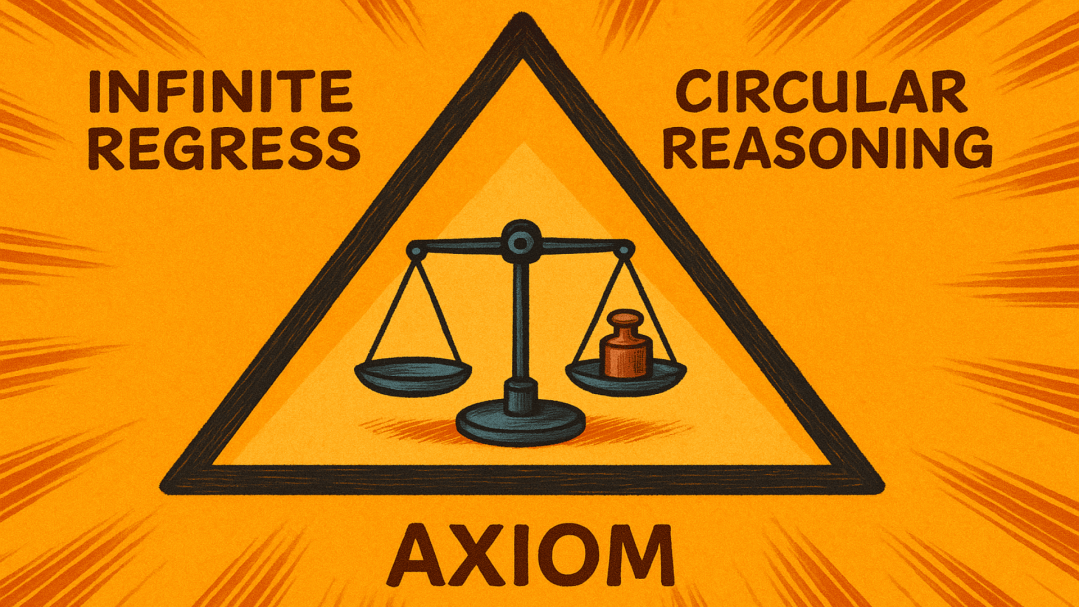

Imagine standing on the edge of reason, asking the most basic question: How do we truly know anything? Every answer you reach for seems to slip through your fingers. If you justify a belief by appealing to another belief, you enter an infinite regress with no foundation. If you loop back on your assumptions to justify themselves, you’ve fallen into circular reasoning. And if you halt the chain of reasoning at some “self-evident” truth, you’re accused of dogmatism.

This unsettling triangle of impossibilities is known as the Münchhausen Trilemma, named after the fabled Baron Münchhausen who claimed he pulled himself out of a swamp by his own hair. It captures the paradox at the heart of human knowledge: no matter how we try to secure certainty, our ladder of reasoning either hangs in the air, spirals forever, or turns back on itself.

The Three Horns of the Dilemma

Philosophers have mapped this challenge as three exhaustive but unsatisfying paths to justification. Each represents a different way our reasoning can fail to provide the solid justification we seek.

Infinite Regress occurs when every proof demands another proof, stretching backward without end. Ask why something is true, and you receive an explanation. Ask why that explanation is true, and you need another explanation, and so on forever. The chain of “why?” questions never terminates in a satisfactory answer.

Circular Reasoning emerges when a belief is supported by another belief that eventually loops back to the first, creating a closed circle rather than a firm foundation. The reasoning becomes self-referential, with each element depending on others in the circle for support.

Foundationalism (sometimes called dogmatism) is where the process stops at a principle that is simply accepted without proof—an axiom we agree to treat as self-evident. While this halts the regress, it does so by declaring certain beliefs beyond question, which feels arbitrary or authoritarian.

The Scale: A Concrete Example

To make this concrete, imagine a conversation about a scale. Someone asks, “How do you know your scale is correct?”

You answer, “Because I tested it against a certified weight.” In which the person further presses, “And how do you know the weight is correct?” “Because I tested it on a laboratory scale,” you respond. The questioner persists: “But how do you know that scale was accurate?” Soon you’re trapped in infinite regress, chasing an endless chain of calibrations.

Alternatively, you might fall into circular reasoning: “The scale is correct because I tested it with this weight, and I know the weight is correct because the scale confirms it.” Here, each element supports the other in a closed loop that provides no external foundation.

Finally, you could embrace foundationalism: “The scale is correct because I calibrate it with this weight, and this weight is the de facto standard.“ The justification halts at an unquestioned axiom, but only by declaring the conversation over rather than providing deeper reasons.

Beyond Philosophy: The Trilemma in Daily Life

What this simple example reveals is that the problem isn’t confined to abstract philosophy—it’s built into the very structure of how we justify things in everyday life. Whether we are testing a scale, defending a belief, or building a scientific theory, our reasoning eventually collides with one of these three options. Either we chase explanations forever, circle back on ourselves, or stop at a foundation we cannot prove but must accept.

Consider science, often held as our most rigorous form of knowledge. Scientific methods are justified by their track record of success, but that track record is evaluated using… scientific methods. Even our most careful empirical investigations rest on foundational assumptions about the reliability of observation, the uniformity of nature, and the validity of logical inference—assumptions we cannot prove without circular reasoning.

Similarly, moral reasoning faces the same challenge. When we claim something is right or wrong, we can trace our justifications back through principles of harm, fairness, or consequence. But eventually we reach bedrock claims about human dignity, the nature of wellbeing, or the structure of reality that we cannot prove from more basic premises.

The Paradox as Guide

Far from being a mere puzzle, the Münchhausen Trilemma exposes the limits of human reason and challenges us to reflect on how we live with those limits. It reminds us that certainty is not the goal of thinking, but rather coherence, usefulness, and ongoing refinement of our understanding.

Every framework of knowledge—scientific, ethical, or practical—represents a choice about how to handle this fundamental challenge. Some embrace the endless inquiry of infinite regress, treating knowledge as an ongoing process rather than a final destination. Others develop coherent circular systems where beliefs support each other in complex webs of mutual justification. Still others ground their thinking in carefully chosen foundational principles, accepting that some starting points must be taken on faith.

The Baron Münchhausen’s impossible feat of self-rescue becomes, in this light, a metaphor not for futility but for the creative audacity required to build knowledge despite its ultimate groundlessness. We cannot pull ourselves up by our own bootstraps, but we can construct remarkably sturdy platforms for understanding and action—knowing all the while that they float on nothing more solid than our collective commitment to making sense of experience.