One of the most frequently repeated objections to the Quran’s account of the golden calf concerns a single word: al-Sāmirī (ٱلسَّامِرِىُّ), “the Samarian.” Critics argue this constitutes a historical anachronism, since Samaria did not exist as a city until centuries after Moses. The objection appears straightforward: the Quran projects a later geographical identity backward into an earlier period, thereby betraying ignorance of Israelite chronology.

This objection rests on a category error. Al-Sāmirī is not a geographical designation but a retrospective moral one—a pattern consistent with the Quran’s method of naming figures according to what they inaugurate rather than when they live. Far from exposing confusion about dates, the term demonstrates theological precision: it names the wilderness instigator by the tradition his act ultimately produced. The first calf and the later kingdom of calves are not separate phenomena but expressions of the same rebellion, and both scriptures—Quran and Bible—testify to this continuity.

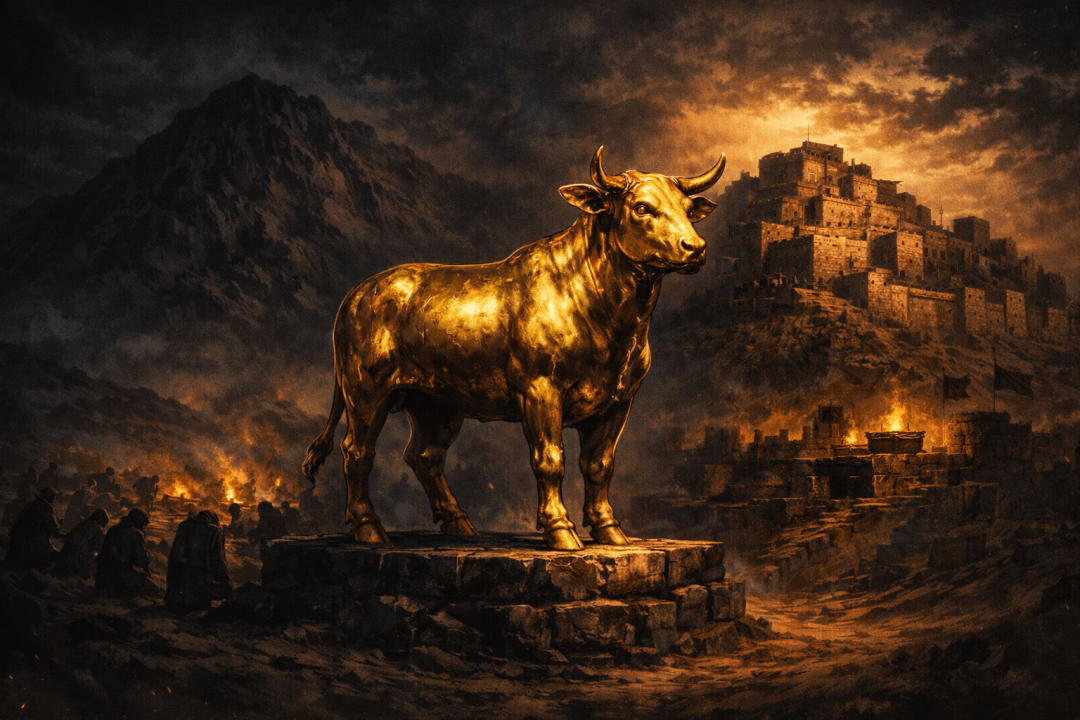

The Samarian in the Quran

Before examining how the Quran names this figure, we must first understand what it says about him. The Quranic narrative in Sura Ṭā Hā is theologically precise. Moses departs to receive divine instruction, only to find upon his return that his people have reverted to idol worship. The text immediately identifies causation:

[20:85] He said, “We have put your people to the test after you left, but the Samarian misled them.”

The Samarian is introduced not as background detail but as the causal agent of misguidance. When Moses returns, the people acknowledge this agency even while attempting to mitigate their own culpability:

[20:87] They said, “We did not break our agreement with you on purpose. But we were loaded down with jewelry, and decided to throw our loads in. This is what the Samarian suggested.”

The calf emerges—animated with sound, imbued by human projection with divine status:

[20:88] He (the Samarian) produced for them a sculpted calf, complete with a calf’s sound. They said, “This is your god, and the god of Moses.” Thus, he forgot.

Crucially, the Quran reframes the biblical account. Aaron is not a collaborator but a resisting voice:

[20:90] And Aaron had told them, “O my people, this is a test for you. Your only Lord is the Most Gracious, so follow me, and obey my commands.”

[20:91] They said, “We will continue to worship it, until Moses comes back.”

When confronted, Aaron explains his restraint as fear of fragmenting the community. Only then does Moses turn to the true instigator:

[20:95] He (Moses) said, “What is the matter with you, O Samarian?”

[20:96] He (the Samarian) said, “I saw what they could not see. I grabbed a fistful (of dust) from the place where the messenger stood, and used it (to mix into the golden calf). This is what my mind inspired me to do.”

The punishment is symbolic and final:

[20:97] He (Moses) said, “Then go, and, throughout your life, do not even come close. You have an appointed time (for your final judgment) that you can never evade. Look at your god that you used to worship; we will burn it and throw it into the sea, to stay down there forever.”

The narrative emphasizes personal agency in misguidance, the seductive power of tangible symbols, and the consequences of substituting visible power for obedience. What matters for the present argument is that nowhere does the Quran claim Samaria as a contemporary city. The designation functions differently.

Quran’s Method of Naming

The Quran consistently names figures not by chronological accident but by functional identity. Its concern is moral genealogy, not cartographic precision. This principle governs its entire onomastic theology.

Pharaoh is never given a personal name, despite Egyptian rulers being historically identifiable. The Quran is not interested in which Pharaoh opposed Moses, but in Pharaoh as archetype: the embodiment of political arrogance, false divinity, and conscious resistance to truth. Qaroon represents wealth absolutized into arrogance. Abu Lahab is stripped of his given name and permanently redefined by his opposition to revelation as Father of Flame. In each case, identity is assigned by function and outcome, not by birth certificate or regnal year.

Collective designations follow the same logic. The Quran speaks of the People of the Elephant, the People of the Canyon, and the People of Sheba without historical cataloguing. These names preserve memory through meaning. What matters is the defining act, not the coordinates.

Within this established pattern, al-Sāmirī functions identically. The Quran names the wilderness instigator according to the tradition his act ultimately produced. The calf does not end at Sinai; it becomes institutionalized in the Northern Kingdom, whose political and religious center is Samaria. The name identifies the trajectory of rebellion, not the address of the rebel. This is not geographical projection but theological compression—reading history forward with coherence.

The objection dissolves once the method is recognized. The Quran does not claim that Samaria existed in Moses’ time. It identifies the calf’s originator by his legacy, just as it identifies every other figure by what they represent in the unfolding drama of belief and rebellion.

Retrospective Naming in the Bible

The Quran’s method is not unique to its text but reflects a broader pattern in ancient Near Eastern and biblical literature. Understanding this context demonstrates that demanding strict chronological naming is itself anachronistic—it imposes modern historiographical expectations onto texts that operated according to different principles.

The Hebrew Bible itself employs retrospective terminology in its earliest narratives. Genesis 11:28 refers to “Ur of the Chaldeans” as Abraham’s birthplace, yet the Chaldeans only became a distinct political entity centuries after Abraham’s time. The designation is retrospective—identifying the location by what it later became, not what it was called in Abraham’s era. Biblical scholars recognize this as the author’s way of making ancient geography intelligible to later audiences.

Similarly, Genesis 14:14 mentions “Dan” as a location during Abraham’s lifetime, but Judges 18:29 explicitly states that the city was originally called Laish and only renamed Dan much later. The text projects the later name backward, prioritizing geographical clarity over chronological precision. This is not considered an error but a standard ancient practice.

The pattern extends beyond geography. The biblical authors regularly identify figures and peoples by their eventual historical significance rather than their contemporary designations. The Philistines appear in Genesis narratives set centuries before their historical arrival in Canaan, because the text identifies them by the role they would play in Israel’s later history.

What these examples reveal is that ancient texts encode time differently than modern historical writing. They read history both forward and backward, allowing later meanings to illuminate earlier events. The question is not whether an author “knew” the chronological facts, but whether the naming serves the text’s theological and pedagogical purposes.

The Quran participates in this same literary tradition. By naming the calf’s originator “the Samarian,” it creates deliberate continuity between the wilderness rebellion and the Northern Kingdom’s institutionalized apostasy. The name forces readers to see these not as separate incidents but as a single trajectory of rebellion—exactly what the biblical authors themselves argue through their relentless documentation of calf worship’s persistence.

The Biblical Witness in Continuity

The Quran’s retrospective identification gains historical weight when set against the Bible’s own testimony. Far from presenting calf worship as an isolated lapse corrected by later generations, the biblical narrative insists that the North never repented of this practice. The calf was preserved, defended, and institutionalized—a fact the biblical authors themselves relentlessly document.

To understand this continuity, some historical context is essential. Ancient Israel began as a united kingdom under Saul, David, and Solomon. After Solomon’s death around 930 BCE, the kingdom fractured along regional and tribal lines. The northern tribes broke away under Jeroboam I, forming the Kingdom of Israel (often called the Northern Kingdom), while the southern tribes remained loyal to Solomon’s son Rehoboam, forming the Kingdom of Judah.

This split was not merely political but deeply religious: Jerusalem and its Temple remained in the south, creating a crisis of legitimacy for the north. The northern kings needed to provide their people with an alternative religious center to prevent their subjects from drifting back to Davidic rule. This political necessity set the stage for the religious decision that would define the north’s entire existence.

Jeroboam I faced precisely this dilemma. Jeroboam I faced a political dilemma: if his people continued traveling to Jerusalem for worship, their loyalty might drift back to the Davidic line. His solution was to revive an older religious symbol already embedded in Israelite memory:

“So the king took counsel and made two calves of gold. And he said to the people, ‘You have gone up to Jerusalem long enough. Here are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt.’ He set one in Bethel, and the other he put in Dan.” (1 Kings 12:28–29)

The language is unmistakable. The calves are explicitly tied to the Exodus narrative—the same justification offered in the wilderness episode. This is not innovation but resurrection. The religion of the calf is presented as Israel’s original deliverance theology, now reactivated for political ends.

The biblical writers are equally clear that this act became the defining sin of the Northern Kingdom, repeated formulaically across generations. Jeroboam’s calves were not dismantled by his successors; they became the religious foundation of the state.

The Establishment of Samaria

When Omri rose to power and established Samaria as the capital, no reform occurred:

“Omri did what was evil in the sight of the LORD, and did worse than all who were before him. For he walked in all the ways of Jeroboam the son of Nebat, and in his sin which he made Israel to sin, provoking the LORD God of Israel to anger with their idols.” (1 Kings 16:25–26)

Omri is not accused of inventing a new apostasy. He is condemned for continuity. The calves remain central, and Samaria—newly founded as the capital—becomes the political heart of a kingdom still defined by the same cultic rebellion.

Perpetuation Through Dynasties

This continuity extends through every subsequent dynasty. The biblical historiography relentlessly reiterates the same refrain, as though to prevent readers from imagining any period of repentance:

“He did what was evil in the sight of the LORD, and did not depart from all the sins of Jeroboam the son of Nebat, which he made Israel to sin.” (2 Kings 13:11)

By the time the Northern Kingdom falls to Assyria in 722 BCE, the biblical authors explicitly interpret that catastrophe as the direct consequence of unbroken calf worship stretching back to Jeroboam:

“This occurred because the people of Israel had sinned against the LORD their God, who had brought them up out of the land of Egypt… They worshiped other gods… They walked in the customs of the nations… And in the sins of Jeroboam which he committed, and which he made Israel commit; they did not depart from them.” (2 Kings 17:7, 21–22)

The biblical text collapses centuries into a single moral arc. It does not distinguish between wilderness rebellion, early monarchy, and late monarchy as separate religious eras. Instead, it presents a single, continuous sin—initiated once and perpetuated until judgment fell. Both scriptures agree on the essential point: Israel’s return to the calf was not momentary. It became tradition, institution, and finally judgment.

This political necessity set the stage for the religious decision that would define the north’s entire existence. This northern population and their descendants would later be known as Samaritans—the same group encountered in the New Testament, such as the woman at the well (John 4) and the Good Samaritan (Luke 10). The term derives directly from Samaria, the northern capital that Omri would establish.

Samaria as a Culmination, Not Origin

Samaria was not merely a city founded by Omri in the ninth century BCE. It was the culmination of a religious trajectory that began with the first calf. The Bible itself testifies that the Northern Kingdom never abandoned this symbol, never dismantled its shrines, and never returned to exclusive worship of God.

When Omri bought the hill and established Samaria as his capital, he was not creating something new but consolidating what already existed. The calf cult gave meaning to Samaria, not the reverse. By the time Samaria became the political center, the religious identity was already established. The capital simply institutionalized what Jeroboam had inaugurated.

In this sense, the Quran’s designation is historically precise, not anachronistic. It names the originator by the identity his act ultimately produced. The first calf gives rise to a kingdom of calves, and that kingdom gives rise to Samaria as its capital. The naming follows the axis of meaning, not chronology—exactly as it does with Pharaoh, Qaroon, and Abu Lahab.

The Pattern of Separation and Apostasy

But the connection runs deeper than outcome alone. The Quran’s naming captures not merely what the instigator produced but the very structure of rebellion he initiated. The parallel between wilderness and kingdom is not just thematic but sequential—the same pattern unfolds in both narratives.

In the Quranic account, Moses and the Samarian part ways precisely because of the calf. The separation is both consequence and judgment. Moses confronts the instigator, pronounces his punishment, and the Samarian is expelled from the community: “Then go, and, throughout your life, do not even come close” (20:97). The breach is irreparable. The calf creates division.

Similarly, in the biblical narrative, the North and South part ways, and immediately after this division, the North establishes the calf cult. Jeroboam does not create the calves before the split as a cause of division—he creates them after the split as a consolidation of it. The political separation precedes the religious apostasy, but the apostasy consummates and perpetuates the separation. Once the calves are established, return becomes impossible. The breach is irreparable. The calf creates permanent division.

The sequence is identical: separation followed by the calf, breach followed by apostasy, division consummated by idolatry. In both cases, the calf does not merely represent false worship—it represents the point of no return, the act that makes reunion impossible, the symbol that transforms temporary separation into permanent schism.

By naming the wilderness instigator “the Samarian,” the Quran identifies him not just by what his act would eventually produce geographically but by the pattern of division it would replicate structurally. The name encodes the entire sequence: the one who brought the calf is named after the place where that same pattern—separation consummated by the calf—would define an entire kingdom. The wilderness rebel and the northern kingdom are not merely connected by the symbol they share but by the identical structure of breach and apostasy they embody.

This is why the name is theologically precise. It doesn’t just look forward to Samaria as a place; it identifies the pattern that Samaria would exemplify. The Samarian in the wilderness initiates the sequence; Samaria the capital institutionalizes it. Both involve the same movement: division sealed by the calf, separation made permanent by idolatry.

The Theological Function of the Name

This raises the question: why use this particular designation at all? What theological work does calling him “the Samarian” accomplish that a generic term like “the instigator” or “the deceiver” would not?

The name creates deliberate continuity between wilderness and kingdom, refusing to let readers compartmentalize these as separate incidents—a momentary lapse in the desert versus a later political apostasy. By identifying the originator through the tradition he inaugurated, the Quran insists these are the same rebellion, separated only by time and institutionalization, united by the same pattern of separation and apostasy.

This serves a deeper theological purpose: it reveals the enduring nature of certain forms of disobedience. The calf was not arbitrary improvisation but represented something persistent in human religious imagination—the desire for manageable, visible, controllable divinity combined with the impulse toward division when such control is challenged.

By calling the wilderness instigator “the Samarian,” the Quran identifies him not merely by his act but by its persistence—by the fact that what he initiated would become institutionalized, would survive centuries, would define a kingdom, and would follow the exact same pattern of separation and apostasy. The name is simultaneously retrospective and anticipatory: it looks back from Samaria to identify the origin, and it looks forward from the wilderness to anticipate both the outcome and the pattern that would replicate itself in history.

Why the Calf? Ancient Roots of the Symbol

The deeper continuity matters. The golden calf was not an arbitrary choice in the wilderness. The bull and calf had deep roots in the religious imagination of the ancient Near East. In Egypt, the Apis bull represented vitality, divine presence, and royal power. In Mesopotamian myth, the Bull of Heaven symbolized cosmic authority. For a people recently emerged from Egypt, the calf was familiar, powerful, and reassuringly tangible. It offered a way to conceive of divine presence without the discipline of submission.

This is why the symbol resurfaces. Jeroboam did not invent the calf; he remembered it. The Bible’s own testimony shows him reaching back to exodus tradition to legitimize his new religious system. The calf was already there, dormant in collective memory, waiting to be revived whenever political convenience demanded a more manageable deity—and whenever division needed to be made permanent.

Addressing Possible Objections

The Consistency Objection

One might object that other Quranic figures receive chronologically appropriate names, and that al-Sāmirī represents an inconsistency. If the Quran can name Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh without anachronism, why deploy retrospective naming here?

This objection misunderstands the pattern. The Quran names figures chronologically when chronology is theologically irrelevant—when the person’s identity does not derive from what they inaugurate. Moses is Moses because his personal identity matters; his name carries no moral freight beyond identification. But when a figure’s act defines a tradition, the name reflects that defining role.

Consider: the Quran frequently names individuals and communities not by lineage or ethnicity, but by the concept or idea they represent, where identity is often defined by what one does in relation to revelation, not by ancestry. Names, therefore, operate as archetypes, marking a role in the moral drama rather than a place on a family tree.

This is evident in the Quran’s earliest communal terms. The Muhājirūn (المهاجرون) are defined by migration—the act of leaving behind security for faith. The Anṣār (الأنصار) are defined by support—those who give aid and protection to the believers. The Naṣārā (النصارى) are named for their original act of naṣr (help), preserving the moment when Jesus asked, “Who are my helpers unto God?” In each case, the name does not describe ancestry but an action that becomes an identity. Anyone who performs the act belongs to the category.

The principle is consistent: names encode theological function when function matters. Al-Sāmirī falls into this category precisely because his act inaugurated a tradition that would persist for centuries. The chronological naming of Moses and Aaron does not contradict this; it confirms that the Quran deploys different naming strategies for different theological purposes.

The “Overly Generous” Objection

A more serious objection argues that this reading is overly generous to the Quran, imposing sophistication where simple error exists. Why attribute elaborate theological reasoning to what might be straightforward confusion about when Samaria was founded?

This objection deserves careful engagement. Scholars should indeed be cautious about reading sophistication into texts merely to avoid acknowledging errors. The principle of parsimony suggests we should prefer simpler explanations when they adequately account for the evidence.

However, this objection faces three significant problems:

First, it requires treating the Quran’s established pattern of functional naming—evident in Pharaoh, Qaroon, Abu Lahab, the People of the Elephant, and others—as coincidental rather than methodological. The simpler explanation is that al-Sāmirī follows the same pattern the text employs consistently elsewhere.

Second, it demands we ignore the fact that retrospective naming appears throughout ancient Near Eastern literature, including the Bible itself. The Quran would not be innovating a sophisticated technique but participating in an established literary convention. Attributing this to error requires explaining why the text happens to “err” in precisely the way that ancient texts deliberately employed retrospective designation.

Third, it cannot account for why the Quran would make this particular “error.” If the text simply confused chronology, we might expect random anachronisms scattered throughout. Instead, we find a naming choice that happens to align perfectly with both the biblical testimony about calf worship’s persistence and the text’s own pattern of moral naming. The “error” explanation requires an improbable coincidence: that the Quran accidentally deployed precisely the naming strategy that best captures the theological continuity both scriptures affirm.

The more strained position is not recognizing deliberate method but insisting on coincidental error despite consistent contrary evidence.

The Etymological Alternative

Finally, one might suggest that alternative explanations exist—that al-Sāmirī derives from a non-geographical root, or that the term had meanings now lost to us. Some scholars have proposed connections to Hebrew shamar (to guard, observe), suggesting the name might mean “the keeper” or “the observer.” Others have suggested links to sectarian groups or religious practices unrelated to the city of Samaria.

These possibilities merit consideration and do not contradict the present argument. Language is often multiply determined—words can carry several resonances simultaneously. Whether or not al-Sāmirī possessed additional etymological dimensions, its function within the Quranic narrative remains clear: it identifies the instigator by his legacy, by the tradition his act inaugurated.

Moreover, even if the term originally derived from a non-geographical root, the connection to Samaria—the capital of a kingdom defined by calf worship—would remain theologically significant. The Quran’s audience, familiar with biblical history, would recognize the resonance. The text would be inviting readers to connect wilderness and kingdom, origin and culmination, initial rebellion and institutional apostasy.

In this sense, debating the term’s etymology, while academically valuable, does not resolve the central question: whether the Quran employs anachronistic geography or deliberate theological naming. The pattern of the text, the biblical testimony to continuity, and the theological coherence of the connection all support the latter interpretation.

Reading Scripture on its Own Terms

The charge of anachronism assumes that ancient theological narrative operates according to the conventions of modern historiography—that names must function as strict chronological markers, mechanically tied to dates of founding. This assumption is not neutral; it imposes a recent epistemological framework onto texts that never claimed to operate within it.

The real anachronism is demanding that scripture behave like journalism. Ancient texts encode time, memory, and meaning differently. They name figures according to what those figures represent in the unfolding drama of belief and rebellion. They collapse centuries when those centuries form a single moral arc. They read history not merely forward but also backward, identifying origins by their outcomes.

This is not unique to the Quran. When Genesis calls Abraham’s birthplace “Ur of the Chaldeans,” it does not claim the Chaldeans existed in Abraham’s time. It identifies the location by what readers would recognize, prioritizing clarity over chronological precision. When biblical authors repeatedly collapse Israel’s history into cycles of rebellion and deliverance, they compress time to reveal pattern.

The Quran’s use of al-Sāmirī exemplifies this method. It does not claim that Samaria existed in Moses’ time. It claims that the wilderness calf and the later kingdom of calves are the same rebellion—that Sinai and Samaria are connected not by accident but by continuity. Both the Quran and the Bible testify to this continuity. The biblical authors themselves insist that the Northern Kingdom never repented, that the calf defined the state from Jeroboam to its fall, and that this persistence constituted a single, unbroken sin.

Calling the instigator “the Samarian” is therefore not a historical error but a compressed historical verdict. It tells us that the name came later because the meaning came earlier. The question is not whether the Quran knew when Samaria was founded, but whether we understand how scripture encodes meaning across time.

Conclusion

What we gain by reading the Quran this way is not apologetics but coherence. We recognize a text operating according to its own sophisticated hermeneutical principles—principles that prioritize theological pattern over chronological detail, moral genealogy over geographical precision. What we lose by demanding modern literalism is the capacity to hear what the text is actually saying.

The wilderness calf already belongs to Samaria in moral terms, even before Samaria exists. The Samarian is not an anachronism but a verdict—the judgment that history would eventually confirm. The name encodes both origin and outcome, identifying the first by the last, reading the seed by the harvest it produced.

This reading does not require us to ignore chronology or dismiss historical analysis. It requires us to recognize that ancient texts employed different conventions for encoding time and meaning—conventions that modern readers must learn to recognize rather than dismiss as error. The Quran names the calf’s originator by the tradition he inaugurated because that tradition reveals the deeper continuity both scriptures affirm: that Israel’s rebellion in the wilderness was not momentary but foundational, not corrected but institutionalized, not abandoned but defended until judgment fell.

The charge of anachronism dissolves not because we deny that Samaria was founded centuries after Moses, but because we recognize that the Quran never claimed otherwise. It identifies a wilderness rebel by the kingdom his act would ultimately produce—a naming strategy consistent with both its own established patterns and the broader conventions of ancient Near Eastern literature.

In reading scripture on its own terms, we discover not primitive confusion but sophisticated theology. We find not error but method. And we recognize that the deepest historical insight sometimes requires reading time backward as well as forward, identifying beginnings by their endings, naming origins by their outcomes.

Peace! Would you be willing to chat sometime? I left your discord earlier this year. When I rejoined recently I found out you left, too. I was hoping to connect and see if you’re interested in building bridges with a Quran-alone group in Canada.

LikeLike