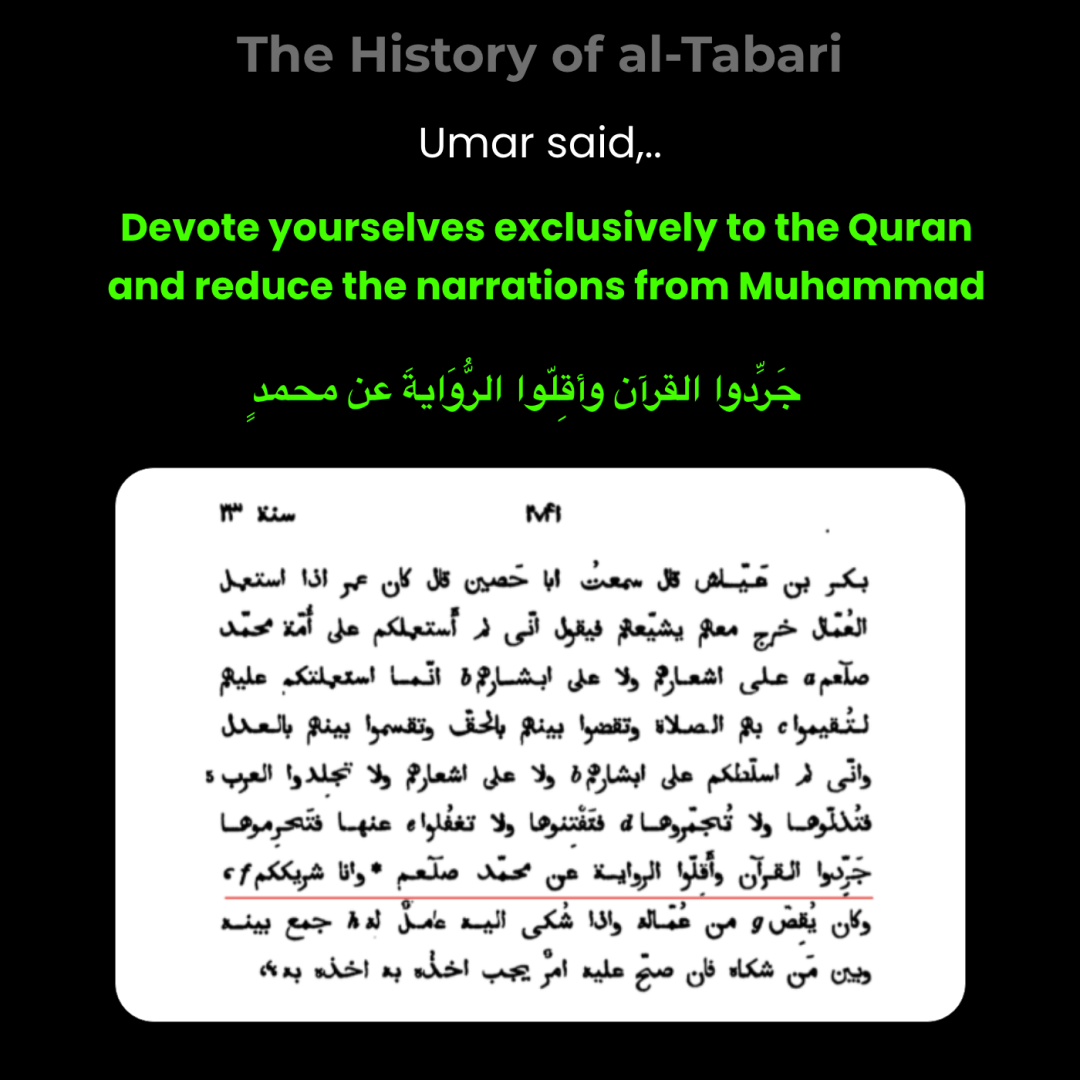

Also, we find the following Hadith in The History of al-Tabari, Vol. XIV p. 108, and from the Leiden edition of al-Tabari titled “Annales quos scripsit Abu Djafar Mohammed ibn Djarir at-Tabari” Vol III, p. 188.

According to Abu Kurayb – Abu Bakr b. Ayyash – Abu Hasin: Whenever ‘Umar appointed his governors, he would go out with them to bid them farewell, saying, “I have not appointed you governor over Muhammad’s community with limitless authority. I have made you governor over them only to lead them in prayer, to make decisions among them based on what is right, and to distribute (the spoils) among them justly. I have not given you limitless authority over them.

Do not flog the Arabs and humiliate them; do not keep them long from their families and bring temptation upon them; do not neglect them and cause them deprivation. Be exclusively devoted to the Qur’an, and diminish the annotations of Muhammad, and I am your partner.”

He would also allow vengeance to be taken on his governors. If there was a complaint against a governor, he would bring together the governor and the complainant. If there was a genuine case against (the governor) for which punishment was obligatory, he would punish him.

Here is the Arabic expression, that I wanted to emphasize (underlined in red above):

جَرِّدوا القرآن وأَقِلّوا الرواية محمّد صلعم وانا شريككم

Here is the word-by-word breakdown for this expression.

| جَرِّدوا | jarridoo | Be exclusively devoted [you all] |

| القرآن | al-Qur’an | the Quran, |

| وأَقِلّوا | wa-aqalluu | and diminish [you all] |

| الرواية | al-rawaaya | the transmissions (of) |

| محمد | Muhammad | Muhammad, |

| صلعم | salla Allahu `alayhi wa sallam | peace and blessings be upon him, |

| وانا | wa-ana | and I am |

| شريككم | shareekukum | your partner. |

The root letters of the word جَرِّدوا in Arabic are “ج ر د” (j, r, d), which have the basic meaning of “to strip, to remove, to take off.” When used in the command form, it means to “devote or apply oneself diligently and exclusively, and not to be diverted therefore by any other thing.” Therefore, in this sentence, Umar was commanding the people to be exclusively devoted to the Quran.

Therefore, this expression ” جَرِّدوا القرآن وأَقِلّوا الرواية محمّد ” is stating to the people that they should “Be exclusively devoted to the Quran, and diminish the commentary of Muhammad.” If people do this, then Umar would be their partner in this matter.

This again emphasizes Umar’s devotion to people following the Quran alone during his reign after the prophet’s death. This shows that Umar advocated for the Quran alone and against the dissemination of Hadith. Ironically, if someone made this statement today, they would be called a heretic by the Muslim masses.

In the book Ta’wil Mukhtalif al-Hadith by Ibn Qutaybah (828-890 CE/213-276 AH), on page 70 of the Annotated Translation, Ibn Qutaybah says the following regarding ‘Umar’s view on Hadith transmission:

…’Umar, who was abrasive against whoever transmitted numerous ahadith or reported information related to judicial judgment without any witness. He used to order (the narrators) to reduce the number of narrations so that the masses will not be confused or corrupted by falsehood.

In the book “Imam Abu Hanfiah Life and Work” by Shibli Nomani, on pages 131-132, it states,

“Al-Dhahabi writes in the Tabaqat al-Huffaz that Umar, from a fear that narrators might ascribe incorrect traditions to the prophet, always used to tell them to narrate as few traditions as possible. While sending a delegation of Ansar to Kufah, he instructed them as follows: “In Kufah you will meet a group of people who reciate the Qur’an in a voice full of emotion. On hearing of your arrival they will come to you, eager to listen to traditions of the Prophet from you. Be careful not to narrate to them too many traditions.

Similarly when sending a number of Companions to Iraq, ‘Umar went part of the way with them to see them off. “Do you know,” he asked them, “why I am accompanying you part of the way?” “In order to honour us,” they replied. “That is so,” said ‘Umar, “but there is also another reason. I want to tell you that the people of the country to which you are going are fond of reading the Qur’an. Try not to entagle them in traditions but narrate very few traditions from the Prophet.” When the Companions arrived at Qurzah, the inhabitants came to see them and requested them to narrate traditions; but they declined to do so, excusing themselves by saying that they had been forbidden by the caliph.

Abu Hurayrah, asked by Abu Salamah whether he used to narrate traditions as freely in ‘Umar’s time as he was then doing, replied, “No, for if I had tried, ‘Umar would have had me whipped.”

Umar Burns Hadith and Compares it to Mishna

The following narration in Ibn Saad’s “Tabaqat” (Volume 5) includes another story about Umar and his stance on Hadith. This account is attributed to Al-Qasim ibn Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr al-Siddiq (d. 106 AH). Al-Qasim, the grandson of Abu Bakr (one of Prophet Muhammad’s closest companions and the first Caliph), was approached by his student, Abd Allah ibn al-Ala’ (d. 164 AH), with a request to dictate Hadith. Al-Qasim, however, refused to do so and supposedly stated:

“the Hadith multiplied during the time of Umar; then he called on the people to bring them to him, and when they brought them to him, he ordered them to be burned.” Afterward, he said, ‘a Mishna like the Mishna of the People of the Book,’ (mathna’a ka mathna’at ahl al-Kitab).”

In the above narration, not only does Umar burn Hadith attributed to the prophet, but he compares it to the Mishna, the Oral Law of the Children of Israel. This is the folly of the Muslim ummah that they set up a secondary book of law beside the Quran, just like the Children of Israel have done to the Torah in the past.

Final Thoughts

Naturally, upholding the Quran alone aligns with the message in the Quran as it should be the only source of religious law for the true followers of Muhammad.

[6:112] We have permitted the enemies of every prophet—human and jinn devils—to inspire in each other fancy words, in order to deceive. Had your Lord willed, they would not have done it. You shall disregard them and their fabrications.

[6:113] This is to let the minds of those who do not believe in the Hereafter listen to such fabrications, and accept them, and thus expose their real convictions.

وَكَذَٰلِكَ جَعَلْنَا لِكُلِّ نَبِيٍّ عَدُوًّا شَيَاطِينَ الْإِنْسِ وَالْجِنِّ يُوحِي بَعْضُهُمْ إِلَىٰ بَعْضٍ زُخْرُفَ الْقَوْلِ غُرُورًا وَلَوْ شَاءَ رَبُّكَ مَا فَعَلُوهُ فَذَرْهُمْ وَمَا يَفْتَرُونَ

وَلِتَصْغَىٰ إِلَيْهِ أَفْئِدَةُ الَّذِينَ لَا يُؤْمِنُونَ بِالْآخِرَةِ وَلِيَرْضَوْهُ وَلِيَقْتَرِفُوا مَا هُمْ مُقْتَرِفُونَ

[6:114] Shall I seek other than GOD as a source of law, when He has revealed to you this book fully detailed? Those who received the scripture recognize that it has been revealed from your Lord, truthfully. You shall not harbor any doubt.

[6:115] The word of your Lord is complete, in truth and justice. Nothing shall abrogate His words. He is the Hearer, the Omniscient.

أَفَغَيْرَ اللَّهِ أَبْتَغِي حَكَمًا وَهُوَ الَّذِي أَنْزَلَ إِلَيْكُمُ الْكِتَابَ مُفَصَّلًا وَالَّذِينَ آتَيْنَاهُمُ الْكِتَابَ يَعْلَمُونَ أَنَّهُ مُنَزَّلٌ مِنْ رَبِّكَ بِالْحَقِّ فَلَا تَكُونَنَّ مِنَ الْمُمْتَرِينَ

وَتَمَّتْ كَلِمَتُ رَبِّكَ صِدْقًا وَعَدْلًا لَا مُبَدِّلَ لِكَلِمَاتِهِ وَهُوَ السَّمِيعُ الْعَلِيمُ

[6:116] If you obey the majority of people on earth, they will divert you from the path of GOD. They follow only conjecture; they only guess.

وَإِنْ تُطِعْ أَكْثَرَ مَنْ فِي الْأَرْضِ يُضِلُّوكَ عَنْ سَبِيلِ اللَّهِ إِنْ يَتَّبِعُونَ إِلَّا الظَّنَّ وَإِنْ هُمْ إِلَّا يَخْرُصُونَ

The following excerpts are from the book “Hadith as Scripture: Discussions on the Authority of Prophetic Traditions in Islam” by Aisha Y. Musa (pp. 23-28)

The first story Ibn Sa’d narrates about ‘Umar’s attitude toward the recording of the Hadith occurs in the section where he recounts his appointment as Caliph (Dhikr istikhlaf ‘Umar). He cites a story from Sufyan ibn ‘Uyayna (d. 198 AH), on the authority of al-Zuhri that “’Umar wanted (arada) to write the Traditions (al–sunan), so he spent a month praying for guidance; and afterward, he became determined to write them. But then he said: ‘I recalled a people who wrote a book, then they dedicated themselves to it (aqbalu ‘alaihi) to it and neglected the Book of God (wa-taraku Kitab Allah). ‘”

One argument that could be used against accepting this story is that it is mursal—its isnād is missing a direct link between al-Zuhrī (b. c. 50/670) and ʿUmar (d. 22/644)—and should therefore be discounted. However, Ibn Saʿd has not seen fit to exclude it on that basis and both al-Shāfiʿī and Ibn Qutayba are known to have accepted mursal reports from trustworthy individuals.

The wording of this story is very direct and leaves no doubt as to what ʿUmar feared might happen if he were to commit the Traditions (al-sunan) of the Prophet to writing: that, like people before them, Muslims might turn their attention to that book and neglect the Qurʾān. Who those people were is not specified in this story. However, the other stories found elsewhere in the Ṭabaqāt are equally clear in wording and give additional detail.

The next story that Ibn Saʿd recounts about the Commander of the Faithful and his attitude toward the Ḥadīth is found in volume five of the Ṭabaqāt. It is related on the authority of al-Qāsim ibn Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr al-Ṣiddīq (d. 106 AH)—the grandson of Abū Bakr, another of Muḥammad’s closest companions and the first of the rightly guided Caliphs who led the Muslim community after his death. When al-Qāsim was asked by his student ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-ʿAlāʾ (d. 164 AH) to dictate Ḥadīth, he refused, saying, “the Ḥadīth multiplied during the time of ʿUmar; then he called on the people to bring them to him, and when they brought them to him, he ordered them to be burned. Afterward, he said, ‘a Mishna like the Mishna of the People of the Book,’ (mathnaʾa ka mathnaʾat ahl al-Kitāb).” “From that day on,” ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-ʿAlāʾ continues, “al-Qāsim forbade me to write Ḥadīth.” As in the first story, what disturbs ʿUmar is the writing of a book that will compete with the Book of God. He compares the written Ḥadīth with the Mishna of the People of the Book. In Judaism, the Mishna serves much the same function that the Ḥadīth have come to serve in Islam. It is a codification of the Oral Law and contains rulings related to the details of ritual purity, prayer, marriage, divorce, and so on. The Mishna and the Gemara together make up the Talmud, which is the most important book in Judaism besides the Torah.

However, ʿUmar is credited with objecting to not only the writing of the Ḥadīth, but also to transmitting them. Perhaps the strongest and most compelling story about ʿUmar’s attitude toward Prophetic traditions is that found in volume six of the Ṭabaqāt. Here, Ibn Saʿd relates the story of ʿUmar’s instructions to a delegation of companions that he is sending to the region of Kūfa to serve as administrators. He orders them not to distract the people from the Qurʾān with the transmission of Ḥadīth. Again, the wording attributed to ʿUmar is significant:

“lā tuṣaddidūhum bil-aḥādīth fa-tashghalūnahum jarridū al-Qurʾān wa-aqillū al-riwāyāt ʿan rasūl Allāh”

(Do not distract them with the Ḥadīths, and thus engage them! Bare the Qurʾān and spare the narration from God’s Messenger!).

Several things are important about this particular story.

The first issue concerns the wording, and the second concerns one of the transmitters of the story. ʿUmar is giving strong and direct commands in this story: “la taṣaddidūhum bil-aḥādīth fa-tashghalūnahum” (Do not distract them with the Ḥadīths, and thus engage them!). ʿUmar follows this up with another equally direct order that deserves careful attention: “jarridū al-Qurʾān.” The Arabic verb jarrid is the imperative of the second form of j-r-d, literally meaning to make something bare. According to Lisān al-ʿArab, when used with the Qurʾān as its object, as it is in this story, it means not to clothe the Qurʾān with anything. In the Lisān, Ibn Manẓūr specifically quotes Ibn ʿUyayna (d. 198 AH), from whom Ibn Saʿd relates this story, as saying that jarridū al-Qurʾān means not to clothe the Qurʾān with Ḥadīths (aḥādīth) of the People of the Book. However, in this case, ʿUmar’s next words indicate the source of the stories (al-aḥādīth) with which the Qurʾān should not be clothed—al-riwāyāt ʿan rasūl Allāh—narration from God’s messenger. In reporting this story from Ibn ʿUyayna, Ibn Saʿd does not indicate that Ibn ʿUyayna offered other than a literal understanding of ʿUmar’s words.

Yet ʿUmar clearly has not strictly forbidden such narration: “jarridū al-Qurʾān wa aqillū al-riwāyāt ʿan rasūl Allāh” (Bare the Qurʾān and be sparing with narration from God’s Messenger.). It is not talking about the Messenger or what the Messenger may have said that troubles ʿUmar. What troubles him is the possibility of generating something that would rival the Book of God. In the previous stories, ʿUmar’s concern was that writing down the Traditions would do so. In this story it is clear that he fears any narration of Prophetic Traditions will do the same thing.

Taken together, these stories indicate that writing and transmitting the Ḥadīth was a commonly accepted practice—it is only after careful consideration that ʿUmar rejects the idea of putting the Ḥadīth in writing, and then takes the drastic step of calling for and destroying what others had written of the Ḥadīth. This suggests that ʿUmar’s actions represent a radical departure from the prevailing norm. In that case, ʿUmar, in keeping with his image as the defender of God’s Book, is acting in response to something that is competing for status and authority with God’s Book.

If these stories truly represent ʿUmar’s attitude toward writing and transmitting Prophetic traditions, it could be argued that they represent his personal opinion and are not based on a command from the Prophet. However, there are two problems with this argument. First, it presupposes the acceptance of commands of the Prophet, beyond the Qurʾān, as binding, while that idea was still a matter of some debate when ʿAbd al-Razzāq and Ibn Saʿd were writing. Second, and more importantly, even if it is only ʿUmar’s personal opinion, it is still the basis for his objections to the transmission and writing of the Ḥadīth. According to these stories, ʿUmar strongly opposed both the writing and the transmission of Ḥadīth—not because he disapproved of writing or of sharing information, but because he feared that they would gain a status equal to or even greater than that of the Qurʾān itself. Even if these stories do not truly represent the attitude, commands, and actions of ʿUmar, they do represent him as the archetypal defender of God’s Book at a time when some people saw the Prophetic traditions as competing for status and authority with God’s Book.

Canonical and noncanonical, report ʿUmar’s concern about extra-Qurʾānic materials from the Prophet. The collections of Ḥadīth that eventually became canonized are not the earliest collections of Ḥadīth that have come down to us. An important earlier work is the Muṣannaf of ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Ṣanʿānī (d. 211/827). ʿAbd al-Razzāq reports both ʿUmar’s decision not to commit the Sunna to writing for fear that it will lead to a book to which people turn and leave the Book of God, and also a story in which ʿUmar gives this order to those he is sending out to govern. The details of the former story are nearly identical with minor but notable additions. However, the details of the latter differ more dramatically between the version reported by ʿAbd al-Razzāq and the version reported some two decades later by Ibn Saʿd. The story about ʿUmar abandoning the idea of committing the Sunna to writing recorded by ʿAbd al-Razzāq adds the statement that ʿUmar consulted the Prophet’s companions on the issue and that they encouraged him to do so. ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s version also ends with a dramatic statement attributed to ʿUmar. After recalling a previous people who wrote a book to which they dedicated themselves and for which they “left the Book of God,” ʿUmar is reported as saying, “wa-innī wallāhi lā ulabbis Kitāb Allāh bi-shayʾin abadan” (By God! I will never clothe the Qurʾān with anything). Looking back at the entry in Lisān al-ʿArab noted earlier in the discussion of the story related in the Ṭabaqāt, Ibn Manẓūr specifies that jarridū al-Qurʾān means not to clothe it with anything (lā tulabbisū bihi shayʾan). This addition suggests that the Ḥadīth will not only cause people to desert the Qurʾān, but that they may also somehow conceal it from them.

The details differ even more in the stories in which ʿUmar is quoted as ordering his provincial governors to “bare the Qurʾān.” In order to appreciate the differences, let us compare both stories in their entirety. First, Ibn Saʿd’s version:

We were headed toward Kūfa and ʿUmar accompanied us as far as Sirār. Then he made ablutions, washing twice, and said: “Do you know why I have accompanied you?” We said: “Yes, we are companions of God’s messenger (peace and blessings be upon him).” Then, he said: “You will be coming to a people of a town for whom the buzzing of the Qurʾān is as the buzzing of bees. Therefore, do not distract them with the Ḥadīths, and thus engage them. Bare the Qurʾān and spare the narration from God’s Messenger (peace and blessings be upon him)! Go and I am your partner.”

Now, the story as reported by ʿAbd al-Razzāq:

When ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb dispatched his provincial governors he stipulated: “Do not ride a workhorse; do not eat marrow; do not wear delicate clothing; do not bolt your doors against the needs of the people; and if you do any of these things, punishment will unquestionably befall you.” Then he accompanied them, and when he intended to return, he said: “I have not given you authority over the blood of Muslims, nor over their reputations, nor over their property; but I have sent you to establish Ṣalāt with them, and to divide their booty and judge among them fairly. Then, if anything is unclear to them, refer them to me. Indeed, do not beat the Arabs, so as to humiliate them, and do not detain them [the army at the frontier] so as to cause them strife, and do not exalt yourselves over them so as to dispossess them; bare the Qurʾān and spare the narration from the God’s Messenger (peace and blessings be upon him)! Go and I am your partner.”

The earlier story related by ʿAbd al-Razzāq is somewhat longer than the later story, containing a broad variety of orders. It is a list of commands and prohibitions that includes the command to “bare the Qurʾān and spare the narration from God’s Messenger.” However, the later story recorded by Ibn Saʿd does not contain any of the other orders found in the early version. Instead, it focuses on this particular order and includes detailed reasoning, in lyrical wording, on ʿUmar’s part: “You will be coming to the people of a town for whom the buzzing of the Qurʾān is as the buzzing of bees. Therefore, do not distract them with the Ḥadīth . . . .” The comparison of the recitation of the Qurʾān to the buzzing of bees suggests that the people are constantly occupied with the Qurʾān. The Ḥadīth are portrayed as something that may take their attention away from the Qurʾān. The idea that the Ḥadīth will distract people from the Qurʾān is central to the arguments against the Ḥadīth that we will see later in al-Khaṭīb al-Baghdādī’s Taqyīd al-ʿIlm, and in the modern arguments.

The increasing detail and elaboration that are evident in the stories reported about ʿUmar from ʿAbd al-Razzāq’s Muṣannaf and Ibn Saʿd’s Ṭabaqāt in the early and mid-third century AH, to al-Baghdādī’s Taqyīd al-ʿIlm in the mid-fifth century AH suggests that as the Ḥadīth gained greater authority and attention, those who opposed that authority developed and refined their own arguments.

ʿUmar also figures prominently in a story found in the canonical collections of the Ḥadīth. That story relates an incident that took place during the Prophet Muḥammad’s final illness. Several versions are recorded in the Ṣaḥīḥs of al-Bukhārī and Muslim, as well as in the Musnad of Aḥmad. In each version the central details of the story are the same: during Muḥammad’s final illness, he requests writing materials so that he can write something for the people to insure that they will not go astray. Seeing that fever had overcome the Prophet, ʿUmar is quoted as saying: “They have the Qurʾān, and the Book of God is enough for us.” These stories reinforce the idea that the Qurʾān is enough to keep the people from going astray. Furthermore, they move ʿUmar’s reported opposition to a written source other than the Qurʾān—even from the hand of the Prophet himself—back to the lifetime of the Prophet. Attributing the Prophet’s desire to write something (presumably other than the Qurʾān) that would keep people from going astray to his being overcome by fever implies that if he had been in control of his faculties, he would not have wanted to do this. As with the stories reported by Ibn Saʿd, it can be argued that these stories represent ʿUmar’s personal opinion, particularly since they also state that there was strong disagreement among the companions who were present at the time. However, here too, even if this is understood as ʿUmar’s personal opinion, the primary concern attributed to him is clear. He feels so strongly that the Qurʾān is sufficient as an authoritative source of guidance that he refuses the Prophet’s request for writing materials, reminding the Prophet that the people have the Qurʾān and that it is enough.

Probing the stories of ʿUmar’s response to the Prophet’s request, Kern says:

With ʿUmar’s declaration that the Book of God was “sufficient,” however, not only was Muḥammad’s importance for interpreting the revelation lessened, but the notion of his superiority in religious matters was also set aside henceforth, according to ʿUmar’s interpretation, the Book of God in itself would be entirely adequate . . . ʿUmar’s declaration that the Book of God was sufficient changed the conception of what the revelation was, however, just as much as it altered the conception of the Prophet’s role.

The change to which Kern is referring is a shift from “on-going, unpredictable, situation-specific revelation” to “a totality of eternally perfect revelation, or more precisely, the Revelation.” Once again, Kern’s assessment helps to make clear why ʿUmar is the ideal figure to find at the center of the disputes over the authority of the Ḥadīth. The nature of revelation and the role of the Prophet are at the heart of those disputes.

4 thoughts on “Umar Advocated Quran Alone”