Abu Hanifa al-Nuʿmān ibn Thābit (699–767 CE / 80–150 AH) was a prominent Islamic scholar and jurist, best known as the founder of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, the oldest and the most widely followed Sunni legal school whose adherents constitute over half of all Sunnis. Born in Kufa, Iraq, he was a merchant by trade but gained recognition for his deep knowledge of Islamic law, theology, and reasoning. He emphasized the use of independent reasoning (ra’y) and analogy (qiyas) in legal judgments, making his school particularly adaptable to diverse contexts.

However, Abu Hanifa was criticized and condemned by proto-Sunni scholars, mainly in the 8-9th centuries, because of his lack of emphasis on Hadith, and it wasn’t until the 10th century onward that scholars attempted to reframe Abu Hanifa as a devout follower of Hadith and as a well respected Sunni.

Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy by Ahmad Khan

Ahmad Khan’s book Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy, Cambridge University Press, 2023, comprehensively analyzes the views of proto-Sunni scholars toward Abu Hanifa between the 8th and 11th centuries. On page 25, it states the three stages of views toward Abu Hanifa.

This chapter reveals the results of a thorough investigation into a large and diverse corpus of texts composed between the ninth and eleventh centuries of discourses of heresy concerning Abū Hanı̄fa. I have identified three distinct stages in the development of hostility towards Abū Hanı̄fa during these centuries. During the first stage (800–850) discourses of heresy towards Abū Hanı̄fa were sharp, but they were limited to specific criticisms. These criticisms tended to be confined to Abū Hanı̄fa’s legal views and his approach to hadı̄th. A more sustained and extensive discourse of heresy emerged only during the second stage (850–950). This period witnessed the emergence of a discourse of heresy designed to establish Abū Hanı̄fa as a heretic and deviant. It was, in my view, the very intensity of this discourse of heresy that occasioned a third shift (900–1000) in discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa. Proto-Sunni traditionalists now began to engender a more accommodating attitude towards Abū Hanı̄fa. This formed the groundwork for the wide embrace of Abū Hanı̄fa among the proto-Sunni community, culminating in his consecration as a saint-scholar and one of the four representatives of Sunni orthodoxy in medieval Islam.

Abu Hanifa Went Against Hadith Rulings

Ibn Abı̄ Shayba (d. 235/849) wrote an entire book entitled, ‘The Refutation of Abū Hanı̄fa’. The book presents 485 reports regarding how Abu Hanifa went against Hadith. For example, the first report is regarding the punishment that is depicted in the Hadith, where the prophet is said to have commanded the stoning of a Jewish couple who committed adultery. Yet, it shows how Abu Hanifa ruled contrary to the Hadith. It states:1

- Sharı̄k b. ʿAbd Allāh < Samāk < Jā bir b. Samura: the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, stoned a Jewish man and a Jewish woman.

- Abū Muʿāwiya and Wakı̄ ʿ < al-Aʿmash < ʿAbd Allāh b. Murra < al-Barā’ b. ʿĀzib: the Messenger of God, God pray over him and grant him peace, stoned a Jewish man.

- Ibn Numayr < ʿUbayd Allāh < Nāfiʿ < Ibn ʿUmar: the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, stoned two Jews, and I was among the people who stoned them both.

- Jarı̄r < Mughı̄ra < al-Shaʿbı̄: the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, stoned a Jewish man and a Jewish woman.

- It is reported that Abū Hanı̄fa said: ‘They are not to be stoned.’

The final report discusses the ruling on charity giving and again shows how Abu Hanifa went against the ruling found in the Hadith.2

- Abū Khālidal-Ahmar < Yahyā b.Saʿı̄d < ʿAmrb.Yahyā b.ʿUmāra < his father < Abı̄ Saʿı̄d said: the Messenger of God, God pray over him and grant him peace, said: ‘No charity (sadaqa) is due on anything less than five aswāq.’

- Abū Usāma < Walı̄d b. Kathı̄r < Muhammad b. ʿAbd al-Rahmāṅ b. Abı̄ Saʿ ̇saʿa < Yah ̇ yāb. ʿUmāra and ʿIbād b. Tamı̄m < Abı̄ Saʿı̄d al-Khudrı̄ : he heard the Messenger of God, God pray over him and grant him peace, say: ‘There is no charity due on anything less than five aswāq of dates.’

- ʿAlı̄ b. Ishāq < Ibn Mubārak < Maʿmar < Suhayl < his father < Abū Hurayra: The Prophet of God, God pray over him and give him peace, said: ‘There is no charity due on anything less than five aswāq.’

- It is reported that Abū Hanı̄fa said: ‘Charity is due on anything that exceeds or is less than this.’

All Reputable Sunni Scholars Condmened Abu Hanifa

ʿAbd Allāh b. ʿAdı̄ b. ʿAbd Allāh b. Muhammad b. Mubārak, better known to modern scholars as Ibn ʿAdı̄, was born in Jurjā n in 277/890. He describes Abū Hanı̄fa as:

[A] devil who opposed the reports of the Prophet Muhammad with his speculative jurisprudence.3

In his book al-Kāmil he has the following statement to say about Abu Hanifa:

There is a consensus of the scholars as to the fall of Abū Hanı̄fa. We know this because the leading authority of Basra, Ayyūb al-Sakhtiyānı̄ had aspersed him; the leading authority of Kufa, al-Thawrı̄ , had aspersed him; the leading authority of the Hijāz, Mālik, had aspersed him; the leading authority of Misr, al-Layth b. Saʿd, had aspersed him; the leading authority of Shām, al-Awzāı̄ , had aspersed him; and the leading authority of Khurāsān, ʿAbd Allāh ̇ b. al-Mubārak, had aspersed him. That is to say, we have here the consensus of the scholars in all of the regions.4

In another place, Ibn ʿAdı̄ expresses the very same sentiment:

‘There is not a scholar who is well respected except that he has denounced Abū Hanı̄fa.’5

Imam Malik: Abu Hanifa Was An Incurable Disease

Elsewhere, he refers to a report narrated by Ibn Hanbal, Ibn Abu Dawud, and Malik ibn Anas, calling Abu Hanifa an incurable disease.

ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal > Mutrif al-Yasārı̄ al-Asamm > Mālik b. Anas said: ‘The incurable disease is the destruction of faith. Abū Hanı̄fa is the incurable disease.’6

Ibn ʿAdı ̄ > Ibn Abı ̄ Dawud > al-Rabıʿ b. Sulayman al-Jızı > al-Harith b. Miskın > Ibn al-Qāsim > Mālik said: ‘The incurable disease is the destruction of faith, and Abū Hanı̄fa is [one manifestation] of the incurable disease.’7

No One More Harmful to Islam Than Abu Hanifa

Additionally, Ibn ʿAdı̄ recalls how proto-Sunnis like Sufyān al-Thawrı̄ celebrated when he learned of Abū Hanı̄fa’s passing:

‘Praise be to God. He was destroying Islam systematically. No one was born in Islam more harmful than him.’8

Bukhari: No One More Harmful to Islam Than Abu Hanifa

We see similar sentiments to the death of Abu Hanifa from other prominent Sunni scholars. Most notably, Bukhari (d. 256/870) has the following report stated in his al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat.

Nuʿaym b. Hammād < al-Fazārı̄ said: ‘I was with Sufyān when news of al-Nuʿmān‘s [Abu Hanifa’s] death arrived. He said: “Praise be to God. He was destroying Islam systematically. No one has been born in Islam more harmful than he [was].”9

Mālik b. Anas, founder of the Maliki school, had the same sentiment as he reported:

‘No one was born in Islam whose birth was more harmful to the Muslims than that of Abū Hanı̄fa.’10

In another book by Bukhari, Kitāb al-Duʿafā ’ al-saghı̄r, Khan has the following to say regarding his entry on Abu Hanifa:

However, al-Bukhārı̄ appears to give Abū Hanı̄fa special treatment. His entry on Abū Hanı̄fa relates three damning reports attacking Abū Hanı̄fa’s religious credibility. The first report maintains that Abū Hanı̄fa repented from heresy twice. The second report states that when Sufyān al-Thawrı̄ heard that Abū Hanı̄fa had passed away, he praised God, performed a prostration (of gratitude), and declared that Abū Hanı̄fa was committed to destroying Islam systematically and that nobody in Islam had been born more harmful than he. The third and final report, which al-Bukhārı̄ also includes in his al-Tārı̄kh al-kabı̄r, describes Abū Hanı̄fa as one of the anti-Christs.11

Ibn Qutayba: We Loath Abu Hanifa Because His Rulings Oppose Hadith

Ibn Qutayba (d. 276/889) explains that they loathed Abu Hanifa because he rejected the rulings found in Hadith.

We do not loathe (lā nanqimu) Abū Hanı̄fa because he employs speculative jurisprudence, for all of us to do this (kullunā yarā). However, we loathe him because when a hadı̄th comes to him on the authority of the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, he opposes it (yukhālifuhu) in preference for something else.12

Bukhari: Abu Hanifa Did Not Do Salawat Upon the Prophet

In another report from Bukhari, he states that Abu Hanifa and his students did not do salawat upon the prophet.

Whenever I wanted to see Sufyān, I saw him praying [upon the Prophet] or narrating hadı̄th, or engaged in abstruse matters of law (fı̄ ghā mi ̇d al-fiqh). As for the other gathering that I witnessed, no one prayed upon the Prophet in it.13

Bukhari explains at the end of this report, ‘he means [the gathering of] al-Nuʿmān’ (Abu Hanifa).

This is also confirmed by a report from Abdullah Ibn Ahmad Ibn Hanbal in his Kitāb al-Sunna.

On lookers observed that when Abū Hanı̄fa was presiding over lessons in the mosque there would be laughter and people would be raising their voices. Others were affronted by more serious charges, namely, that Abū Hanı̄fa’s lessons would go on without their being any praise for the Prophet Muhammad.14

Ibn Hanbal Condemned Abu Hanifa

One of Abu Hanifa’s most ardent opponents was Ibn Hanbal (d. 241/855), founder of the Hanbali Madhab. Ibn Hanbal’s son carried on his legacy and continued to rally against Abu Hanifa.

ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal rallied against Abū Hanı̄fa for supposedly permitting the consumption of pork, alcohol, and other prohibited drinks.84 He was aghast at Abū Hanı̄fa’s edict that breaking musical instruments was a punishable crime.85 Other proto-Sunni traditionalists claimed that Abū Hanı̄fa permitted adultery and usury and that his jurisprudence led to the shedding of blood with impunity.86 Many were, of course, puzzled and startled by these allegations. When a sceptic demanded an explanation, he was told that Abū Hanı̄fa permitted usury because he did not object to deferred credit transactions that accrue additional charges (nası̄’a); he permitted public violence (al-dimā’) since he ruled that if a man kills another man by striking him with a massive stone, the blood money must be paid by his male relatives, tribe, or social group (al-ʿāqila); he permitted adultery because he ruled that if a man and a woman have sexual intercourse in a house, whilst they are known to be parents, and both declare themselves that they are married to each other, no one should object to them. Upon hearing this detailed explanation the sceptic remarked that all of this amounted to invalidating God’s laws (al-sharā’iʿ) and injunctions (al-ahkām).87

Kitāb al-Sunna’s Condemnation of Abu Hanifa

Ibn Hanbal’s son Abd Allah (d. 290/903), who carried on his legacy, wrote a thorough refutation showing how Abu Hanifa was outside of the fold of Sunni Islam. We see the following excerpt regarding this topic:

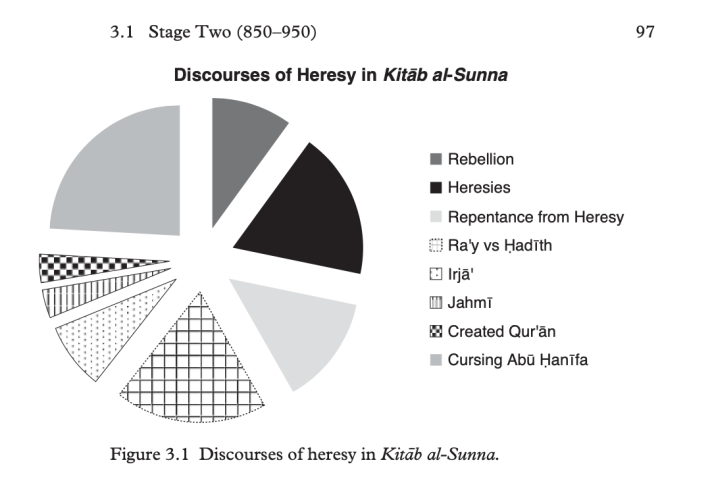

But we can measure the importance of discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa to proto-Sunni traditionalists by the fact that ʿAbd Allāh’s Kitāb al-Sunna devotes almost fifty pages to portraying Abū Hanı̄fa as a heresiarch.253 ʿAbd Allāh’s method for depicting Abū Hanı̄fa as a heretic and deviant observes the norms of religious authority current among proto-Sunni traditionalists of the ninth century. Rather than communicating his own thoughts and ideas about Abū Hanı̄fa, ʿAbd Allāh proposes to relate information he heard from a select group of religious authorities…

The Kitāb al-Sunna evidences a number of themes that form the basis of discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa (see Figure 3.1). I have counted a total number of 184 anti-Abū Hanı̄fa reports in this section of the Kitāb al-Sunna. There are six overarching (and overlapping) themes in the material ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal collects against Abū Hanı̄fa. Most of the (forty-one) reports fall into the category of general curses against Abū Hanı̄fa. Within this category we have reports describing Abū Hanı̄fa as the greatest source of harm to Islam and Muslims; the most wretched person to be born in the religion of Islam; prayers and curses against Abū Hanı̄fa; and expressions of joy at the news of his death. The second prominent theme is the opposition between Abū Hanı̄fa’s ra’y and Prophetic hadı̄th (thirty-two reports). This is followed closely by the theme of heresies (thirty-one reports). This category refers to reports wherein the semantic field of heresy (kufr, kāfir; zandaqa, zindı̄q; murūq, mā riq, etc.) is employed against Abū Hanı̄fa. Examples of reports from this category include a report in which a proto-Sunni traditionalist encouraged his colleague to declare Abū Hanı̄fa an unbeliever (kāfir)

and heretic (zindı̄q) because he believed the Quran to be created;255 students of Mālik b. Anas alleged that he declared Abū Hanı̄fa to be beyond the pale of the religion;256 on a separate occasion, when someone proposed one of Abū Hanı̄fa’s solutions to a legal question, it was dismissed curtly as the view of ‘that apostate’.257 The fourth theme refers to reports that describe Abū Hanı̄fa as having repented publicly from heresy (twenty-three reports). Another prominent theme is rebellion (seventeen reports). ʿAbd Allāh collects reports in which proto-Sunni traditionalists drew attention to the heretical nature of Abū Hanı̄fa’s support for rebellion against Muslim rulers. A sixth theme is Abū Hanı̄fa’s adherence to the heresy of Irjā’ (fourteen reports). Little is made of Abū Hanı̄fa’s views on the Quran (six reports) and his connection to the Jahmiyya (six reports), which is especially surprising given the historical background of the Mihna and the involvement of the author’s father, Ahmad b. Hanbal, in that inquisition. There is no doubt that the Kitāb al-Sunna represented the culmination of proto-Sunni traditionalist attempts to place Abū Hanı̄fa outside the realm of orthodoxy and that the close students of Ahmad b. Hanbal were at the forefront of disseminating discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa.15

Below are some of the reports on Abu Hanifa found in the Kittab al-Sunnah published in 2022 and translated by Abū Hājar.

228. And it was narrated to me from Ishāq ibn Mansūr Al-Kawsaj who said: I said to Ahmad ibn Hanbal: “Is a man rewarded for hating Abū Hanīfah and his companions?” He said: “Yes, by Allāh.”

229. I asked my father – rahimahullāh – about a man who wants to ask about something from the matters of his religion – regarding what he is tested in of oath in divorce and other things – in the presence of the people from the people of raī (opinion) and from the people of hadīth who did not memorize nor do they know the hadīth with a weak isnād and with a strong isnād, then who should he ask, the people of raī or the people of hadīth despite of the lack of knowledge that they have? He said: “He should ask the people of hadīth and should not ask the people of raī. The weak hadīth is better than the opinion of Abū Hanīfah.”

230. Muhannah ibn Yahyā Ash-Shāmī narrated to me (and said): I heard Ahmad ibn Hanbal say: “For me the opinion of Abū Hanīfah and dung, are the same.”

236. Ishāq ibn ‘Abdir-Rahmān narrated to me, from Hasan ibn Abī Mālik, from Abū Yūsuf who said: “The first one to say that the Qurān is created was Abū Hanīfah.”

241. Ishāq ibn Abī Ya’qūb At-Tūsī narrated to me (and said): Ahmad ibn ‘Abdillāh ibn Yūnus narrated to us, from Salm Al-Muqrī, from Sufyān Ath-Thawrī who said: I heard Hammād say: “Are you not astonished that Abū Hanīfah says: The Qurān is created? Say to him: ‘You kāfir, you zindīq.’”

247. Abū Al-Fad Al- Khurasānī narrated to me and said: Surayj ibn An-Nu’mān narrated to us, from Hajjāj ibn Muhammad who said: “It has reached me from Al- Awzā’ī that Abū Hanīfah threw away the usūl and turned to qiyās.”

249. Abū Bakr ibn Zanjuway narrated to me (and said): Abū Ja’far Al-Harrānī narrated to us and said: I heard ‘Īsā ibn Yūnus say: Al ‘Awzā’ī went out to me, Al- Mu’āfā ibn ‘Imrān and Mūsā ibn A’yan, while we were with him in Bayruwāh, with the book Kitāb As-Siyar, and what given as answers to Abū Hanīfah. Then he said: “If this mistake had been divided over the Ummah of Muhammad, it would verily have encompassed all of them. No newborn was born in Islām that was worse for them (i.e. the Muslims) than Abū Hanīfah.”

251 – Muhammad ibn Hārūn Abī Nashīt narrated to me and said: Abū Sālih Al- Farrā narrated to us (and said): I heard Al-Fazārī (i.e. Abū Ishāq) say: Al-Awzā’ī said to me: “That which we resent Abū Hanīfah for, is that he would come to the hadīth of the Prophet, and then he would contradict it to something else.”

252. Muhammad ibn Hārūn narrated to me and said: Abū Sālih narrated to us and said: I heard Al-Fazārī and Sufyān both say: “Nobody was born in Islām that is more calamitous for this Ummah, than Abū Hanīfah.”

274. My father narrated to me (and said): Muammal ibn Ismā’īl narrated to us, from Sufyān who said: ‘Abbād ibn Kathīr narrated to me and said: ’Umar ibn… said to me: “Ask Abū Hanīfah about a man who says: ‘I know that the Ka’bah is true and that it is the House of Allāh – ‘azza wa jalla – but I do not know if it is the Ka’bah which is in Makkah or the one in Khurasān’, is he a believer?” He said: “He is a believer.” So he said to me: “Ask him about a man who says: ‘I know that Muhammad is true and that he is a messenger, but I do not know if he is the one who was in Madīnah or another Muhammad’, is he a believer?’ He said: “He is a believer.”

275. Hārūn ibn ‘Abdillāh narrated to me, from ‘Abdullāh ibn Az-Zubayr Al- Humaydī, from Hamzah ibn Al-Hārith ibn ‘Umair – from the family of ‘Umar ibn Al-Khattāb (radiAllāhu ‘anhu) – from his father who said: I heard a man ask Abū Hanīfah about Al-Masjid Al-Harām regarding a man who said: “I testify that Al- Ka’bah is true but I don’t know if it is this one or not?” So he said: “He is a true believer.” And he asked him about a man who said: “I testify that Muhammad ibn ‘Abdillāh is a prophet, but I don’t know if he is the one whose grave is in Madīnah or not.” So he said: “He is a true believer.” Al-Humaydī said: “Whoever says this has verily committed kufr.” Al-Humaydī said: “And Sufyān ibn ‘Uyaynah used to narrate from Hamzah ibn Al-Hārith.”

295. Abū Al-Fadl Al-Khurasānī narrated to me and said: Ismā’īl ibn Abī Uways narrated to us and said: My uncle Mālik ibn Anas said to me: “Abū Hanīfah is from the chronic diseases.” And Mālik said: “Abū Hanīfah invalidates the Sunan (pl. Sunnah).”

306. Muhammad ibn ‘Amr Al-Bāhilī narrated to me (and said): Al-Asma’ī narrated to us, from Sharīk who said: “The companions of Abū Hanīfah are worse for the Muslims than the same number of them of merchant thieves from Qumm (a city in Īrān).”

308. Abū Al-Fadl Al-Khurasānī narrated to me (and said): Abū Nu’aym narrated to us and said: Sharīk would have a very bad opinion about Abū Hanīfah and his companions, and he would say: “Their madhhab is to refute the narrations from the Messenger of Allāh.”

316. Ibrāhīm narrated to me (and said): I heard ‘Umar ibn Hafs ibn Ghiyāth narrate from his father who said: “I used to sit with Abū Hanīfah and hear him give fatwā in one issue with five different opinions in one day. So when I saw that, I left him and turned to the hadīth.”

322. Ibrāhīm narrated to me and said: Abū Tawbah narrated to us, from Abū Ishāq Al-Fazārī who said: I narrated a hadīth from the Messenger of Allāh to Abū Hanīfah regarding keeping the sword (from the Muslims), so he said: “That hadīth is superstition.”

326. Ibrāhīm narrated to me and said: Abū Tawbah narrated to us, from Abū Ishāq Al-Fazārī who said: Al-Awzā’ī said: “Verily we do not have anything against the opinion of Abū Hanīfah, because we all have an opinion. But we verily have against him that if a hadīth from the Messenger is mentioned to him, and then he gives a fatwā of the opposite of it.”

334. Abū Ma’mar narrated to me, from Yahyā ibn Yamān who said: I heard Sharīk say: “Expel whoever is here from the companions of Abū Hanīfah and remember their faces.”

340. My father – rahimahullāh – narrated to me (and said): Muammal ibn Ismā’īl narrated to us and said: I heard Hammād ibn Salamah when he mentioned Abū Hanīfah, then he said: “Verily Abū Hanīfah met the narrations and the Sunan with his refutation of them using his opinion.”

343. Ahmad ibn Ibrāhīm Ad-Dawraqī narrated to me, from Al-Haytham ibn Jamīl who said: I heard Hammād ibn Salamah say regarding Abū Hanīfah: “Allāh will verily throw that one in Hellfire.”

345. Muhammad ibn Abī ‘Attāb Al-A’yan narrated to me, from Mansūr ibn Salamah Al-Khuzā’ī who said: “I heard Hammād ibn Salamah curse Abū Hanīfah.” Abū Salamah said: “And Shu’bah (ibn Al-Hajjāj) used to curse Abū Hanīfah.”

350. Al-Qāsim ibn Muhammad Al-Khurasānī narrated to me and said: ‘Abdān narrated to us, from Ibn Al-Mubārak who said: “On the face of the earth there is not a gathering which is more beloved to me, than the gathering of Sufyān Ath-Thawrī. You used to, if you wanted to see him pray, you would (be able to) see him pray, and if you wanted to see him remembering Allāh, then you would (be able to) see him (do that), and if you wanted to see him dealing with the difficult of fiqh, then you would (be able to) see him (do that). But a gathering, in which I don’t know if I ever witnessed him sending blessings upon the Prophet , then it’s the gathering.” And he became quiet and didn’t mention (any name). So he (‘Abdān) said: That is the gathering of Abū Hanīfah.

369. Muhammad ibn Hārūn narrated to me (and said): Abū Sālih narrated to us and said: I heard Al-Fazārī say: “I narrated the hadīth of the Prophet to Abū Hanīfah about withholding the sword (from the Muslims), so he said: ‘That hadīth is superstition.’”

383. Abū Al-Fadl narrated to me (and said): Muhammad ibn Mihrān Al-Jamāl Ar- Rāzī narrated to us, from someone who narrated to him from Ibn Al-Mubārak that he was asked about an issue, so he narrated some ahādīth about it. Then the man said to him: “Verily Abū Hanīfah says the opposite of this.” So Ibn Al-Mubārak became angry and said: “I have informed you from the Prophet and his companions, and you bring me a man who considers the sword (permissible) against the Ummah of Muhammad ”.

387. I was informed from Mutarrif Al-Yasārī Al-Asam, from Mālik ibn Anas who said: “The chronic disease in the religion is destruction. Abū Hanīfah is the chronic disease.”

391. Abū Al-Fadl narrated to me (and said): Mas’ūd ibn Khalaf narrated to me (and said): Ishāq ibn ‘Īsā narrated to me (and said): Muhammad ibn Jābir narrated to me and said: I heard Abū Hanīfah say: “’Umar ibn Al-Khattāb made a mistake.” So I took a handful of pebbles and threw them in his face.

392. Abū Al-Fadl Al-Khurasānī narrated to me (and said): Hammād ibn Abī Hamzah As-Sukkarī narrated to us, from Salamah ibn Sulaymān, from Ibn Al-Mubārak, that a man asked him regarding an issue. So he narrated a hadīth to him regarding it from the Prophet. So the man said: “Abū Hanīfah says the opposite of this.” So Ibn Al-Mubārak became very angry and said: “I narrated to you from the Messenger of Allāh and you come to me with the opinion of a man who opposes the hadīth? I will not narrate any hadīth to you today.” And he got up (and left).

397. Muhammad ibn Hārūn narrated to me (and said): Abū Salih narrated to us and said: I heard Yūsuf ibn Asbāt say: “Abū Hanīfah was not born upon the fitrah.” And I heard Yūsuf say: “Abū Hanīfah opposed (with his opinion) four hundred narrations from the Prophet.”

400. Abū Al-Fadl Al-Khurasānī narrated to me (and said): Muhammad ibn Ja’far Al-Madāinī narrated to us and said: Muhammad ibn Jābir said: I heard Abū Hanīfah when a man narrated a hadīth to him from ‘Umar ibn Al-Khattāb (radiAllāhu ‘anhu), so he said: “’Umar ibn Al-Khattāb was mistaken.” So I took a handful of pebbles and threw them at him.

401. Abū Al-Fadl narrated to me (and said): Yahyā ibn Ayyūb narrated to us (and said): ‘Alī ibn ‘Āsim narrated to us and said: I narrated a hadīth to Abū Hanīfah regarding marriage or divorce. He said: “That is the judgment of the Shaytān.”

403. Abū Al-Fadl narrated to me (and said): Muslim ibn Ibrāhīm narrated to us (and said): ‘Abdul-Wārith ibn Sa’īd narrated to us and said: from Sa’īd narrated to us and said: I was sitting with Abū Hanīfah in Makkah when he mentioned something. So a man said to him: “’Umar ibn Al-Khattāb has narrated this and this.” Abū Hanīfah said: “That is the opinion of the Shaytān.” And another man said to him: “Has it not been narrated from the Messenger of Allāh: “The cupper and the one whom cupping is done both break their fast.’” So he said: “This is a rhyme.” So I got angry and said: “I will verily never return to this gathering.” And I walked away and left him.

405. Abū Al-Fadl Al-Khurasānī narrated to me (and said): Abū Al-Ahwas Muhammad ibn Hayyān narrated to us and said: One day a man asked Hushaym about an issue, so he narrated a hadīth to him regarding it. So the man said: “Verily Abū Hanīfah, Muhammad ibn Al-Hasan and his companions say the opposite of this.” So Hushaym said: “O slave of Allāh. Verily, knowledge is not taken from the bottom.”

410. Abū Ma’mar narrated to us, from Ishāq ibn At-Tabbā’ who said: Muhammad ibn Jābir said: I heard Abū Hanīfah – in the masjid of Kūfah – say: “’Umar ibn Al- Khattāb was mistaken.” So I took a handful of pebbles and threw them at his face and chest.

Even when Abu Hanifa’s followers attempted to claim that Abu Hanifa disseminated Hadith, no Sunni muhaddath considered Abu Hanifa reliable in what was attributed to him. Abū Bakr al-Marrūdhı̄ (d. 275/888), in his Kitāb al-Waraʿ, presents the following statement against someone who mentioned a Hadith that he attributed to Abu Hanifa.

Abd al-Rahmān b. Mahdı̄: Forget them. How dare you mention ʿAbd Allāh’s transmission from Abū Hanı̄fa in the course of an elegy! Do you not know that for ʿAbd Allāh there is nothing more debased than the dirt of Iraq than his transmitting from Abū Hanı̄fa? How I wish he had not transmitted from him (law wadadtu annahu lam yarwi ʿanhu)! How I would have ransomed a great portion of my wealth to have ensured that (wa innı̄ kuntu aftadı̄ dhālika bi ʿa ̇zm mālı̄)!16

Khan states the following regarding the early muhaddith’s views on transmitting from Abu Hanifa.

Al-Tirmidhı̄ (d. 279/892) claimed that Abū Hanı̄fa had told his students as much: ‘Most of the hadı̄th I relate to you are mistaken (ʿāmmatu mā uhaddithukum khata’).’17

Muslim b. al-Hajjāj’s book on the subject of hadı̄th transmitters and their nicknames arrived at a similar conclusion: Abū Hanı̄fa was deficient in hadı̄th, and had very few sound hadı̄th.18 Al-Nasā’ı̄’s verdict was that Abū Hanı̄fa ̇ was weak in hadı̄th.19 In his short book describing the standards of individual hadı̄th scholars, al-Jūzajānı̄ described Abū Hanı̄fa as someone whose hadı̄th could not be relied upon.20 In his Sunan, al- Dāraqut’nı̄ called Abū Hanı̄fa weak (daʿı̄f) in hadı̄th, and reportedly communicated the same point to Hamza al-Sahmı̄. Still, Abū Hanı̄fa found no place in al-Dāraqutnı̄’s history of weak hadı̄th scholars.21 He also added that Abū Hanı̄fa’s hadı̄th transmissions were unreliable since he never met a Companion.

al-Bajalı̄, al-ʿUqaylı̄ quotes the expertise of ʿAbd Allā h b. Ahmad b. Hanbal. When the latter was asked whether al-Bajalı̄ was a reliable hadı̄th scholar (sadūq), he replied: ‘No one should relate anything on the authority of Abū Hanı̄fa’s followers (ashāb Abı̄ Hanı̄fa).’ ̇ ̇ ̇ 22

Al-Jawraqānı̄’s (d. 543/1148) book on false and sound hadı̄ths twice cites hadı̄ths containing Abū Hanı̄fa in the isnāds. He declares them to be false and states that Abū Hanı̄fa’s hadı̄ths are to be renounced (matrūk al-hadı̄th).23

10th-century scholar Ibn Hibbān (d. 354/965) makes the following determination of Abu Hanifa according to p. 323-324 of the book.

Ibn Hibbān tells us that Abū Hanıfa transmitted 130 hadıths with isnads. Ibn Hibban wrote with supreme confidence that there are no other hadı̄ths from him in the entire world other than these 130. Of these 130 hadı̄ths, Ibn Hibbān believed that Abū Hanı̄fa had committed errors in 120 by way of either mixing up the isnāds or changing the matn. He concludes that in situations when someone’s errors significantly outweigh their positive results, their traditions cannot be relied upon. This seems like a précis of Ibn Hibbān’s now lost book on the defects of Abū Hanı̄fa’s hadı̄ths. For Ibn Hibbān this was not the only reason for Abū Hanı̄fa to be denounced. He continues in the next sentence: ‘There is another reason why one cannot use him as a proof and that is because he invited people to [the heresy of] Irjā’, and there is a total consensus among every single one of our imams that one may not rely upon somebody as a proof if he calls others to heresy (al-bidaʿ).’24

Additionally, Ibn Hibban states:

Among every single one of our imams, I know of no disagreement between them concerning him [Abū Hanı̄fa]: the leaders of the Muslims and those of scrupulous piety in the religion, in all of the regions and provinces [of the Islamic world], one after another, they all have declared him to be unreliable and have vilified him. We have included examples of these statements in our book entitled ‘The Warning about the Falsification’. There is no need, then, to repeat all of this in our present book. Instead, I shall simply cite here a summary from which readers will be able to deduce for themselves everything else that lies behind it.25

Final Thoughts

The historical reception of Abu Hanifa reveals that proto-Sunnis unanimously condemned Abu Hanifa because he did not utilize Hadith in his legal reasoning and often went against the rulings of established Hadith. Figures such as Malik ibn Anas, Ahmad ibn Hanbal, and even Bukhari openly denounced him, viewing his jurisprudential methods as a threat to Islamic tradition and even celebrating his death. Early Hadith scholars consistently rejected his reliability in transmitting Hadith when his students attempted to formulate Hadith on his behalf in an attempt to save his reputation. Yet, despite their relentless efforts to discredit him, history took an unexpected turn—one that would force Sunni orthodoxy into an ideological retreat.

The reality is that all the cursing and condemnation did nothing to slow the rise of the Hanafi school. Under the patronage of powerful Islamic empires like the Abbasids and Seljuks, the Hanafi madhab rapidly became the dominant school of jurisprudence across vast regions, including the Indian subcontinent, Turkey, Central Asia, and the Levant. Its emphasis on ra’y (independent reasoning) and qiyas (analogical reasoning) made it highly adaptable, ensuring its widespread acceptance among Muslim communities. The sheer number of Hanafi adherents became impossible to ignore, and Sunni orthodoxy found itself in a dilemma: how could they maintain their traditional condemnation of Abu Hanifa when his legal school had already become the de facto foundation of Islamic law for millions?

Rather than continue waging an unwinnable war against Abu Hanifa’s legacy, later Sunni scholars devised a strategic solution—they rebranded him as Sunni. Instead of portraying him as the dangerous innovator their predecessors had warned against, they transformed him into a pillar of Sunni orthodoxy. Fabricated musnads were attributed to him, falsely presenting him as a devoted transmitter of Hadith. His legal methodology, which had once been condemned as reckless speculation, was repackaged as fully in line with Sunni principles. This historical revisionism allowed Sunni orthodoxy to absorb the Hanafi school without having to confront the glaring contradiction between their newfound praise and their past hostility.

By making Abu Hanifa “Sunni,” they made his followers Sunni by default. Rather than alienating the vast Hanafi majority or trying to dismantle the legal system they relied on, they simply rewrote history to make it appear as though Abu Hanifa had always been a champion of Hadith and Sunnah. The result was one of the most successful ideological takeovers in Islamic history—millions of Hanafis, to this day, believe their tradition was always deeply rooted in Sunni orthodoxy, unaware that their founder was once considered the very definition of a heretic.

Related Articles:

https://hadithcriticblog.com/imam-abu-hanifa-false-attributions/

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 35-36, & Ibn Abı̄ Shayba, al-Musannaf, ed. Muhammad ʿAwwā ma (Jeddah: Dār al-Qibla li al-Thaqā fa al-Islā miyya, 2006), 20: 53–4 = (Hyderabad: al-Ma ̇tbaʿa al-ʿAzı̄ ziyya, 1966), 14: 148–9. ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 35-36, & Ibn Abı̄ Shayba, al-Musannaf, 20: 216–17 = 14: 281–2.

↩︎ - Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 334 & Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 239 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 125).

↩︎ - Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 334 & Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 241 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 129) ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 334 & Ibn ʿAdı̄ , al-Kā mil, 8: 238 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 123) ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 250 & ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal, Kitāb al-Sunna, 223. ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 250 & Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil fı̄ al- ̇duʿafā’ al-rijāl, 8: 236–7 (ʿAbd al-Mawjū d edn.). ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 334 & Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 239 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 126). ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 65 & Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat, 4:503 (Abū Haymadedn) = 2:77 (al-Luhaydānedn) ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 242 & Al-Fasawı̄, Kitāb al-Maʿrifa wa al-tārı̄kh, 2: 790. ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 67-68, Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Duʿafā’ al-saghı̄r, ed. Abū ʿAbd Allā h Ahmad b. Ibrāhı̄m b. Abı̄ al-ʿAynayn (n.p.: Maktabat Ibn ʿAbbā s, 2005), 132 ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 74 & Ibn Qutayba, Ta’wı̄l mukhtalif al-hadı̄th, 63 (Zakı̄ al-Kurdı̄edn.) & Abd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal, Kitāb al-Sunna, 210 ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p.66, & Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat, 2:113–14 (al-Luhaydānedn) ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 242 & ʿAbd Allā h b. Ahmad b. Hanbal, Kitāb al-Sunna, 213–14. ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 95-97 ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 51 & Abū Bakr al-Marrūdhı̄, al-Waraʿ, ed. Samı̄r al-Amı̄n al-Zuhayrı̄ (Riyadh: Dār al- S ̇umayʿı̄ , 1997), 131–5= (I did not have access to the following editions) ed. Muh ̇ammad al-Saʿı̄d Basyūnı̄ Zaghlūl (Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-ʿArabı̄, 1988) = ed.

Zaynab Ibrā hı̄ m al-Qā rū t ̇ (Beirut: Dā r al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya, 1983). ↩︎ - Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 229-230 & Al-Tirmidhı̄,ʿIlalal-Tirmidhı̄al-kabı̄r, arranged by Abū T ̇ālibal-Qād ̇ı̄ [Mahmūdb.ʿAlı̄ (d. 585/1189)], ed. Subhı̄ al-Sāmarrā’ı̄ , Abū al-Maʿātı̄ al-Nūrı̄ , and Mahmūd Muhammad Khalı̄ l al-Saı̄dı̄ (Beirut: ʿĀ lam al-Kutub/Maktabat al-Nahd ̇ a al-ʿArabiyya, 1989), 388. Al-Tirmidhı̄ wrote two works on this subject: al-ʿIlal al-kabı̄r (IK) and al-ʿIlal al-saghı̄r (IS). ̇ ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 229-230 & Muslimb.al-H ̇ajjāj,Kitābal-Kunāwaal-asmā’,ed.ʿAbdal-Rah ̇ı̄mMuh ̇ammadAh ̇mad al-Qashqarı̄ (Medina: Ihyā ’ al-Turā th al-Islā miyya, 1984), 276. ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 229-230 & Al-Nasā ’ı̄, Kitāb al-Duʿafā’ wa al-matrūkı̄n, 240 (laysa bi al-quwwa fı̄ al-hadı̄th). ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 229-230 & Al-Jū zajā nı̄ , Ahwā l al-rijā l, 75 ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 229-230 & Al-Dāraqutnı̄ , Sunan, 2: 107–8, 1: 223, 323 (al-Arna’ūtedn.); al-Sahmı̄ , Su’ālāt Hamza b. Yūsuf al-Sahmı̄lial-Dāraqutnı̄, 263, where we are informed that Abū Hanı̄fa’s hadı̄th transmissions were unreliable since he never met a Companion. ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 232 & ̇Al-ʿUqaylı̄, Kitāb al-Duʿafā’, 1: 36–8 (Dār al-Sumayʿı̄ edn.). ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 232-233 & Al-Jawraqānı̄, al-Abātı̄lwaal-manākı̄rwaal-sihāhwaal-mashāhı̄r, ed.ʿAbdal-Rahmān ̇ʿAbd al-Jabbā r al-Faryūwā ’ı̄ (Benares: Idā rat al-Buh ū th al-Islāmiyya wa al-Daʿwa wa al-Iftā ’, 1983), 2: 111, 170–1.) ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy pp. 323-324 Ibn Hibbān, Kitābal-Majrū ̇hı̄n, 2:405–6 (Riyadhedn.) ↩︎

- Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy p. 335 & Ibn Hibbān, Kitāb al-Majrūhı̄n, 3: 64 (Beirut edn.) = 2: 406 (Riyadh edn.)) ↩︎

One thought on “Abu Hanifa: The Heretic Who Became a Sunni Icon”