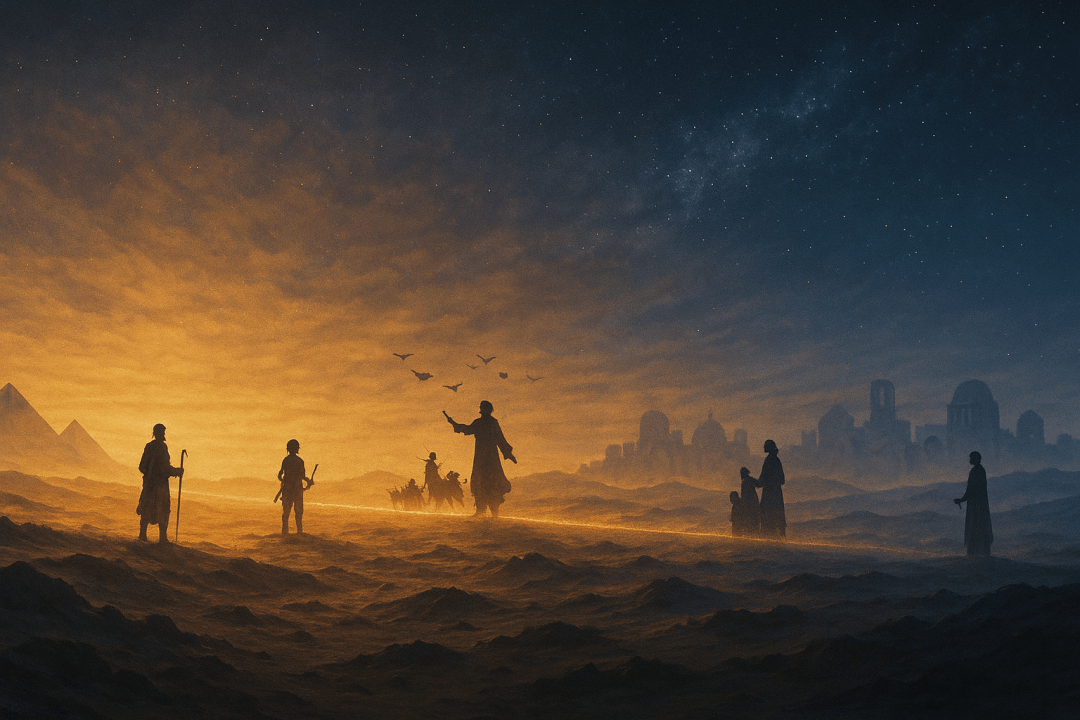

The great irony of the Abrahamic traditions is that their founders began not as kings of vast realms or leaders of tremendous nations, but as figures so marginal that the world around them scarcely took notice. Empires recorded tax quotas, harvest failures, caravan routes, and court intrigues with obsessive regularity; they built monuments to victories both real and imagined. Yet they left almost nothing about the men who would later inspire half of humanity.

The movements of Moses, David, Solomon, Jesus, and Muhammad began not in the halls of power but in tiny communities, in the peripheries of empires, in places so small that even the meticulous scribes of Egypt, Assyria, Rome, and Byzantium could not be bothered to mention them. Their beginnings were humble—so humble, in fact, that only later literature inflated them into the colossal dramas we now read. While the Quran provides an accurate representation of their history, what is found in the Biblical tradition over exaggerates these narratives.

The Quran becomes the interpretive key for understanding the ancient record, as it is the most accurate history (Quran 12:3). These prophets were not commanding vast nations; they were leading handfuls. They were not shaking the world around them; they were barely surviving within it. Their future greatness was invisible to the age that birthed them.

To see the pattern clearly, one must move backward—from Muhammad to Jesus to David and Solomon, finally to Moses—and watch the communities shrink as we move deeper into antiquity, until they become almost invisible. Only then does the historical landscape align with both archaeology and the Quranic insistence that God begins with the few.

Muhammad: The Global Revolution That No Empire Noticed

When Muhammad began preaching in the Hijaz, he lived in a region so marginal that, for the great powers of the age, it might as well not have existed. The Byzantine and Sasanian empires knew of southern Arabia, with its incense routes and Himyarite kings, but Mecca and Medina appear nowhere in their administrative correspondence or military reports. Even the vast corpus of South Arabian inscriptions—thousands of texts spanning centuries—barely acknowledges the existence of the Hijazi towns. As Robert Hoyland notes in Arabia and the Arabs, the Hijaz was a “backwater of backwaters,” a frontier without strategic value and without political relevance.

The towns themselves were small. Pre-Islamic Medina likely housed no more than a few thousand inhabitants clustered by extended families and agricultural oases. Mecca, with its caravans, may have swelled seasonally, but even generous estimates rarely exceed 5,000–10,000 souls. These were not cities that empires feared.

The early Muslim community was even smaller. At Badr, the foundational battle of Islam, the Muslims numbered 313 (Ibn Ishaq; Quran 3:123–125 alludes to divine reinforcement because they were so few), while the Meccan force may have been between 600–1,000. At Uhud they fielded roughly 700. Even at the dramatic conquest of Mecca in 630 CE, the Muslim army of roughly 10,000—the largest force Arabia had seen in generations—was still negligible by imperial standards. For comparison, the Roman army at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312 CE) numbered over 40,000; Khosrow II’s armies regularly deployed 20,000–30,000 men per frontier.

Although the early Muslim community remained small and largely unnoticed by the great empires of the age, the movement’s expansion after Muhammad’s death forced neighboring societies to acknowledge it. Neither Byzantium nor Persia mentions Muhammad by name during his lifetime, a silence that reflects how marginal the Hijaz appeared to them.

But within only a few years of his death, Syriac chroniclers began to take note. The Doctrina Jacobi (c. 634–640) speaks of a prophet arising among the Arabs, though without naming him, and the Syriac Chronicle of 640—often identified with Thomas the Presbyter—mentions Muhammad explicitly in connection with Arab raids in Palestine. These early references, though brief and uncertain, mark a crucial shift: the world began noticing Muhammad’s movement not through his preaching during his life, but through the message that spread after his death—confirming that during his lifetime, he had led a community too small to register on the imperial radar. His significance became visible only after the small desert movement he founded erupted outward with unexpected force.

Jesus: A Teacher Almost Invisible to His Own Age

If Muhammad’s early invisibility is surprising, Jesus’ is astonishing. For the man who would become the most influential figure in Western religious history, the ancient record is almost silent. Roman historians do not mention him while he lived; no provincial governor, tax ledger, or military communiqué records his activity. The Jewish historian Josephus, writing his Antiquities of the Jews around 93–94 CE, spans thousands of names and minute details—cataloging not only the political and religious movements of Judea but even listing various individuals who claimed to be the Messiah.

Within this vast archive, John the Baptist receives a lengthy and unequivocally authentic passage (Ant. 18.5.2), while Jesus receives only two brief references. One of these, the Testimonium Flavianum (Ant. 18.3.3), has long been debated by scholars, with questions about its authenticity and the extent of later Christian interpolation. The other reference, however, Josephus’s mention of Jesus is in the entry for his brother: “James, the brother of Jesus who was called Christ” (Ant. 20.9.1). It is telling: Both John the Baptist and James, not Jesus, appear to be the figures Josephus believed were more worthy of chronicling.

Even the New Testament inadvertently concedes that Jesus’ following was small. The Gospels speak of crowds, but these are literary conventions rather than demographic realities. The same texts that describe thousands gathering for miracles also end with Jesus nearly alone, betrayed, and crucified without significant public reaction. The apocalyptic imagery in Matthew—darkness over the land, earthquakes, and resurrected saints walking the streets (Matt. 27:51–53)—is striking precisely because no contemporary historian records these events. Not Philo of Alexandria, not Seneca, not Pliny, not Josephus.

By contrast, the Quran’s account is far more historically plausible:

O you who believe, be GOD’s supporters, like the disciples of Jesus, son of Mary. When he said to them, “Who are my supporters towards GOD,” they said, “We are GOD’s supporters.” Thus, a group (ṭā’ifah) from the Children of Israel believed, and another group disbelieved. We helped those who believed against their enemy, until they won.

(Quran 61:14)

The Quran never describes mass audiences; it presents Jesus as surrounded by a ṭā’ifah, a small party of loyal followers. And this aligns perfectly with the historical evidence. Jesus’ movement during his lifetime was likely dozens, not thousands. As preserved in the historical record, it appears that during their lives, John the Baptist, by all accounts, made a stronger immediate impression. James, his brother, became the recognized leader of the Jerusalem community—while Jesus remained a relatively obscure figure until later Christian writers reshaped his life into a movement of universal scope.

David and Solomon: Kings Without an Empire

If Jesus leaves barely a trace in the historical record, the figures of David and Solomon fare no better—though the Biblical narrative would have us believe otherwise. According to 2 Samuel and 1 Kings, David forged a vast empire stretching from the Euphrates to the border of Egypt, while Solomon presided over a golden age of monumental architecture, international diplomacy, and immense wealth. Yet archaeology tells a humbler story.

The Tel Dan Stele, a 9th-century BCE Aramaic inscription, is the earliest and clearest non-biblical reference to David, referring to “the House of David.” This confirms David’s historicity but says nothing of an empire. Excavations in Jerusalem show that the city in the 10th century BCE—the supposed age of David and Solomon—contained perhaps 1,000–2,000 inhabitants. It was a small hill-country settlement, not the capital of a Mediterranean empire.

Archaeologists such as Israel Finkelstein have argued, based on pottery sequences and stratigraphic analysis, that monumental architecture attributed to Solomon in earlier scholarship actually dates to a century later (Iron IIA–B), under the Omride dynasty. While Finkelstein’s “low chronology” remains debated among scholars—with some maintaining that a 10th-century date for certain structures remains plausible—even the most generous readings of the archaeological evidence cannot support the imperial scale described in 1 Kings. The gap between the Biblical narrative and the material record remains stark.

As for Solomon, the archaeological record contains no inscription, no building, no seal, no administrative text indisputably linked to him. His wealth, fleets, and international acclaim—described with exuberant detail in 1 Kings 7–10—leave no independent archaeological trace whatsoever.

The Quran, interestingly, places David and Solomon in a spiritual rather than geopolitical register. It speaks of their wisdom, their moral authority, their metaphysical dominion and kingship over creation—not of expansive empires or massive military conquests. When the Quran speaks of their kingship, it refers to their authority and sovereignty over their constituents, not to a vast territorial empire as depicted in the Bible.

Moses and the Exodus: Mathematics Against Myth

If David and Solomon shrink under archaeological scrutiny, Moses nearly disappears. The Biblical narrative declares that “about six hundred thousand men on foot” left Egypt (Exodus 12:37; Numbers 1:46). With women, children, and the elderly included, this implies a total population of two to two and a half million people departing en masse. Yet the historical and archaeological impossibilities begin to mount almost immediately.

To begin with, one must ask: What was the population of Egypt as a whole during the time of Moses? Demographers studying the New Kingdom—roughly the period most commonly associated with any historical Exodus—estimate Egypt’s population at between 2.5 and 4 million, based on agricultural capacity, settlement density, and fragmentary census records. For the Israelites to number in the millions, they would have needed to constitute an ethnic minority nearly equal in size to the Egyptians themselves. This alone strains credibility, but the mathematical implications are even more decisive.

The Bible states that Jacob’s family entered Egypt numbering seventy souls (Genesis 46:27) and that their sojourn lasted 430 years (Exodus 12:40). Although there is longstanding debate over whether this period represents the entire duration of Israel’s residence in Egypt or the broader span from Abraham to the Exodus—as reflected in the differing traditions of the Masoretic Text, the Septuagint, and the Samaritan Pentateuch—the demographic challenge remains the same. To expand from seventy individuals to more than two million within even the longest possible interpretation of that timeline requires an average annual growth rate well above 1.5 to 2 percent, sustained unbroken across four centuries. Such a rate is extraordinary even in the modern world. Preindustrial agrarian societies, hampered by infant mortality, disease, famine cycles, and the limits of subsistence agriculture, typically grew at less than one percent per year—and often far below that. Ancient populations are not known to have achieved, let alone maintained, anything close to the exponential expansion demanded by the Biblical account.

More striking still: this growth would have had to occur despite the oppression described in Exodus itself. According to the narrative, Pharaoh enslaved the Israelites and ordered the systematic killing of male infants (Exodus 1:15–22). For a population to sustain a 2 percent annual growth rate under conditions of enslavement and infanticide is not merely improbable—it approaches demographic impossibility. The Biblical numbers collapse under their own internal contradictions.

A far more realistic demographic scenario—one aligned with Bronze Age mortality patterns—places the Israelite population at the time of the Exodus in the low tens of thousands, not the millions. If the group began with seventy persons and grew for several centuries at rates typical of ancient societies, the resulting numbers fall comfortably within the range of 20,000 to 100,000. These figures not only comport with known population dynamics but also fit within the constraints of Egypt’s total population and the carrying capacity of the Sinai.

Such moderated numbers resonate strikingly with the Quranic portrayal. Pharaoh, sizing up Moses and his followers, dismisses them with aristocratic contempt, refering to them only as a small gang at the time of the exodus.

We inspired Moses: “Travel with My servants; you will be pursued.”

Pharaoh sent to the cities callers.

(Proclaiming,) “This is a small gang.

“They are now opposing us.

“Let us all beware of them.”

(Quran 26:52-56)

This brief line captures, with elegant economy, what archaeology confirms. The Sinai Peninsula contains no trace of the massive encampments, refuse layers, or material culture one would expect from millions of migrants wandering for decades. Egyptian inscriptions—renowned for their bureaucratic precision when documenting foreign workers, military threats, and population movements—record no exodus of such scale. What they do record are smaller Semitic groups: the Habiru, the Shasu, and other itinerant peoples, whose numbers align closely with the demographic range that history allows.

It is worth acknowledging that archaeological absence does not always prove historical absence. Nomadic populations leave minimal traces; wooden structures decay; preservation conditions in certain environments are poor. Yet even accounting for these factors—and granting the most generous interpretations of the evidence—the Biblical claim of millions remains untenable. The Quran’s depiction of a small, oppressed minority quietly slipping out of Egypt is therefore historically coherent, while the Biblical claim of millions reflects a literary inflation—a national epic fashioned to magnify Israel’s origins and dramatize its deliverance.

The Meaning of Small Beginnings

A pattern emerges across the centuries. The further back we go, the smaller the communities become. Muhammad leads a few hundred in the Hijaz; Jesus gathers a circle of disciples; David presides over a hill settlement; Moses confronts Pharaoh with a tiny band. The scribes of later generations magnified these beginnings into grand narratives—an empire for David, millions for Moses, cosmic miracles for Jesus, and tribes swelling into nations overnight. The Quran, by contrast, consistently preserves the older, humbler memory, emphasizing that greatness comes not from numbers but from conviction, resolve, and divine purpose:

…”Many a small army defeated a large army by GOD’s leave. GOD is with those who steadfastly persevere.”

(Quran 2:249)

Consider the perspective of those who lived it. Moses, leading a small band through the Sinai, could not have imagined that billions would invoke his story as a lesson for mankind. The disciples huddled around Jesus in Galilee had no conception that their teacher’s words would reshape empires that had not yet been born. Muhammad’s companions in the early days of Mecca, enduring mockery and persecution, could scarcely have envisioned that their struggle would inspire civilizations from the Atlantic to the Pacific. David, ruling over a modest hill settlement, would have been astonished to learn that his legacy would outlast every empire of his age.

They lived in the immediacy of their moment—hungry, vulnerable, uncertain. They faced doubt from within and hostility from without. The future they hoped for was likely far more modest than the one they inadvertently created. What sustained them was not a grand vision of historical destiny, but something simpler and more essential: conviction in their message, loyalty to one another, and faith that their efforts mattered even if the world seemed indifferent.

This is perhaps the most profound lesson their stories offer. They did not need to see the future to change it. They did not need vast numbers to leave an indelible mark. What they needed—and what they had—was the courage to begin with almost nothing.

Empires trumpet their victories in stone; small communities whisper their hopes around fires. Yet it is the whispers that echo longest. Egypt’s pharaohs carved their deeds into monuments taller than the hills of Jerusalem, but the humble shepherd who challenged them left a far deeper mark on human history. Rome built amphitheaters that still scrape the sky, yet the obscure preacher from Galilee reshaped the moral landscape of continents. Persia ruled from the Nile to the Oxus, but the quiet recitations of a prophet in Mecca outlasted its palaces.

Civilization is repeatedly remade not by the mighty but by the overlooked—those who begin with little more than conviction, a few companions, and a message no one expects to survive. Their humble beginnings are not flaws in the story. They are the story.

[12:3] We narrate to you the most accurate history through the revelation of this Quran. Before this, you were totally unaware.