Abu Hanifa al-Nuʿmān ibn Thābit (699–767 CE / 80–150 AH) was a prominent Islamic scholar and jurist, best known as the founder of the Hanafi school of thought, the oldest and one of the most widely followed Sunni legal schools. Born in Kufa, Iraq, he was a merchant by trade but gained recognition for his deep knowledge of Islamic law, theology, and reasoning. He emphasized the use of independent reasoning (ra’y) and analogy (qiyas) in legal judgments, making his school particularly adaptable to diverse contexts.

However, it is well established that Abu Hanifa was criticized and condemned by early Sunni scholars because of his lack of emphasis on Hadith. Three of his most famous detractors were al-Bukhari, al-Shafi’i, and Ahmad ibn Hanbal. Bukhari considered Abu Hanifa as one of the worst things to have ever happened to Islam.

Below are excerpts from different works regarding the traditional Sunni despisement of Abu Hanifa as a heretic and cursed by Sunnis before his image was reframed by later scholars, most notably in the 10th and 11th centuries.

Hadith: Muhammad’s Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World

In the sixth chapter of Jonathan Brown’s book, Hadith: Muhammad’s Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World, it states:

“Even great scholars like Abū Hanīfa, who promoted using independent legal reasoning, were heretics in the eyes of these original Sunnis”

The Canonization of al-Bukhari and Muslim

In Jonathan Brown’s The Canonization of Al-Bukhari and Muslim, Brill 2007, it states on pp. 73-74:

Outside his Ṣaḥīḥ, however, al-Bukhārī’s disagreement with Abū Ḥanīfa and the ahl al-raʾy manifests itself in virulent contempt. He introduces his Kitāb rafʿal-yadayn fī al-ṣalāt as “a rebuttal of he (man) who rejected raising the hands to the head before bowing” in prayer and “misleads the non-Arabs on this issue (abhama ʿalā al-ʿajam fī dhālika) . . . turning his back on the sunna of the Prophet and those who have followed him. . . .” He did this “out of the constrictive rancor (ḥaraja) of his heart, breaking with the practice (sunan) of the Messenger of God, disparaging what he transmitted out of arrogance and enmity for the people of the sunan; for heretical innovation in religion (bidʿa) had tarnished his flesh, bones and mind and made him revel in the non-Arabs’ deluded celebration of him.” The object of this derision becomes clear later in the text, when al-Bukhārī includes a report of Ibn al-Mubārak praying with Abū Ḥanīfa. When Ibn al-Mubārak raises his hands a second time before bowing, Abū Ḥanīfa asks sarcastically, “Aren’t you afraid you’ll fly away? (mā khashīta an taṭīra?),” to which Ibn al-Mubārak replies, “I didn’t fly away the first time so I won’t the second.”

Ahmad b. al-Salt and his Biography of Abi Hanifa” by Eerik Dickinson

To combat this negative stigma towards Abu Hanifa, Hanafis, mostly in the 4th century Hijri, started writing musnads and biographies attributed to Abu Hanifa. In the article, “Ahmad b. al-Salt and his Biography of Abi Hanifa” by Eerik Dickinson (Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 116, No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 1996), pp. 406- 417)

“In the third/ninth century the adherents of hadith attacked Abu Hanifa for his apparent neglect of the hadith of the Prophet Muhammad in the formulation of doctrine. Around the beginning of the fourth/tenth century some Hanafites, including Ahmad b. al-Salt, started to write biographies and musnads which were aimed at establishing the credentials of the eponym of their school in the discipline of hadith. During his own lifetime, Ibn al-Salt was regarded as an unreliable scholar and this view was held by most later authorities. The Hanafites, however, found his representation of Abui Hanifa attractive and sought to preserve it by concealing its connection to him and by trying to salvage his reputation. Although these efforts were not successful, material from Ibn al-Salt continued to appear in the biographies of the imam.”

Other notable excerpts from this article can be found below, where it describes the accusations and condemnations made against Abu Hanifa. Much of his criticism came from his lack of emphasis on Hadith for his legal ruling, and centuries later, scholars attempted to revitalize his image by ascribing many Hadith mustards to his name.

Aḥmad B. al-Ṣalt and His Biography of Abū Ḥanīfa

Eerik Dickinson

Journal of the American Oriental Society

Vol. 116, No. 3 (Jul. – Sep., 1996), pp. 406-417 (12 pages)

Published By: American Oriental Society

https://www.jstor.org/stable/605146

Abu Yusuf (d. 182/798) was a prominent student of Abu Hanifa and chief judge (qadi) under the Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid. Below is a quote attributed to him regarding their view on transmitted reports (Hadith). It is worth noting that historically, the term sunnah was used for the living practice; however, over time, the term sunna and Hadith have become synonymous. Below is a quote from the article The Theory and Practice of Hadith Criticism in Mid-Ninth Century, p. 85, by Christoper Melchert.

Christopher Melchert, The Theory and Practice of Hadith Criticism in the Mid-Ninth Century, pp. 85-86

Ahmed El Shamsy has drawn attention to some brief comments on how to identify reliable hadith preserved near the beginning of Siyar al-Awzāʿī, apparently a polemic by Abū Yūsuf (d. 182/798?) against the Syrian jurisprudent al- Awzāʿī overlaid by polemics from al-Shāfiʿī.42 Abū Yūsuf quotes advice from the Prophet through the Shiʿi imam Muḥammad al-Bāqir (d. 114/732–733?), “Hadith will spread from me (yafshū ʿannī). What comes to you from me that agrees with the Qurʾān, it is from me. What comes to you from me that disagrees with the Qurʾān, it is not from me.”43 This is hadith criticism by content alone. More elaborately, Abū Yūsuf says himself,

The evidence for what our party (al-qawm) has brought forth is that hadith from the Messenger of God … and narration has increased in quantity. Some of what has transpired is unknown: it is unknown to qualified jurisprudents (ahl al-fiqh) and disagrees with the Book and the sunna. Beware of aberrant (shādhdh) hadith. Incumbent on you is widely-accepted hadith (mā ʿalayhi al-jamāʿa), what the jurisprudents recognize, and what agrees with the Qurʾān and sunna. Draw analogies from that. What disagrees with the Qurʾān is not from the Messenger of God …, even if there is a narration of it.44

43: Al-Shāfīʿī, al-Umm, ed. Rifʿat Fawzī ʿAbd al-Muṭṭalib, 11 vols (al-Manṣūra: Dār al-Wafāʾ, 1422/2001; 2nd printing 1425/2004), 9:187.

44 Shāfiʿī, Umm, 9:188–189. Cited in support of caution regarding hadith-based law today by Fazlur Rahman, Islamic Methodology in History, Central Institute of Islamic Research (Pakistan) 2 (Karachi: Central Institute of Islamic Research, 1965), 35.

The Canonization of Islamic Law by Ahmed El-Shamsy p. 51

Abu Yusuf notes that the number of available Hadith reports has increased greatly and argues that “those reports are to be excluded that are unknown or not known to jurists, as well as those that agree with neither the Quran nor the Sunna. And beware of irregular Hadith (shadhdh), and keep to those Hadith to which the community adheres and which the jurists know.”

Abu Yusuf in Siyar al-Awza’i, reproduced with comments in al-Shafi’i’s Umm, 9:188-89

Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy

Ahmad Khan very recently published a book on this subject, Heresy and the Formation of Medieval Islamic Orthodoxy, Cambridge University Press, 2023, tracking how Abu Hanifa went from being hated among proto-Sunni traditionalists, especially in the 8th and 9th centuries, to having his school of thought canonized as one of the four legal schools of Sunni Islam in the later 10th to 11th centuries. The remainder of the quotes in this article will be pulled from this book.

Three Stages of Views Towards Abu Hanifa by Sunnis pp. 24-25

In 1070 al-Khat ̇ı̄ b al-Baghdādı̄ was putting the final touches to his monumental biographical dictionary of over 7,831 scholars who had some connection to the sprawling metropolis of Baghdad. Written in the eleventh century, al-Khat ̇ı̄ b al-Baghdādı̄ ’s magnum opus represented the culmination and vast accumulation of historical information concerning the social and religious history of the eighth–eleventh centuries…Al-Khatı̄b al-Baghdādı̄’s vast collection of hostile reports concerning Abū Hanı̄fa provides an immediate sense of just how widespread discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa had been before the eleventh century. What it does not allow for, however, is a more precise knowledge of how attitudes to Abū Hanı̄fa changed over the course of the eighth–eleventh centuries; nor does it allow us to reconstruct the proto-Sunni traditionalist textualist community that promulgated discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa. In short, al-Khatı̄b al-Baghdādı̄ ’s entry on Abū Hanı̄fa is no substitute for a more careful examination, century by century, text by text, and author by author, of the evolution of discourses of heresy. In fact, relying exclusively, or even primarily, on the Tārı̄kh Baghdād risks distorting the history of discourses of heresy and orthodoxy within proto-Sunnism.

This chapter reveals the results of a thorough investigation into a large and diverse corpus of texts composed between the ninth and eleventh centuries of discourses of heresy concerning Abū Hanı̄fa. I have identified three distinct stages in the development of hostility towards Abū Hanı̄fa during these centuries. During the first stage (800–850) discourses of heresy towards Abū Hanı̄fa were sharp, but they were limited to specific criticisms. These criticisms tended to be confined to Abū Hanı̄fa’s legal views and his approach to hadı̄th. A more sustained and extensive discourse of heresy emerged only during the second stage (850–950). This period witnessed the emergence of a discourse of heresy designed to establish Abū Hanı̄fa as a heretic and deviant. It was, in my view, the very intensity of this discourse of heresy that occasioned a third shift (900–1000) in discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa. Proto-Sunni traditionalists now began to engender a more accommodating attitude towards Abū Hanı̄fa. This formed the groundwork for the wide embrace of Abū Hanı̄fa among the proto-Sunni community, culminating in his consecration as a saint-scholar and one of the four representatives of Sunni orthodoxy in medieval Islam.

Early Views on Abu Yusuf (d. 182/798) & Hadith p. 33

Abū Yūsuf al-Qādı̄: He has many hadı̄th on the authority of Abū Khusayf, Mughı̄ra, Husayn, Mutarrif, Hishām b. ʿUrwa, al-Aʿmash, and others amongst the Kufans. He was known for his memorisation of hadı̄th . . . then he adhered closely (lazima) to Abū Hanı̄fa, learnt jurisprudence (tafaqqaha) from him, and speculative jurisprudence (ra’y) overcame him (ghalaba). Consequently, he turned away (jafā ) from hadı̄th.

Ibn Saʿd, T ̇ abaqāt al-kubrā, 7: 330

Ibn Abı̄ Shayba (d. 235/849) views on Abu Hanifa p. 35-36

There is, also, the curious inclusion of one of the longest books, ‘The Refutation of Abū Hanı̄fa’. The book does not deviate substantially from the style and format of the Musannaf‘s other chapters. It is introduced ̇with a sentence explaining that it describes all the instances in which Abū Hanı̄fa opposed reports (al-athar) that were transmitted from the Messenger of God. Ibn Abı̄ Shayba presents a total of 485 reports which he believes Abū Hanı̄fa contravened. The first report concerns the stoning to death of Jewish men and women and takes the following format:52

- Sharı̄k b. ʿAbd Allāh < Samāk < Jā bir b. Samura: the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, stoned a Jewish man and a Jewish woman.

- Abū Muʿāwiya and Wakı̄ ʿ < al-Aʿmash < ʿAbd Allāh b. Murra < al-Barā’ b. ʿĀzib: the Messenger of God, God pray over him and grant him peace, stoned a Jewish man.

- Ibn Numayr < ʿUbayd Allāh < Nāfiʿ < Ibn ʿUmar: the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, stoned two Jews, and I was among the people who stoned them both.

- Jarı̄r < Mughı̄ra < al-Shaʿbı̄: the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, stoned a Jewish man and a Jewish woman.

- It is reported that Abū Hanı̄fa said: ‘They are not to be stoned.’

The remaining 484 reports assume this very style of argumentation. The final report in Ibn Abı̄ Shayba’s refutation of Abū Hanı̄fa reads:53

- Abū Khālidal-Ahmar < Yahyā b.Saʿı̄d < ʿAmrb.Yahyā b.ʿUmāra < his father < Abı̄ Saʿı̄d said: the Messenger of God, God pray over him and grant him peace, said: ‘No charity (sadaqa) is due on anything less than five aswāq.’

- Abū Usāma < Walı̄d b. Kathı̄r < Muhammad b. ʿAbd al-Rahmāṅ b. Abı̄ Saʿ ̇saʿa < Yah ̇ yāb. ʿUmāra and ʿIbād b. Tamı̄m < Abı̄ Saʿı̄d al-Khudrı̄ : he heard the Messenger of God, God pray over him and grant him peace, say: ‘There is no charity due on anything less than five aswāq of dates.’

- ʿAlı̄ b. Ishāq < Ibn Mubārak < Maʿmar < Suhayl < his father < Abū Hurayra: The Prophet of God, God pray over him and give him peace, said: ‘There is no charity due on anything less than five aswāq.’

- It is reported that Abū Hanı̄fa said: ‘Charity is due on anything that exceeds or is less than this.’

Despite the steady pattern of this kind of criticism against Abū Hanı̄fa, there are some alterations in the specific wording Ibn Abı̄ Shayba chooses to describe Abū Hanı̄fa’s contravention of Prophetic reports. We saw in the first report, for example, that Ibn Abı̄ Shayba described Abū Hanı̄fa’s legal views as being in direct contradiction to the Prophet’s: where the Prophet stoned a Jewish man and woman, Abū Hanı̄fa ruled that they should not be stoned (laysa ʿalayhimā rajm). This seems to represent the most frequent technique for describing Abū Hanı̄fa’s opposition to Prophetic hadı̄th. Ibn Abı̄ Shayba has Abū Hanı̄fa provide a legal opinion that is contrary to the one adumbrated by his selection of Prophetic reports. But there are other stock phrases Ibn Abı̄ Shayba employs. When the Prophet forbade prayer in the resting places of camels, Abū Hanı̄fa declared that doing otherwise was not a problem (lā ba’s bi dhālika). This specific phrase – lā ba’s bi dhālika – appears in reports than five aswāq.’ 2. Abū Usāma < Walı̄d b. Kathı̄r < Muhammad b. ʿAbd al-Rahmān concerning the permissibility of travelling with the Quranic mushaf to enemy lands (al-safar bi al-mushaf ilā ard al-ʿadūw)54; giving equally among one’s offspring (al-taswiya bayna al-awlād fı̄ al-ʿatı̄ya);55 on the prohibition of inheriting wine even if one intends to turn it into vinegar;56 and many others. In other reports Abū Hanı̄fa is described as having opined against the verdict of a Prophetic hadı̄th (qāla bi khilāfihi).57

52: Ibn Abı̄ Shayba, al-Musannaf, ed. Muhammad ʿAwwā ma (Jeddah: Dār al-Qibla li al-Thaqā fa al-Islā miyya, 2006), 20: 53–4 = (Hyderabad: al-Ma ̇tbaʿa al-ʿAzı̄ ziyya, 1966), 14: 148–9.

53: Ibn Abı̄ Shayba, al-Musannaf, 20: 216–17 = 14: 281–2. ̇

54: Ibn Abı̄ Shayba, al-Musannaf, 20: 58–9 = 14: 151–2.

55: ̇ Ibn Abı̄ Shayba, al-Musannaf, 20: 59–60 = 14: 152–3.

56: ̇Ibn Abı̄ Shayba, al-Musannaf, 20: 90 = 14: 178.

57: ̇Ibn Abı̄ Shayba, al-Musannaf, 20: 104 = 14: 188–9.

Sahih al-Bukhari (d. 256/870) & Abu Hanifa (baʿd al-nās) p. 45

It seems plausible that al-Bukhārı̄ was framing his Sahı̄h ̇against proto-Hanafı̄s and, in doing so, he was explicitly imitating the method and practice of his teacher, al-Humaydı̄.

Al-Humaydı̄’s influence over al-Bukhārı̄’s hostility towards Abū Hanı̄fa can be discerned elsewhere. In medieval and modern Arabophone scholarship, much has been made of al-Bukhārı̄ ’s twenty-five references to ‘some people’ (baʿd al-nās) in the Sahı̄h.30 It has been pointed out that ̇ al-Bukhārı̄’s use of the moniker baʿ ̇d al-nās did not always imply Abū Hanı̄fa and was intended to denote rationalists and semi-rationalists such 31

as ʿIsā b. Abān, al-Shāfiʿı̄ , and al-Shaybānı̄ . Sunni traditionalists of the tenth century believed that the practice of employing oblique references to Abū Hanı̄fa as a veiled barb preceded al-Bukhārı̄. Ibn Hibbān (d.354/965) writes:32

I heard al-Hasan b. ʿUthmān b. Ziyā d < Muhammad b. Mansūr al-Jawwār say: I saw al-Humaydı̄ reading the Book of Refutation against Abū Hanı̄fa in the sacred mosque, and I noticed that he would say: ‘Some people say such and such.’ I asked him, ‘Why do you not mention them by name?’ He replied, ‘I dislike mentioning them by name in the sacred mosque.’

The historiographical obsession with al-Bukhārı̄ and the canonisation of his Sahı̄h has contributed to the overshadowing of his teachers and influences. In this and other respects, al-Bukhārı̄’s condemnation of Abū Hanı̄fa as a heretic and deviant owed much to al-Humaydı̄ ’s leadership.

Sahih al-Bukhari (d. 256/870) & Abu Hanifa (baʿd al-nās) p. 46

Proto-Sunni traditionalists were creating a mode of speech and discourse against Abū Hanı̄fa unique to their network. In using baʿ ̇d al-nās in this particular fashion, al-Bukhārı̄ and al-Humaydı̄ were speaking the language of their group. The decision to employ a generic term and not Abū Hanı̄fa’s name was a conscious one and, as al-Humaydı̄ ’s earlier remark shows, this was probably not an indication of reverence. p. 46

Abū Zurʿa al-Rā zı̄ (d. 264/878) p. 46

Abū ̇Zurʿa al-Rāzı̄ remembered al-Humaydı̄’s lessons wherein he read from The Refutation against al-Nuʿmān:36

The people of Rayy had become corrupted by Abū Hanı̄fa. We were young men, and we fell into this along with the rest of the people of Rayy. It got to a point where I asked Abū Nuʿaym about this, and it led me to realise that I had to do something. Al-Humaydı̄ used to read [to us] The Refutation and refer to Abū Hanı̄fa, and I also began to attack him; until, finally, God granted us favour, and we came to realise the deviation of the people.

36: Ibn Abı̄ Hātim, al-Jarh, 4.1: 40 (kāna ahl al-rayy qad uftutina bi Abı̄ Hanı̄fa, wa kunnā a ̇hdāthan najrı̄ maʿahum, wa la qad sa’altu Abā Nuʿaym ʿan hādhā, wa anā arā annı̄ fı̄ ʿamal. Wa la qad kāna al-Humaydı̄ yaqra’u Kitāb al-Radd wa yadhkuru Abā Hanı̄fa, wa anā ahummu bi al-wuthūb ʿalayhi ̇hattā manna Allāh ʿalaynā wa ʿarafnā ̇dalāta al-qawm).

Shafi’i (d. 204/820) Against Abu Hanifa & al-Ray p. 47

One might suppose that al-Humaydı̄ was inspired by his teacher, al-Shāfiʿı̄ , to compose The Refutation against al-Nuʿmān. Ibn Abı̄ Hātim is again the source for a report that has al-Humaydı̄ express his gratitude for al-Shāfiʿı̄’s intervention against the ashāb al-ra’y: ‘We desired to refute the ashāb al-ra’y but we did not know how best to refute them until al-Shāfiʿı̄ came to us and showed us the way.’ 37 However, ascribing this motive to al-Humaydı̄’s authorship of a book 38 condemning Abū Hanı̄fa may be too kind to pro-Shāfiʿı̄ sources.

Abū Bakr al-Marrūdhı̄ (d. 275/888) pp. 50-51

Abū Bakr al-Marrūdhı̄ (d. 275/888) – another crucial contributor to discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa whose views we shall survey in this chapter – in his Kitāb al-Waraʿ presents the following account of Ishāq b. Rāhawayh’s dramatic volte-face:49

I used to be an adherent of speculative jurisprudence (sāhib ra’y). When I decided ̇to embark on the greater pilgrimage (al-hajj), I studied deeply the books of ʿAbd Allāh b. Mubārak. I found therein close to three hundred hadı̄ th which agreed with the jurisprudence of Abū Hanı̄fa (mā yuwāfiq ra’y Abı̄ Hanı̄fa). I asked ʿAbd Allā h b. Mubārak’s teachers in the Hijā z and in Iraq about them, and not for a moment did I think that any person would dare oppose Abū Hanı̄fa. When I arrived in Basra, I went to study with (jalastu ilā ) ʿAbd al-Rahmān b. Mahdı̄ .

During their first meeting, the following conversation ensued between teacher and student:

ʿAbd al-Rahmān b. Mahdı̄: Where are you from?

Ishāq b. Rāhawayh: I am from Marw.

Ishāq b. Rāhawayh: Upon hearing of this [that Ishāq hailed from the same region as Ibn al-Mubārak], ʿAbd al-Rahmān b. Mahdı̄ prayed for God’s mercy to descend upon (fa tara ̇h ̇hama ʿalā) Ibn al-Mubārak. He loved him a great deal (wa kāna shadı̄d al- ̇hubb lahu). He then asked me whether I could recite an elegy (marthiya) to celebrate him. ‘Yes,’ I replied, and I recited the elegy of Abū Tamı̄la Yahyā b. Wādih al-Ansārı̄. Ibn al-Mahdı̄ could not stop weeping as I was reciting the elegy, but he stopped abruptly when I recited: ‘ … and with the jurisprudence of al-Nuʿmān you [i.e. Ibn al-Mubārak] acquired knowledge and insight . . . ‘

Abd al-Rahmān b. Mahdı̄: Enough! You have sullied the elegy (uskut! qad afsadta al-qası̄da).

Ishāq b. Rāhawayh: But there are some wonderful verses that follow this.

ʿAbd al-Rahmān b. Mahdı̄: Forget them. How dare you mention ʿAbd Allāh’s transmission from Abū Hanı̄fa in the course of an elegy! Do you not know that for ʿAbd Allāh there is nothing more debased than the dirt of Iraq than his transmitting from Abū Hanı̄fa? How I wish he had not transmitted from him (law wadadtu annahu lam yarwi ʿanhu)! How I would have ransomed a great portion of my wealth to have ensured that (wa innı̄ kuntu aftadı̄ dhālika bi ʿa ̇zm mālı̄)!

Ishāq b. Rāhawayh: O Abū Saʿı̄d,why are you so critical of Abū Hanı̄fa (lima ta ̇hmil ʿalā Abı̄ Hanı̄fa kull hādhā)? Is it because he would employ forms of speculative jurisprudence (yatakallamu bi al-ra’y)? Well, Mālik b. Anas, al-Awzāı̄, and Sufyān all employed forms of speculative jurisprudence.

ʿAbd al-Rahmān b. Mahdı̄: I see, so you consider Abū Hanı̄fa to be in the same league as these people (taqrunu Abā Hanı̄fa ilā hā’ulā’)? Abū Hanı̄fa did not resemble these people in learning except in that he was a lone, deviant she-camel grazing in a fertile valley whilst all the other camels were grazing in a different valley altogether (mā ashbaha Abā Hanı̄fa fı̄ al-ʿilm illā bi nāqa shārida fārida turʿā fı̄ wādı̄ khasb wa al-ibl kulluhā fı̄ wādı̄ ākhar).

Ishāq b. Rāhawayh: After this, I started to reflect more deeply and discovered that the people’s view of Abū Hanı̄fa’s [orthodox] standing was completely at odds with what we in Khurāsān believed about him (fa idhā al-nās fı̄ amr Abı̄ Hanı̄fa ʿalā khilāf mā kunnā ʿalayhi bi Khurāsān).

Ibn Qutayba (d. 276/889) pp. 55-56

Ibn Qutayba does not reproduce all of Ishāq b. Rāhawayh’s criticisms, but he does relate Ishāq b. Rāhawayh’s dismay at the legal doctrines of the ashāb al-ra’y: their legal views concerning the ̇consequences of laughter during the prayer; the inheritance of grandchildren from their grandfather if their fathers death precedes that of their grandfather; Abū Hanı̄fa’s position on raising the hands during the prayer; Abū Hanı̄fa’s ruling that it is permissible to drink from silver vessels;65 and many other legal doctrines associated with Abū Hanı̄fa. Ishāq b. Rāhawayh was out spoken against Abū Hanı̄fa and his followers, and Ibn Qutayba states explicitly that were it not for the fact that the book would become too long he would have documented them all.66

Al-Bukhārı̄ (d. 256/870) pp. 57-58

Al-Bukhārı̄’s condemnation of Abū Hanı̄fa is discussed in more than one place in this study. Chapter 5 contains an extensive treatment of al-Bukhārı̄ ’s discourse of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa and its relationship to ethnogenesis in early Islamicate societies. That section examines al-Bukhārı̄’s deprecation of Abū Hanı̄fa in his Kitāb Rafʿal-yadayn fı̄ al- ̇salāt. Since Chapter 3 is concerned with examining the role that ethnogenesis had in discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa, al-Bukhārı̄ ’s biography and his upbringing are described in detail there. This section studies discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa and his followers in al-Bukhārı̄’s al-Tārı̄kh al-kabı̄r, al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat,74 al-Jāmiʿal-Sahı̄h, and Kitāb Khalq afʿāl al-ʿibād…

Al-Bukhārı̄ (d. 256/870) p. 59

Let us consider, for example, al-Bukhārı̄ ’s deployment of the moniker baʿ ̇d al-nās for Abū Hanı̄fa and his disciples. We learned earlier that this label was shot through with subversive undertones and that it originated with al-Bukhārı̄ ’s teacher, al-Humaydı̄. Al-Bukhārı̄ ’s Sahı̄h contains references to Mālik b. Anas, al-Shāfiʿı̄ , and Ahmad b. Hanbal.77 Abū Hanı̄fa is not mentioned by name throughout the Sahı̄h. Mālik b. Anas, al- Shāfiʿı̄ , and Ahmad b. Hanbal are all referred to by al-Bukhārı̄ on account either of their legal opinions or their transmissions of hadı̄th. Al-Bukhārı̄ ’s baʿ ̇d al-nās moniker for Abū Hanı̄fa is reserved exclusively for cases where al-Bukhārı̄ describes an opposing position. He cites baʿ ̇d al-nās on twenty-seven occasions. Abū Hanı̄fa and his followers were natural targets for al-Bukhārı̄’s section on legal tricks (kitāb al-hiyal).78 This book alone contains fourteen references to baʿ ̇d al-nās.79 ̇It opens with the same theme and hadı̄th report (with slight variations) with which al- Bukhārı̄ opens his Sahı̄h:

The chapter on abandoning legal tricks and that for every person is that which he intends with respect to oaths and other things. Abū al-Nuʿmān < Hammād b. Zayd < Yahyā b. Saʿı̄d < Muhammad b. Ibrāhı̄m < ʿAlqama b. Waqqā ̇s said: ‘I heard ʿUmar b. al-Khat ̇tāb as he was giving a sermon say: “I heard the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, say: ‘O people. Actions are by intentions only. A man only obtains that which he intends. Whosoever’s migration was to (and for) God and His Messenger, then his migration was to God and His Messenger. Whosever migrated for this world seeking to obtain something of it, or for the sake of marrying a woman, then his migration was for the sake of that which he migrated.’”’

At one point in the book on legal tricks al-Bukhārı̄ drops this equivocating manner of criticising Abū Hanı̄fa and hisfollowers:80

The chapter on gifts and pre-emption. Certain persons have said: if someone gifts a gift of one hundred dirhams or more, and this gift has remained with the person for many years and the giver seeks a legal trick and then the gift-giver seeks to retrieve the gift, then there is no zakāt due on either of the two. He/they has opposed the messenger, God pray over him and grant him peace, in the matter of gifts; and he has eliminated [the obligation of] zakāt (fa khālafa al-rasūl ̇sallā Allāhu ʿalayhi wa sallama fı̄ al-hiba wa asqata al-zakāt).

We see here a rapid transition of tone and style in the Sahı̄h. Al-Bukhārı̄ accuses his interlocutor of opposing the Messenger in relation to the issue of gifts and he insists that his opponent’s doctrine amounts to nothing less than vitiating altogether the obligation of zakāt. It is the shift in al- Bukhārı̄ ’s mode of argumentation that adds weight to the view that baʿ ̇d al-nās was a reference to Abū Hanı̄fa and his followers, and that it was one that al-Bukhārı̄ invoked whenever he sought to discredit proto-Hanafı̄ s and their eponymous founder.

Al-Bukhārı̄ (d. 256/870) p. 63

In the light of the scarce background information on al-Bukhārı̄’s interactions with proto-Hanafı̄s, we can turn directly to al-Bukhārı̄’s Histories to examine his contribution to discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa. Al-Bukhārı̄ composed three Histories: al-Tārı̄kh al-kabı̄r, al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat ̇ (Kitāb al-Mukhtasar), and al-Tārı̄kh al-saghı̄r. The first two have survived, ̇but the third is no longer extant. Al-Bukhārı̄ also dedicated two works to the history of weak hadı̄th scholars: Kitāb al-Duʿafā’ al-kabı̄r and Kitāb al-Duʿafā’ al-saghı̄r. The former is lost, whilst the latter has been published.96 There are attacks on Abū Hanı̄fa and his students across all of these published works. Al-Bukhārı̄’s al-Tārı̄kh al-kabı̄r devotes an entry to Abū Hanı̄fa. He dismisses Abū Hanı̄fa as belonging to a movement which proto-Sunni traditionalists deemed to be heretical, the Murji’a. He further explains that the scholarly community renounced (sakatū ʿanhu) Abū Hanı̄fa, his speculative jurisprudence, and his hadı̄th.97

97 Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Tārı̄kh al-kabı̄r, 4.2: 81.

Al-Bukhārı̄ (d. 256/870) pp. 64-65

Al-Bukhārı̄ states that Muhammad b. Maslama once related that someone remarked to him, ‘What is the business with Abū Hanı̄fa’s speculative jurisprudence? It entered every single town save Medina.’ To this, Muhammad b. Maslama replied: ‘He [Abū Hanı̄fa] was one of the anti-Christs, and the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, said that neither the plague nor the anti-Christ shall enter Medina.’100 p. 64

Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Tārı̄kh al-kabı̄r, 1.1:240.

Nuʿaym b. Hammād < al-Fazārı̄ said: ‘I was with Sufyān when news of al-Nuʿmān‘s death arrived. He said: “Praise be to God. He was destroying Islam systematically. No one has been born in Islam more harmful than he [was].”’ – p.65

Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat, 4:503 (Abū Haymadedn) = 2:77 (al-Luhaydānedn)

Al-Bukhārı̄ (d. 256/870): No Salawat Upon the Prophet by Abu Hanifa p. 66

Whenever I wanted to see Sufyān, I saw him praying [upon the Prophet] or narrating hadı̄th, or engaged in abstruse matters of law (fı̄ ghā mi ̇d al-fiqh). As for the other gathering that I witnessed, no one prayed upon the Prophet in it.

The narrator, Ibn al-Mubārak, fails to mention the name of the scholar who convened the study-circle. However, al-Bukhārı̄ claimed to know exactly to whom Ibn al-Mubārak was referring. He adds at the end of this report, ‘he means [the gathering of] al-Nuʿmān’.106 Al-Bukhārı̄ is concerned with portraying the lack of basic religious piety in the study-circles of Abū Hanı̄fa. The report he cites is at pains to demonstrate that proto- Sunni traditionalists did not simply attack Abū Hanı̄fa for his speculative and casuistic jurisprudence. Abū Hanı̄fa was not the only scholar committed to tackling obscure legal conundrums. This was the inveterate practice of Sufyān al-Thawrı̄ , too. However, Sufyān al-Thawrı̄ ’s religious teaching sessions were characterised by the elementary norms of Muslim piety: he was either invoking blessings and prayers upon the Prophet or transmitting his words and deeds. According to his critics, these pietistic conventions were conspicuous by their absence in Abū Hanı̄fa’s study sessions.

106 Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat, 2:113–14 (al-Luhaydānedn)

Abu Hanifa and Salawat p. 242

On lookers observed that when Abū Hanı̄fa was presiding over lessons in the mosque there would be laughter and people would be raising their voices.158 Others were affronted by more serious charges, namely, that Abū Hanı̄fa’s lessons would go on without their being any praise for the Prophet Muhammad.159

– ʿAbd Allā h b. Ahmad b. Hanbal, Kitāb al-Sunna, 213–14.

Al-Bukhārı̄ (d. 256/870): Abu Hanifa Didn’t Know Basic Practices of Hajj p. 67

Al-Bukhārı̄ transmits the following story in his al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat:107

I heard al-Humaydı̄ say: Abū Hanı̄fa said: ‘I came to Mecca and took from the cupper (al- ̇hajjām) three sunan. When I sat in front of him, he said to me: “Face the Kaʿba.” Then he began to shave the right side of my head and reached the two bones.’

Al-Humaydı̄ said: ‘How is it that a man who does not possess [knowledge of the] practices (sunan) of the Messenger of God, nor of the Companions, with regard to the rituals of pilgrimage (al-manāsik) and other things, can be followed in the commandments (a ̇hkām) of God concerning inheritance and other obligatory elements, [such as] prayer, alms-giving, and the rules of Islam?’

The source of al-Bukhārı̄ and al-Humaydı̄ ’s outrage seems to be that Abū Hanı̄fa had to receive instructions from a cupper as to some of the basic rituals pertaining to the pilgrimage. Al-Humaydı̄ could not fathom why someone who was unfamiliar with the rituals of pilgrimage could be considered an authority and worthy of imitation with respect to any sphere of religious obligation. There is no attempt by proto-Sunni traditionalists to provide a wider background and context to the alleged anecdote about Abū Hanı̄fa. This certainly reads as a disjointed report, one dislodged from a broader narrative. Proto-Sunni traditionalists displayed no interest, for example, in entertaining the possibility that the anecdote referred to a pilgrimage Abū Hanı̄fa had undertaken as a young man.108 This narration alone, regardless of its wider context, constituted further evidence for the proto-Sunni traditionalist belief that Abū Hanı̄fa could not be regarded as an exemplary figure of proto-Sunni orthodoxy.

107 Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Tārı̄khal-awsat, 3:382 (Abū Haymadedn.) = 2:37–38 (al-Luhaydān edn.). See also Yahyā b. Maʿı̄n, al-Tārı̄kh (al-Dū rı̄’srecension), ed. Ahmad Muhammad Nūr Sayf (Mecca: Markaz al-Bahth al-ʿIlmı̄ wa Ihyā ’ al-Turā th al-Islā mı̄ , 1979), 2: 607.)

Al-Bukhārı̄ (d. 256/870): Celebrating Abu Hanifa’s Death pp. 67-68

Our final example of al-Bukhārı̄’s discourse of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa in this section comes from his Kitāb al-Duʿafā ’ al-saghı̄r. Al-Bukhārı̄ ’s brief history of unreliable scholars is concerned with documenting the unreliability of scholars involved in the transmission or learning of hadı̄th.109 Scholars are dismissed for various reasons. Al-Bukhārı̄ brands certain scholars as inveterate liars.110 Others are discredited because of their association with heresies.111 However, al-Bukhārı̄ appears to give Abū Hanı̄fa special treatment. His entry on Abū Hanı̄fa relates three damning reports attacking Abū Hanı̄fa’s religious credibility. The first report maintains that Abū Hanı̄fa repented from heresy twice. The second report states that when Sufyān al-Thawrı̄ heard that Abū Hanı̄fa had passed away, he praised God, performed a prostration (of gratitude), and declared that Abū Hanı̄fa was committed to destroying Islam systematically and that nobody in Islam had been born more harmful than he. The third and final report, which al-Bukhārı̄ also includes in his al-Tārı̄kh al-kabı̄r, describes Abū Hanı̄fa as one of the anti-Christs.112

Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Duʿafā’ al-saghı̄r, ed. Abū ʿAbd Allā h Ahmad b. Ibrāhı̄m b. Abı̄ al-ʿAynayn (n.p.: Maktabat Ibn ʿAbbā s, 2005), 132

Ibn Qutayba (d. 276/889): Sunnis Loath Abu Hanifa Because He Rejects Hadith Rulings p. 74

We do not loathe (lā nanqimu) Abū Hanı̄fa because he employs speculative jurisprudence, for all of us to do this (kullunā yarā). However, we loathe him because when a hadı̄th comes to him on the authority of the Prophet, God pray over him and grant him peace, he opposes it (yukhālifuhu) in preference for something else. p.74

Ibn Qutayba, Ta’wı̄l mukhtalif al-hadı̄th, 63 (Zakı̄ al-Kurdı̄edn.)

This explanation paves the way for a series of examples whereby Ibn Qutayba demonstrates what he perceives to be Abū Hanı̄fa’s disregard for Prophetic hadı̄th.140 Ibn Qutayba then gives ample space to Ishāq b. Rāhawayh’s censure of Abū Hanı̄fa, where he describes seven instances of Abū Hanı̄fa’s ‘unforgivable opposition to the Quran and unforgivable opposition to the Messenger of God, upon one’s having been acquainted with his statement’.141 p.74

Ahmad Ibn Hanbal (d. 241/855) & Abd Allah b. Ahmad b. Hanbal (d. 290/903): Abu Hanifa Heresies pp. 95-97

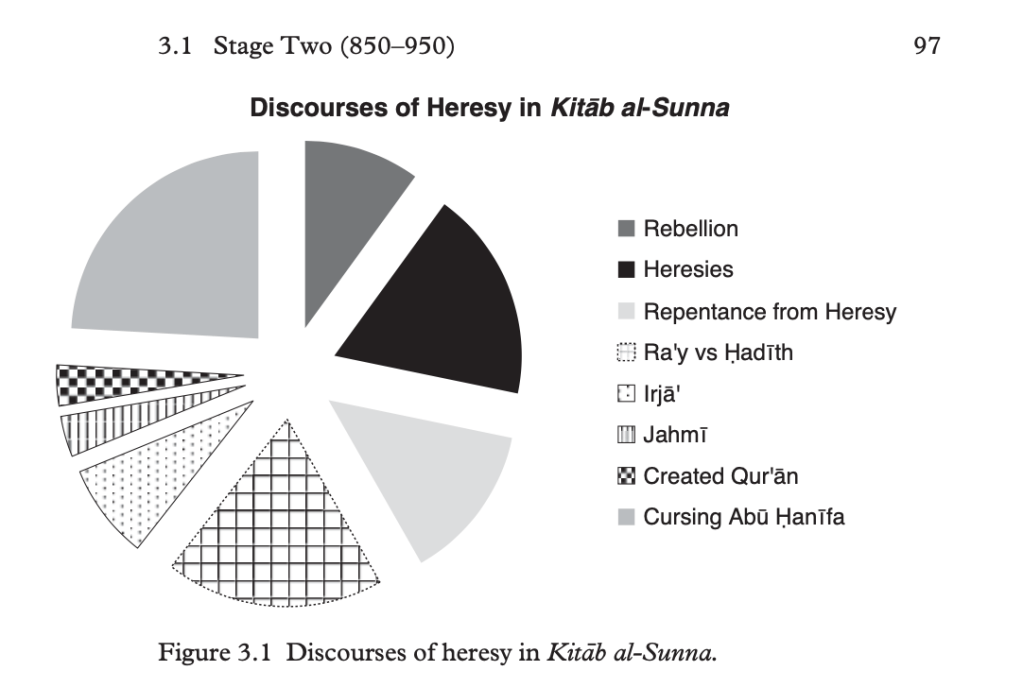

As we shall see in our analysis of discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa in the Kitāb al- Sunna, Ahmad b. Hanbal found the idea of rebelling against the state not only repugnant but a sign of heresy. In circumstances such as these, Ibn Hanbal believed that men could speak truth to power, but a more brazen challenge to the caliphal office was unconscionable. Within a year of Ahmad b. Nasr’s execution, change was in the air. Al-Mutawakkil had ascended the throne. Caliphal interest in pursuing the Mihna went from waning to a complete reversal. Ahmad b. Hanbal was now receiving invitations to visit the caliph in Samarra.252 These dramatic events and turbulent changes must have been stirring in ʿAbd Allāh’s mind when he began to compose the Kitāb al-Sunna. But proto-Sunni traditionalist conceptions of orthodoxy were not limited to debates concerning the createdness of the Quran. Other themes that appear prominently in the Kitāb al-Sunna are Irjā ’, the nature of faith (performance, action, or both), destinarianism, the probity of the first four caliphs, and attitudes to the state. But we can measure the importance of discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa to proto-Sunni traditionalists by the fact that ʿAbd Allāh’s Kitāb al-Sunna devotes almost fifty pages to portraying Abū Hanı̄fa as a heresiarch.253 ʿAbd Allāh’s method for depicting Abū Hanı̄fa as a heretic and deviant observes the norms of religious authority current among proto-Sunni traditionalists of the ninth century. Rather than communicating his own thoughts and ideas about Abū Hanı̄fa, ʿAbd Allāh proposes to relate information he heard from a select group of religious authorities…

The Kitāb al-Sunna evidences a number of themes that form the basis of discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa (see Figure 3.1). I have counted a total number of 184 anti-Abū Hanı̄fa reports in this section of the Kitāb al-Sunna. There are six overarching (and overlapping) themes in the material ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal collects against Abū Hanı̄fa. Most of the (forty-one) reports fall into the category of general curses against Abū Hanı̄fa. Within this category we have reports describing Abū Hanı̄fa as the greatest source of harm to Islam and Muslims; the most wretched person to be born in the religion of Islam; prayers and curses against Abū Hanı̄fa; and expressions of joy at the news of his death. The second prominent theme is the opposition between Abū Hanı̄fa’s ra’y and Prophetic hadı̄th (thirty-two reports). This is followed closely by the theme of heresies (thirty-one reports). This category refers to reports wherein the semantic field of heresy (kufr, kāfir; zandaqa, zindı̄q; murūq, mā riq, etc.) is employed against Abū Hanı̄fa. Examples of reports from this category include a report in which a proto-Sunni traditionalist encouraged his colleague to declare Abū Hanı̄fa an unbeliever (kāfir)

and heretic (zindı̄q) because he believed the Quran to be created;255 students of Mālik b. Anas alleged that he declared Abū Hanı̄fa to be beyond the pale of the religion;256 on a separate occasion, when someone proposed one of Abū Hanı̄fa’s solutions to a legal question, it was dismissed curtly as the view of ‘that apostate’.257 The fourth theme refers to reports that describe Abū Hanı̄fa as having repented publicly from heresy (twenty-three reports). Another prominent theme is rebellion (seventeen reports). ʿAbd Allāh collects reports in which proto-Sunni traditionalists drew attention to the heretical nature of Abū Hanı̄fa’s support for rebellion against Muslim rulers. A sixth theme is Abū Hanı̄fa’s adherence to the heresy of Irjā’ (fourteen reports). Little is made of Abū Hanı̄fa’s views on the Quran (six reports) and his connection to the Jahmiyya (six reports), which is especially surprising given the historical background of the Mihna and the involvement of the author’s father, Ahmad b. Hanbal, in that inquisition. There is no doubt that the Kitāb al-Sunna represented the culmination of proto-Sunni traditionalist attempts to place Abū Hanı̄fa outside the realm of orthodoxy and that the close students of Ahmad b. Hanbal were at the forefront of disseminating discourses of heresy against Abū Hanı̄fa. – p.95-97

Raising Hands in Salat p. 171-173

These are the first lines of al-Bukhārı̄ ’s book regarding the performance of the ritual prayer and the obligation, according to al-Bukhārı̄ , that one raise one’s hand during the takbı̄rāt:68

[This book is] A refutation of him who rejected raising the hands in the ritual prayer before bowing and upon raising his head after the cycle of prostration. He confused the non-Arabs on this issue out of his endeavour to disregard utterly that which was established from the Messenger of God of his actions and sayings; and he had the same disregard for that which was established from the actions of his Companions and their narrations; and then the generation of the Successors and the adherence of the pious ancestors to them with respect to narrations that had been authenticated, transmitted from one reliable authority to another from the upright generation that came after, may God be pleased with them all and may He grant them what He has promised them. [And this was all done] out of the spitefulness of his breast, the rancour of his heart, departing from the practices of the Messenger of God, showing contempt for what he transmitted out of his arrogance and enmity for its people [ahl al-sunan], because heresy had contaminated his flesh, bones, and mind and made him delight in the non-Arabs’ misguided celebration of him.

In order to illustrate the disparity between orthodoxy and heresy, al-Bukhārı̄ cites an incident involving Abū Hanı̄fa which by the ninth century had become widespread:71

ibn al-mubā rak: I was praying next to al-Nuʿmān [b. Thābit] and I raised my hands.

abū hanı̄fa [after the prayer had finished, as another source tells us]: Did you not fear that you would fly?

ibn al-mubā rak: If I did not fly away the first time I raised my hands at the opening takbı̄r of prayer, why would I fly away the second time?

Sunnis Celebrated the Death of Abu Hanifa p. 195

We read in al-Bukhārı̄’s al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat that al-Fazārı̄ said: ‘I was with Sufyān when the news of al-Nuʿmān’s [b. Thābit] death came. He said: “Praise be to God. He was destroying Islam systematically. No one was born in Islam more accursed than him.”’42

42 Al-Bukhārı̄, al-Tārı̄kh al-awsat [Kitāb al-Mukhtasar], 3: 503 (Abū Haymad edn.)

Sunnis Celebrated the Death of Abu Hanifa p. 242

In the case of Abū Hanı̄fa, proto-Sunni traditionalists purported to document the instant reactions of leading members of their textual community to the news that Abū Hanı̄fa had passed away. When Sufyān al-Thawrı̄ heard the news of Abū Hanı̄fa’s death, proto-Sunni traditionalists of the ninth century reported him as having exclaimed: ‘Praise be to God who has relieved the Muslims of him [Abū Hanı̄fa]. He had been destroying systematically the foundations of Islam. No birth was more harmful (ash’am) to Islam than his.’160 The same is reported on the authority of Mālik b. Anas: ‘No one was born in Islam whose birth was more harmful to the Muslims than that of Abū Hanı̄fa.’ The report continues:

Mālik b. Anas would condemn speculative jurisprudence. He would say, ‘We must adhere to the reports of the messenger of God, may God bless him and grant him peace, and the reports of his Companions. We cannot adhere to speculative jurisprudence, for it produces a situation whereby if someone comes along who is stronger in speculative jurisprudence, then one must adhere to him. We would have a situation whereby whenever someone comes along who displays a stronger grasp of speculative jurisprudence than you, you would be forced to follow him. The matter would continue in this [absurd] manner.’161

We find al-Fasawı̄’s history again cited the following view: ‘No one initiated more evil in Islam than Abū Hanı̄fa except so and so who was crucified.’162

161 Al-Fasawı̄, Kitāb al-Maʿrifa wa al-tārı̄kh, 2: 790.

162 Al-Fasawı̄, Kitāb al-Maʿrifa wa al-tārı̄kh, 2: 783; al-Khat ̇ı̄b al-Baghdādı̄, Tārı̄kh

Baghdād, 13: 396–7.

Accusing Abu Hanifa of Being a Jew or Christian p. 214

Some went even further than this. A scandalous rumour was circulated in tenth-century Wāsit: someone had told someone else that he heard Ibn Abı̄ Shayba say that he suspected Abū Hanı̄fa was a Jew.22 Similar outlandish attempts to malign Hanafı̄s were originating, once more, from Wā sit.23 Shādhdh b. Yahyā al-Wā sitı̄ , a companion of Yazı̄d b. Hārūn, reports that he heard Yazı̄d say: ‘I have not seen anyone who resembled the Christians more than the followers of Abū Hanı̄fa.’24

Al-Khatı̄b al-Baghdā dı̄, Tārı̄kh Baghdād, 15: 566 (mā ra’ay tu qawm ashbah bi al-nasārā ̇ ̇min ashāb Abı̄ Hanı̄fa

Ibn Hanbal (d. 241/855): Abu Hanifa Went Against Sunnah p. 225-226

ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal rallied against Abū Hanı̄fa for supposedly permitting the consumption of pork, alcohol, and other prohibited drinks.84 He was aghast at Abū Hanı̄fa’s edict that breaking musical instruments was a punishable crime.85 Other proto-Sunni traditionalists claimed that Abū Hanı̄fa permitted adultery and usury and that his jurisprudence led to the shedding of blood with impunity.86 Many were, of course, puzzled and startled by these allegations. When a sceptic demanded an explanation, he was told that Abū Hanı̄fa permitted usury because he did not object to deferred credit transactions that accrue additional charges (nası̄’a); he permitted public violence (al-dimā’) since he ruled that if a man kills another man by striking him with a massive stone, the blood money must be paid by his male relatives, tribe, or social group (al-ʿāqila); he permitted adultery because he ruled that if a man and a woman have sexual intercourse in a house, whilst they are known to be parents, and both declare themselves that they are married to each other, no one should object to them. Upon hearing this detailed explanation the sceptic remarked that all of this amounted to invalidating God’s laws (al-sharā’iʿ) and injunctions (al-hkām).87

84: Abd Allā h b. Ahmad b. Hanbal, Kitāb al-Sunna, 206–7.

85: Abd Allā h b. Ahmad b. Hanbal, Kitāb al-Sunna, 206–7.

86: Al-Khatı̄b al-Baghdā dı̄, Tārı̄kh Baghdād, 15: 569.

87: Al-Khatı̄b al-Baghdā dı̄, Tārı̄kh Baghdād, 15: 569–70

Qiyas & Hadith p. 227

The analogical reasoning of Abū Hanı̄fa and his followers, however, was believed to bring about legal rulings that contradicted Prophetic reports. Ahmad b. Hanbal’s son ʿAbd Allāh would cite reports to the effect that Abū Hanı̄fa permitted eating pork, drinking alcohol, and forbade the breaking of musical instruments. 92 – p. 227

92 ʿAbd Allā h b. Ahmad b. Hanbal, Kitāb al-Sunna, 206–7

Abu Hanifa Weak in Hadith p. 229-230

Al-Tirmidhı̄ (d. 279/892) claimed that Abū Hanı̄fa had told his students as much: ‘Most of the hadı̄th I relate to you are mistaken (ʿāmmatu mā uhaddithukum khata’).’ 102 – p. 229

Al-Tirmidhı̄,ʿIlalal-Tirmidhı̄al-kabı̄r, arranged by Abū T ̇ālibal-Qād ̇ı̄ [Mahmūdb.ʿAlı̄ (d. 585/1189)], ed. Subhı̄ al-Sāmarrā’ı̄ , Abū al-Maʿātı̄ al-Nūrı̄ , and Mahmūd Muhammad Khalı̄ l al-Saı̄dı̄ (Beirut: ʿĀ lam al-Kutub/Maktabat al-Nahd ̇ a al-ʿArabiyya, 1989), 388. Al-Tirmidhı̄ wrote two works on this subject: al-ʿIlal al-kabı̄r (IK) and al-ʿIlal al-saghı̄r (IS). ̇

Muslim b. al-Hajjāj’s book on the subject of hadı̄th transmitters and their nicknames arrived at a similar conclusion: Abū Hanı̄fa was deficient in hadı̄th, and had very few sound hadı̄th.103 Al-Nasā’ı̄’s verdict was that Abū Hanı̄fa ̇ was weak in hadı̄th.104 In his short book describing the standards of individual hadı̄ th scholars, al-Jūzajānı̄ described Abū Hanı̄fa as someone whose hadı̄th could not be relied upon.105 In his Sunan, al- Dāraqut ̇nı̄ called Abū Hanı̄fa weak (daʿı̄f) in hadı̄th, and reportedly communicated the same point to Hamza al-Sahmı̄. Still, Abū Hanı̄fa found no place in al-Dāraqutnı̄’s history of weak hadı̄th scholars.106

103 Muslimb.al-H ̇ajjāj,Kitābal-Kunāwaal-asmā’,ed.ʿAbdal-Rah ̇ı̄mMuh ̇ammadAh ̇mad al-Qashqarı̄ (Medina: Ihyā ’ al-Turā th al-Islā miyya, 1984), 276.

104 Al-Nasā ’ı̄, Kitāb al-Duʿafā’ wa al-matrūkı̄n, 240 (laysa bi al-quwwa fı̄ al-hadı̄th).

105 Al-Jū zajā nı̄ , Ahwā l al-rijā l, 75

106 Al-Dāraqutnı̄ , Sunan, 2: 107–8, 1: 223, 323 (al-Arna’ūtedn.); al-Sahmı̄ , Su’ālāt Hamza b. Yūsuf al-Sahmı̄lial-Dāraqutnı̄, 263, where we are informed that Abū Hanı̄fa’s hadı̄th transmissions were unreliable since he never met a Companion.

al-Bajalı̄, al-ʿUqaylı̄ quotes the expertise of ʿAbd Allā h b. Ahmad b. Hanbal. When the latter was asked whether al-Bajalı̄ was a reliable hadı̄th scholar (sadūq), he replied: ‘No ̇ ̇ one should relate anything on the authority of Abū Hanı̄fa’s followers (ashāb Abı̄ Hanı̄fa).’ ̇ ̇ ̇ 117 – p.232

117 ̇ ̇Al-ʿUqaylı̄, Kitāb al-Duʿafā’, 1: 36–8 (Dār al-Sumayʿı̄ edn.).

Al-Jawraqānı̄’s (d. 543/1148) book on false and sound hadı̄ths twice cites hadı̄ths containing Abū Hanı̄fa in the isnāds. He declares them to be false and states that Abū Hanı̄fa’s hadı̄ths are to be renounced (matrūk al-hadı̄th).120 – p.232-233

Al-Jawraqānı̄, al-Abātı̄lwaal-manākı̄rwaal-sihāhwaal-mashāhı̄r, ed.ʿAbdal-Rahmān ̇ʿAbd al-Jabbā r al-Faryū wā ’ı̄ (Benares: Idā rat al-Buh ̇ ū th al-Islāmiyya wa al-Daʿwa wa al-Iftā ’, 1983), 2: 111, 170–1.)

Another critic explained, ‘It was not on account of Abū Hanı̄fa’s juristic reasoning that we loathed him; after all, we all resort to juristic reasoning. Rather, we loathed him because when a hadı̄th from the messenger of God was mentioned to him, he would give an opinion contrary to it.’124 Hammād b. Salama was thought to have made this very complaint, too: ‘When faced with traditions and practices (al-āthār wa al-sunan), Abū Hanı̄fa would counter them with his juristic reasoning.’125 – p. 232

Abd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal, Kitāb al-Sunna, 210

11th Century Opinion Attempt to Make Abu Hanifa Orthodox

We should recognise that this important phenomenon had an impact on hadı̄th masters of the eleventh century such as al-Hākim al-Nı̄shāpūrı̄, who included Abū Hanı̄fa as one of the hadı̄th scholars of Kufa.126 Al-Hākim even implies as much at the outset of the chapter when he writes: ‘This category concerns those famous, trustworthy, leading scholars from the generation of Successors and their successors whose hadı̄th were collected for the purposes of memorisation, learning, and to gain blessings through them.’127 For the great hadı̄th master al-Hākim, there was no doubt that Abū Hanı̄fa belonged to this category of hadı̄th specialists. This was nothing short of a sea change, then, from the days of ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal in the ninth century to al-Hākim in the eleventh. – p. 234

Al-Hākim al-Nı̄shā pūrı̄, Maʿrifat ʿulūm al-hadı̄th, 649 & 642 (Dār Ibn Hazm edn.)

Abu Hanifa Incurable Disease p. 250

ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal > Mutrif al-Yasārı̄ al-Asamm > Mālik b. Anas said: ‘The incurable disease is the destruction of faith. Abū Hanı̄fa is the incurable disease.’196 ̇

Ibn ʿAdı ̄ > Ibn Abı ̄ Dawud > al-Rabıʿ b. Sulayman al-Jızı > al-Harith b. Miskın > Ibn al-Qāsim > Mālik said: ‘The incurable disease is the destruction of faith, and Abū Hanı̄fa is [one manifestation] of the incurable disease.’197

196: ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal, Kitāb al-Sunna, 223.

197: Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil fı̄ al- ̇duʿafā’ al-rijāl, 8: 236–7 (ʿAbd al-Mawjū d edn.).

Abū Zurʿa tells us that Ayyū b al-Sakhtiyā nı̄ was once in Mecca – teaching a class, presumably–when Abū Hanı̄fa happened to enter the study-circle. Upon learning of Abū Hanı̄fa’s presence, Ayyūb brought an end to proceedings. ‘Stand up,’ he exclaimed to his students, ‘otherwise he will infect us with his disease.’216 – p. 225

216: Abū Zurʿā al-Dimashqı̄, Tārı̄kh, 2: 507. Ayyūb’s remark seems to invoke an Arabic proverb: ‘More contagious than the infection among the Arabs (aʿda min al-jarab ʿinda

al-ʿarab)’. See Lane, An Arabic–English Lexicon, 1.2: 403 (s.v. ‘jarab’). The editor of Abū Zurʿa’s history has it has yuʿdinā. I am reading the lā as the lām al-duʿā’ (or ‘lā of prohibition’, as Wright has it), which is why I place the verb in the jussive. Another alternative may be to replace the ʿayn with a hamza, which would give us yu’idnā (to infect us). See Wright, A Grammar of the Arabic Language, 2: 36.)

Abu Hanifa Ruling on Location of Kaaba & Identity of Muhammad p. 257

ʿAbd Allāh b. Ahmad b. Hanbal < Ahmad b. Hanbal < Mu’ammal b. Ismāʿı̄ l < Sufyān al-Thawrı̄ < ʿAbbād b. Kathı̄r said: ʿAmr b. ʿUbayd said to me: ‘Ask Abū Hanı̄fa about a man who says: I know that the Kaʿba is a reality and that it is the house of God, but I do not know if it is the house in Mecca or the house in Khurā sā n. Is such a person a believer?’‘ He is a believer,’ replied Abū Hanı̄fa. ʿAmr b. ʿUbayd then asked me to ask Abū Hanı̄fa about a man who says, ‘I know that Muhammad is a real person and that he is the messenger of God, but I do not know whether he is the person who lived in Medina or some other person.’ Is such a person a believer? ‘Yes, he is a believer,’ said Abū Hanı̄fa.

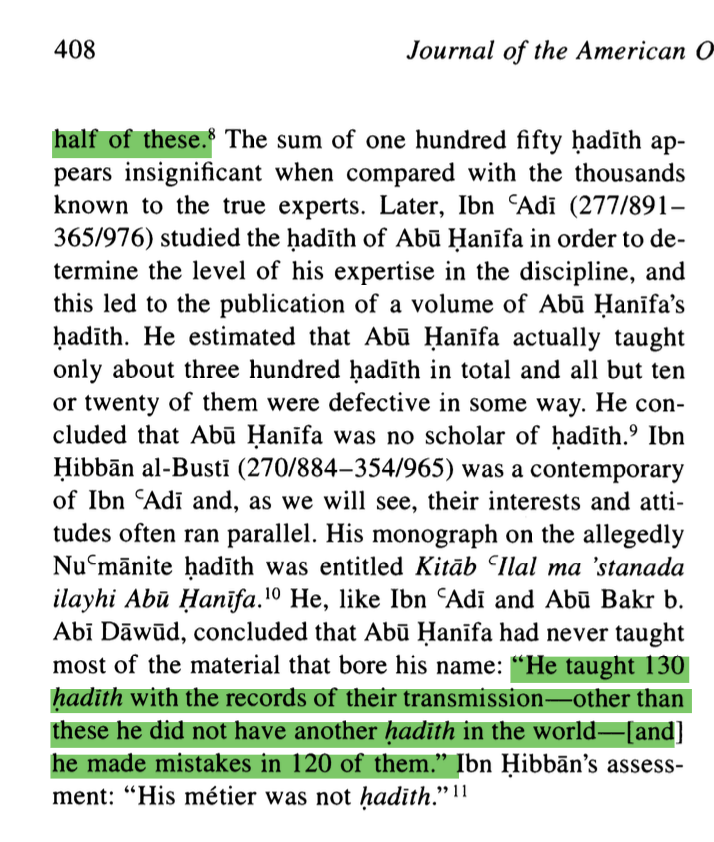

Ibn Hibban (d. 354/965) pp. 323-324

Ibn Hibbān tells us that Abū Hanıfa transmitted 130 hadıths with isnads. Ibn Hibban wrote with supreme confidence that there are no other hadı̄ths from him in the entire world other than these 130. Of these 130 hadı̄ths, Ibn Hibbān believed that Abū Hanı̄fa had committed errors in 120 by way of either mixing up the isnāds or changing the matn. He concludes that in situations when someone’s errors significantly outweigh their positive results, their traditions cannot be relied upon. This seems like a précis of Ibn Hibbān’s now lost book on the defects of Abū Hanı̄fa’s hadı̄ths. For Ibn Hibbān this was not the only reason for Abū Hanı̄fa to be denounced. He continues in the next sentence: ‘There is another reason why one cannot use him as a proof and that is because he invited people to [the heresy of] Irjā’, and there is a total consensus among every single one of our imams that one may not rely upon somebody as a proof if he calls others to heresy (al-bidaʿ).’66

66 Ibn Hibbān, Kitābal-Majrū ̇hı̄n, 2:405–6 (Riyadhedn.)

Every Reputable Scholar Denounced Abu Hanifa p. 334

Ibn ʿAdı̄ recalls the celebratory words of Sufyān al-Thawrı̄ when he learned of Abū Hanı̄fa’s passing: ‘Praise be to God. He was destroying Islam systematically. No one was born in Islam more harmful than him.’27 Abū Hanı̄fa is described as a devil who opposed the reports of the Prophet Muhammad with his ̇speculative jurisprudence.28 His hadı̄th learning is described in the most unflattering fashion.29 Finally, we have the claim that a group of ninth-century proto-Sunni traditionalists refused to accept the legal testimony of Abū Hanı̄fa and his followers.30 There is one passage, however, that provides an important insight into Ibn ʿAdı̄ ’s attempt to push back against the growing consensus of Abū Hanı̄fa’s orthodoxy by urgently reminding his audience of an older, well-established consensus among proto-Sunni traditionalists. He writes:31

There is a consensus of the scholars as to the fall of Abū Hanı̄fa. We know this because the leading authority of Basra, Ayyūb al-Sakhtiyānı̄ had aspersed him; the leading authority of Kufa, al-Thawrı̄ , had aspersed him; the leading authority of the Hijāz, Mālik, had aspersed him; the leading authority of Misr, al-Layth b. Saʿd, had aspersed him; the leading authority of Shām, al-Awzāı̄ , had aspersed him; and the leading authority of Khurāsān, ʿAbd Allāh ̇ b. al-Mubārak, had aspersed him. That is to say, we have here the consensus of the scholars in all of the regions.

In another place, Ibn ʿAdı̄ expresses the very same sentiment: ‘There is not a scholar who is well respected except that he has denounced Abū Hanı̄fa.’32

25: Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 239 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 125).

26: Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 239 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 125).

27: Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 239 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 126).

28: Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 239 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 125).

29: Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 236 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 121 (lā yuktab hadı̄thuhu, mudtarib al-hadı̄th, wāhı̄ al-hadı̄th), 237 = 122-3 (fı̄ al-hadı̄th yatı̄m, laysa sāhib al- ̇hadı̄th, laysa bi al-qawı̄), 238 = 123 (matrūk al- ̇hadı̄th).

30: Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 239 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 124–5).

31: Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 241 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 129) (samiʿtu Ibn Abı̄ b. Dāwūd yaqūl: al-waqı̄ʿa fı̄ Abı̄ Hanı̄fa, ijmāʿuhu min al-ʿulamā’ li anna imām al-Basra Ayyūb al-Sakhtiyānı̄ wa qad takallama fı̄hi; wa imām al-Kūfa al-Thawrı̄ wa qad takallama fı̄hi; wa imām al-Hijāz Mālik wa qad takallama fı̄hi; wa imām Misr al-Layth b. Saʿd wa qad takallama fı̄hi; wa imām al-Shām al-Awzāʿı̄ wa qad takallama fı̄hi; wa imām Khurāsān ʿAbd Allāh b. al-Mubārak wa qad takallama fı̄hi. Ijmāʿ min al-ʿulamā’ fı̄ jamı̄ʿ al-āfāq aw kamā qā la).

32: Ibn ʿAdı̄, al-Kāmil, 8: 238 (Dār al-Kutub edn. = Riyadh edn., 10: 123) (lam yakun bayn al-mashriq wa al-maghrib faqı̄han yudhkar bi khayr illā ʿāba Abā Hanı̄fa wa majlisahu).

A fascinating parallel can be found in the work of Ibn Hibbān. In the notice on Abū Hanı̄fa in Kitābal-Majrūhı̄n, Ibn Hibbān writes:

Among every single one of our imams, I know of no disagreement between them concerning him [Abū Hanı̄fa]: the leaders of the Muslims and those of scrupulous piety in the religion, in all of the regions and provinces [of the Islamic world], one after another, they all have declared him to be unreliable and have vilified him. We have included examples of these statements in our book entitled ‘The Warning about the Falsification’. There is no need, then, to repeat all of this in our present book. Instead, I shall simply cite here a summary from which readers will be able to deduce for themselves everything else that lies behind it. – p. 335

Ibn Hibbān, Kitāb al-Majrūhı̄n, 3: 64 (Beirut edn.) = 2: 406 (Riyadh edn.))

Did Abu Hanifa Write Any Books? p. 349

The question of whether Abū Hanı̄fa actually composed any works is not a simple one; eighth- and ninth-century authors did not remember him as an author. His detractors did not cite specific books or passages in the course of their diatribes against him. His students, followers, and admirers neither cited nor pointed to his books to defend him against his critics until the eleventh century.1 In line with one of the finest researchers and philologists of Islamicate learning, Murtadā al-Zabı̄dı̄, where medieval sources do refer to kutub Abı̄ Hanı̄fa, one possibility is that the authors intended notebooks or dictation to his students.

2 thoughts on “Notes & Quotes: Abu Hanifa, Hadith, & Sunni Heresy”