Hafs an Asim, was not common in the Arab and Muslim world until the Ottomans adopted it as the official Reading of the Empire. Furthermore, the first complete audio recording of the Quran was done by Mahmud Khalıl al-Hus ̇arıin 1961, and it followed the Reading of Hafs an Asim, which became the dominant Reading in the Arab and Muslim world, whereas all the other canonical Readings started to die out except among specialists and highly educated scholars. p.1

Many prominent Muslim scholars such as al-Tabarı (d.310/923), who wrote a book on twenty variant Readings of the Quran attributed to twenty eponymous Readers, and al-Zamakhshar ̄ı (d. 538/1144), rejected several canonical readings and gave preference to some readings over others; they did not adopt one complete system by an eponymous Reader but chose from the different readings circulating at the time the reading that best suited their interpretation of the verse p. 6-7

Muhammad Habash counted forty-nine scribal differences among the Uthmanic codices, deduced from the differences among the canonical Readings that inevitably had to result from the consonantal differences in the rasm, such as additions or omissions of prepositions and conjunction particles. p.6

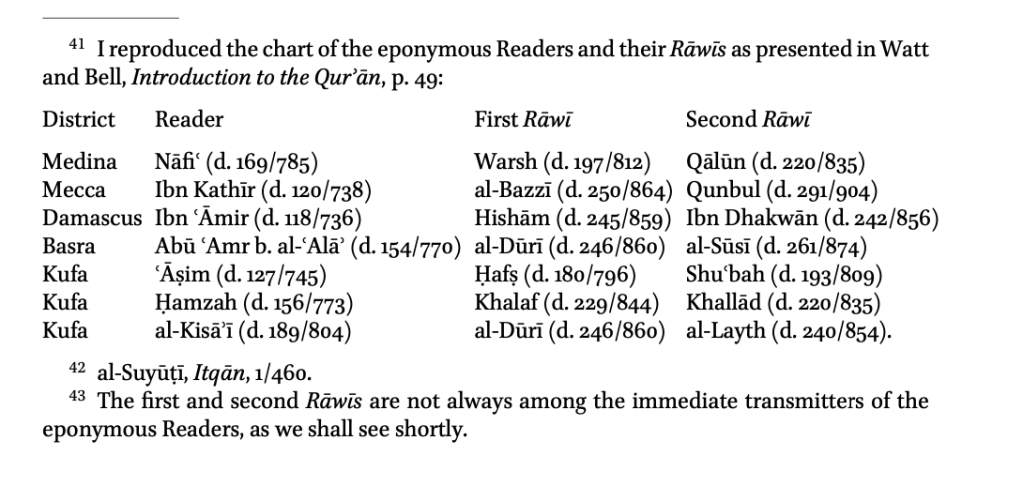

Despite Uthman’s efforts to codify the text of the Quran and limit its variants, the different readings of the Qunanic text, permitted by the nature of the defective rasm, kept multiplying with time until Ibn Mujahid (d. 324/936) limited them under seven eponymous Readings. p10

al-Suyutı enumerates thirty-five different interpretations of the sabat ahruf tradition, ranging from linguistic to esoteric interpretations. Muslim scholars, however, unanimously agree that the sabat ahruf are not al-Qiraat al-Sab’, which were collected and canonized by Ibn Mujahid (d. 324/936). According to them, only the ignorant masses took the sabat ahruf of the Prophetic tradition to be the seven canonical Readings. p.15

It is worth mentioning that the shias nowadays read the Quran according to the Reading of Asim in the recension of his student Hafs (Haf ̇s an Asim, Hafs → Asim). This is probably justified by the fact that the isnad of this canonical Reading goes back to Ali b. Abi Talib. p33

In the late 8th/14th century, Ibn al-Jazar ̄ı (d. 833/1429) became the leading authority in the field of Qiraat. He canonized three additional Readings and requested an official fatwa ̄ from Ibn al-Subkı (d. 771/1370) to proclaim the tawatur of the ten canonical Readings. p. 36

Ever since Ibn al-Jazarı and al-Suyutı (d. 911/1505), the tawa ̄tur of the Quran and its variant canonical Readings have become self-evident truths not open to discussion and questioning.

This consensus comprises also the fact that no one could recite and teach the “obsolete” readings of the Companions, which disagree with the consonantal outline of the Uthmanic codices. Those who opposed Ibn Mujahid’s officially promulgated “Canon” and insisted on following their own standards and criteria were tried, flogged, and coerced into adhering to the consensus. p. 36

The most important and influential among the scholars who collected different Qiraat before Ibn Mujahid was presumably al-Tabar ̄ı, who was one book, now lost, in which he collected more than twenty variant Readings of the Quran. We do not know much about this book, however, it is very probable that al-Tabari did not intend to canonize the different readings of the Quran, which were in wide circulation at the time. He also did not intend to exclude the readings which were invalid according to his own standards. AsonecanseefromhisTafsır, al-Tabari often lists most of the readings of the verse known to him followed by his own judgment and ijtihad where he favors one reading over another. p.39

Several Muslim religious authorities have written treatises criticizing al-Tabari and his position on the canonical readings, some of which he considered to be erroneous and invalid. Labıb al-Saıd, for example, in his Difa’an al-Qiraat al-Mutawatirah fı Muwajahat al-Tabarı al-Mufassir, collected eighty-nine examples from al-Tabarı’s Tafsır, in which the latter refused many canonical readings and gave preference to some readings over others. p.40

Ahmad b. Hanbal (d.241/855) was known for loathing some aspects of Hamzah’s Reading, while Abu Bakr Shubah (d.193/809), Asim’s canonical Raw ̄ı, stated that Hamzah’s Reading was an innovation (bidah). Many notable scholars would consider the prayer to be invalid if the Quran were criticized Hamzah and even belittled him. Once more, we encounter a ̇ recited according to Hamzah’s Reading. It was also said that Hamzah was not skilled in Arabic and that he used to make a lot of grammatical mistakes. p.58

Had Ibn Mujahid or the seven eponymous Readers themselves believed that the variant readings were of divine nature, they would not have tried to argue for or against certain readings. p. 60

Ibn Mujahid’s decision to limit the canonical Readings to Seven has caused unrest among Muslim scholars since the 4th/10th century. No one was certain of Ibn Mujahid’s intentions; did he intend, at least subconsciously, to realize the number Seven for his selected Readings and therefore, retroactively vindicate, or simply honor, the Prophetic tradition of the sab’at ahruf? Ibn al-Jazarı clearly states that Ibn Mujahid’s true intention was to make the seven Readings correspond to the sab’at ahruf and Uthman’s seven codices. On the other hand, he is certain that Ibn Mujahid could not have believed or even considered the possibility of the seven ahruf to “be” the seven Readings, as many people have assumed later on. p.63

According to Ibn Salah and al-Nawawi, a mutawatir report is one which yields necessary knowledge as a result of the ̇sidq (honesty/truthfulness) of its transmitters; this should be true throughout all the generations and classes of transmitters. The question that must be asked here is why the Hadıth theoreticians avoided the expression “a sufficient number of people”. The answer might lie in the fact that the maximum number of first-generation transmitters any hadith could tolerate is sixty-two Companions. The standard usuli definition which entails a sufficient or large number of people (al-jam’/al-jamm al-ghafır) does not apply to any of the Prophetic traditions, even the most authentic and sound hadıth among them. p.72-73

Early Muslim scholars did not look at the variant readings of the Quran as divine revelation. They attributed the Quranic variants to human origins, either to the reader’s ijtihad ̄d in interpreting the consonantal outline of the Quran or simply to an error in transmission. This position changed drastically in the later periods, especially after the 5th/11th century where the canonical Readings started to be treated as divine revelation, i.e. every single variant reading in the seven and ten eponymous Readings was revealed by God to Muhammad. p.77

Al-Ghazāl presumes that al-Shāfī was inclined to believe that the basmalah is a verse in every single sūrah of the Quran, including (Q.1): al-fatihah/al-hamd. However, he wonders if al-Sha ̄fi’ı believed that the basmalah is an independent verse by itself in each su ̄rah or if it is part of the opening verse of each chapter. p.89

al-Ghaza ̄l ̄ı’s opponents complicate the question further and ask: since Muslim scholars have disagreed on the Quranic nature of the basmalah, this implies that tawatur does not necessarily yield indisputable and absolute knowledge. p.89

Moreover, many accounts state that the Prophet did not use to know the beginning or the end of the su ̄rah unless the basmalah would be revealed. Hence, it is presumptuous to suggest that what was revealed alongside the Quran with the beginning and end of each su ̄rah is not Quranic. On top of that, many accounts at test that several Companions openly declared that the basmalah is an opening Qurnanic verse in each surah, yet they were never contested or deemed to be wrong. Had the basmalah not been Quranic, other Companions would have objected to those Companions’ declaration of the Quranity of the basmalah. Additionally, Ibn Abbas stated in an authentic and sound account that Satan (al-Shay ̇ta ̄n) stole a verse from the Quran, namely al-basmalah, which implies that many Muslims had stopped reading it in the openings of the surahs. p. 91

al-Ba ̄qilla ̄n ̄ı responds to the above arguments in detail. He argues that it is not certain whether the basmalah is only an opening verse in al-fa ̄tihah or an opening verse in every surah; however, he is inclined to believe that it is not a verse in the Quran at all except in su ̄rat al-naml (Q.27:30).There are several sound accounts confirming that the Prophet, the Caliphs and the scholars (ima ̄ms) did not recite the basmalah audibly at the beginning of al-fatihah. Had the basmalah been part of al-fatihah, it would have been absurd to recite some parts of it audibly while reciting the other parts inaudible. This proves that the basmalah is not part of al-fatihah and that it is only a verbal device to start the su ̄rah. p.92

Moreover, al- Ba ̄qilla ̄n ̄ı admitted that the basmalah was written down in the Quran at the beginning of each surah with the same script as the rest of the Quran unlike the titles of the surahs, which we rewritten in a different script in order to clarify their non-Quranic nature. p.93

al-Ghazali says that incorporating any non-Quranic materials, be it the basmalah or anything else, into the Quran is known to be an act of infidelity (kufr). p.93

Since the basmalah was written down in the mu ̇s ̇haf in the same script as the rest of the Quran, and since it was revealed to the Prophet at the beginning of each su ̄rah, it is unimaginable to presume that the Prophet would allow the Muslims to be confused regarding its nature and not publicly declare its non-Quranity. Therefore, the Prophet’s silence on the nature of the basmalah suggests that it is Quranic. p.94

The Malikis did not trouble themselves with this notion of ijtiha ̄d because they absolutely denied the basmalah’s Quranic nature except in (Q. 27:30). p.95

According to the Ma ̄lik ̄ıs, the basmalah is not a Qur’an “a ̄nic verse at all except for (Q.27:30). The Hanaf ̄ıs believe that the basmalah is a Quranic verse by itself; nevertheless, it is not part of al-fatihah or any other surah; it is rather an independent verse revealed to separate the su ̄rahs from each other; p. 95

Another problematic issue that the u ̇su ̄l ̄ıs had to deal with during their discussion of the Quran as a source of law is Ibn Masud’s famous anomalous reading of (Q.5:89)“…fa- ̇siya ̄muthala ̄thatiayya ̄minmutata ̄bia ̄tin” (…then three successive days of fasting). This reading resulted in the legal problem “al-tata ̄buf ̄ı ̇sawmkaffa ̄ratal-yam ̄ın” (fasting three consecutive days to expiate breaking the oath). Muslim Scholars have dismissed the anomalous reading of Ibn Masud and deemed it to be sha ̄dhdhah because it was not transmitted through tawatur. Despite the fact that the Hanafıs required succession in fasting the three days based on Ibn Masud’s reading, they have also considered the reading to be sha ̄dhdhah and treated it as a tradition only (khabar). p. 96

Muslim scholars have disagreed whether the basmalah is an opening Quranic verse in every su ̄rah or not. Those who believe that it is Quranic base their argument on the fact that the basmalah is written down in the ma ̇sa ̄ ̇hifatthebeginningofeverysu ̄rahwiththesamescriptastherestof the Quran, unlike the titles of the su ̄rahs, which were written with a different script to indicate their non-Quranic nature. These scholars also refer to several traditions that suggest the Quranity of the basmalah in every surah. On the other hand, other scholars believe that the basmalah is not a Quranic verse in every su ̄rah, despite the fact that it was written down in the ma ̇sa ̄ ̇hif, simply because tawa ̄tur was not established as far as the Quranity of the basmalah is concerned. The simple fact that there is already a disagreement among Muslim scholars on the Quranity of the basmalah is sufficient to exclude it from the Quran, which should be absolute; no part of the Quran, however small, might be accepted through ahad transmission, and thus, become subject to doubt. Tawatur, which is equivalent here to the consensus of the ummah or the scholars, supersedes the fact that the basmalah was written down in the mushaf. Since there is no consensus on the nature of the basmalah, it failed to establish tawatur, and thus, was deemed to be ahad. Even those who assumed its Quranic nature never claimed that it was transmitted through tawatur. p.97

The following points summarize the main arguments of the previous two sections:

- According to some u ̇sulıs, tawatur is considered to be a parameter in the definition (hadd) of the Quran and a characteristic of its nature.

- Other usulıs refuse to consider tawatur as a parameter in defining the Quran yet still stipulate tawatur as an essential condition to validate and authenticate the Quran.

- Almost all u ̇su ̄l ̄ıs agree that the Quran cannot be authenticated through ahad transmission. Each single verse must be authenticated through tawatur in order to acquire gain the Quranic status.

- Even though the basmalah was written down in the ma ̇sa ̄ ̇hif with the same script as the rest of the Qur’a ̄n, its transmission did not amount to the status of tawatur. Scholars have disagreed on its Quranic nature; is it an opening verse in every surah, or an opening verse in al-fa ̄tihah

- alone, or not a Quranic verse at all?

- Ibn Masud’s reading of (Q.5:89) was not transmitted through tawatur.

- The reading did not establish a mandatory legal ruling for the Sha ̄fi ̄ıs and the Malikıs because it lacked the condition of tawa ̄tur and consequently lost its Quranity. Nevertheless, the H ̇anafıs stated that the reading should establish a legal ruling by regarding this anomalous reading as a tradition (khabar), which necessitates action but not knowledge. p.97-98

Ibn al-Arabı makes an audacious statement seldom adopted by other Muslim scholars; he says that few inconsistencies occurred during the process of copying the ma ̇sa ̄ ̇hif, the process which was undertaken by Zayd b. Tha ̄bit and his committee. These inconsistencies comprised four or five letters; however, they increased when the Quran readers further disagreed among each other on some forty letters, among which are the waw, ya, and alif. There were no inconsistencies in full words except in two places in the Qur’an, both of which are two-consonant words; the first is “huwa” (he) in (Q. 57:24), and the second is “min” (from) in (Q. 9:100). p.105

The common Reading that the Sh ̄ıah use is Asim←Hafs; which is conveniently suited for their theological doctrine, since Asim’s isnad of his Reading ends up with Alı b. Abı Talib. p. 115

A simple example of farsh would be Asim and al-Kisaı’s readings of (Q.1:4) mlk as malik while the rest of the Readers read “malik”. Ibn Kathır, Nafi, Abu Amr b. al-Ala’ read krh as “karhan” in (Q.4:19) and (Q.46:15), where as Hamzah and al-Kisaı read “kurhan” in both verses. Asim and Ibn Amir read “karhan” in (Q.4:19) but “kurhan” in (Q. 46:15). p. 122

Obviously, tawatur cannot be established among the Companions since those who memorized the whole Quran during the Prophet’s lifetime and shortly after his death were handful, possibly four Companions only. p.129

One can immediately notice that the number of the immediate transmitters of the eponymous Readers dropped substantially between Ibn Mujahid and Ibn Ghalbun. The seventeen immediate transmitters of Nafi dropped to four only, where as Asim’s immediate transmitters dropped from twelve to three, and the immediate transmitters of Abu Amr b. al-Ala’ dropped from ten to one and only one. One can deduce from the considerable decline in the number of the immediate transmitters that there was an essential need to limit the number of transmitters and subsequently their transmissions of variants. p.133

How could a transmission through one or three or ten or even seventeen transmitters be characterized as mutawa ̄tir? We are able now to realize how problematic the subject of tawatur al-Qiraat was, and why many scholars admitted bitterly that the canonical Readings were transmitted through single (ahad) chains of transmission and not through tawatur. p. 134

There search done by Juynboll on isnad analysis in Hadıth showed that a number of transmitters and common links invented several of their authorities in order to soundly connect their transmissions to the Prophet with a good isna ̄d, which Juynboll called a “diving isnad”. Diving isnad bypasses a transmitter in order to aim directly at early transmitters so that a direct link might be established to the main source of transmission, i.e. the Prophet or the Companions. Juynboll also argued that many Companions’ names were invented in the transmission chains to establish more credibility in the isnad; Gautier H.A. Juynboll, “The Role of Muammaru ̄n in the Early Development of Isnad”

One thought on “Notes: The Transmission of the Variant Readings of the Quran (Shady Nasser)”