In the study of Hadith, biographies known as “Ilm al-Rijal” (the science of narrators) are considered crucial for assessing the reliability and credibility of Hadith transmitters. These biographies provide detailed information about the lives, characters, and trustworthiness of the individuals in the chains of narration (isnads).

Today, these biographical dictionaries are used to confirm a Hadith’s authenticity by assessing the reliability of each narrator in the chain. Scholars classify narrators into categories such as trustworthy (thiqa), weak (da’if), and unknown (majhul) based on the information provided in these works. The biographies aim to provide historical context and insights into narrators’ lives and conditions and are foundational for Hadith Sciences.

Most people today assume that the biographies came before the most notable collection of Hadith with their respective gradings, except, as we will see, this was not the case. Historically, the Hadith compilations were first produced, and then later, the biographies were created to justify the claims of the Hadith compilers. Or, put another way, the biographical information came after the compilation of the Hadith and was derived from the Hadith.

LIST OF PROMINENT BIOGRAPHIES

We can understand this by evaluating the dates of the different biographies, starting with the earliest compilations.

“Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir” by Ibn Sa’d

- Author: Muhammad ibn Sa’d ibn Mani’ al-Basri, commonly known as Ibn Sa’d or Ibn Sa’d al-Baghdadi.

- Date Completed: ~845 CE / 230 AH

- # of Biographies: thousands

- Content: “Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir” is one of, if not the earliest, biographical dictionary in Islamic literature we have. The book provides biographies of the Prophet Muhammad, his companions (Sahabah), and the subsequent generations of scholars and narrators (Tabi’in and Tabi’ al-Tabi’in).

“Tarikh al-Kabir” by Imam al-Bukhari

- Author: Muhammad ibn Ismail al-Bukhari (d. 870)

- Date Completed: ~866 CE / 252 AH

- # of Biographies: Originally ~12,300 men (no women), later updated (most likely by others) to include <40,000 biographies of both men and women.

- Content: This biographical dictionary focuses on Hadith narrators and mostly details regarding where each narrator resided.

“Al-Jarh wa al-Ta’dil” by Ibn Abi Hatim al-Razi

- Author: Ibn abi Hatim al-Razi

- Date Completed: ~938 CE / 327 AH

- # of Biographies: ~9,000

- Content: This work systematically categorizes narrators into levels of reliability and provides critiques from various scholars.

“Al-Kamil fi Du’afa’ al-Rijal” by Ibn Adi

- Author: Ibn Adi

- Date Completed: ~976 CE / 365 AH

- # of Biographies: ~4,000

- Content: This work focuses on weak narrators, providing detailed critiques and the reasons why they are considered unreliable.

“Mizan al-I’tidal” by Al-Dhahabi

- Author: Al-Dhahabi

- Date Completed: ~1347 CE / 748 AH

- # of Biographies: ~11,000

- Content: This biographical dictionary includes both reliable and unreliable narrators, offering critical evaluations and justifications for their classifications.

“Siyar A’lam al-Nubala” by Al-Dhahabi

- Author: Al-Dhahabi

- Date Completed: ~1351 CE / 751 AH

- # of Biographies: ~6,000

- Content: This is a biographical encyclopedia covering prominent figures in Islamic history, including Hadith narrators.

“Lisan al-Mizan” by Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani

- Author: Ibn Hajar Al-Asqalani (d. 852 AH)

- Date Completed: ~1426 CE / 830 AH

- # of Biographies: ~5,600

- Content: A supplement and expansion of Al-Dhahabi’s “Mizan al-I’tidal,” it includes additional narrators and further details.

“Tahdhib al-Tahdhib” by Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani

- Author: Ibn Hajar Al-Asqalani (d. 852 AH)

- Date Completed: ~1428 CE / 831 AH

- # of Biographies: ~12,000

- Content: This is a biographical dictionary that summarizes the evaluations of earlier scholars regarding the narrators of Hadith.

“Taqrib al-Tahdhib” by Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani

- Author: Ibn Hajar Al-Asqalani (d. 852 AH)

- Date Completed: ~1439 CE / 841 AH

- # of Biographies: ~8,000

- Content: A condensed version of “Tahdhib al-Tahdhib,” providing brief evaluations and classifications of narrators.

BIOGRAPHIES CAME AFTER THE HADITH COMPILATIONS

When we contrast the books of biographies against the six canonical compilations of Hadith (Kitab al-Sittah), we see that all of these biographies, except “Kitab al-Tabaqat al-Kabir” by Ibn Saad, came after the compilations. As we will see later, even Bukhari’s Tarikh al-Kabir was not created or used prior to his Sahih compilation.

- Sahih al-Bukhari:

- Author: Muhammad ibn Ismail al-Bukhari (d. 870 CE / 256 AH)

- # of Hadith: ~7,275

- Grading: Sahih

- Sahih Muslim:

- Author: Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj (d. 875 CE / 261 AH)

- # of Hadith: ~7,500

- Grading: Sahih

- Sunan Abu Dawood:

- Author: Abu Dawood (d. 888 CE / 275 AH)

- # of Hadith: 5,274 hadiths

- Grading: Sahih, Hasan, Da’if

- Sunan at-Tirmidhi:

- Author: Muhammad ibn Isa at-Tirmidhi (d. 892 CE / 279 AH)

- Content: This collection includes hadiths and explanations of their authenticity. It contains around 4,400 hadiths.

- Sunan an-Nasa’i:

- Author: Ahmad ibn Shu’ayb an-Nasa’i (d. 915 CE / 303 AH)

- # of Hadith: ~5,800

- Grading: Sahih, Hasan, Da’if

- Sunan Ibn Majah:

- Author: Muhammad ibn Yazid ibn Majah (d. 887 CE / 273 AH)

- # of Hadith: ~4,341

- Grading: Sahih, Hasan, Da’if

CREDIBILITY OF NARRATORS

In Hadith studies, narrators are critically assessed based on several criteria to determine their reliability and trustworthiness. Here are the primary criteria used by Hadith scholars:

1. Adalah (Integrity)

- Definition: The narrator must be morally upright, demonstrating strong adherence to Islamic principles and ethics.

- Assessment: Scholars look at the narrator’s character, including their honesty, piety, and avoidance of major sins. Any known instances of lying or unethical behavior would disqualify a narrator.

2. Dhabt (Accuracy)

- Definition: The narrator must have a strong memory and precise retention of Hadith.

- Assessment: This includes the ability to accurately recall and transmit Hadith without mistakes. Scholars also consider whether the narrator took written notes and how meticulous they were in preserving and conveying Hadith.

3. Consistency

- Definition: The narrations of a particular Hadith by a narrator must be consistent and free from contradictions.

- Assessment: Scholars compare different transmissions of the same Hadith by the narrator to ensure consistency. Inconsistencies or contradictions can affect the reliability of the Hadith.

4. Conformity with Other Reliable Narrators

- Definition: The narrations should conform to what is known from other reliable sources.

- Assessment: A Hadith is cross-checked with other narrations from reliable narrators to ensure there is no significant deviation.

5. Reputation among Scholars

- Definition: The opinions of other recognized scholars about the narrator’s reliability.

- Assessment: Scholars such as Al-Bukhari, Muslim, Al-Dhahabi, and Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani have documented their assessments of various narrators. A positive consensus about a narrator’s reliability strengthens their credibility.

The irony is that the Hadith compilers and the biographers make these determinations post facto, hundreds of years after the narrator’s death. While the Hadith compilers had to do this based on their Hadith selections, later biographers would use the Hadith compiler’s selection and the content of the Hadith to try to retroactively confirm what the Hadith compilers provided them. Additionally, these individuals didn’t have a database to compare the hundreds of thousands of reports they supposedly scoured to determine errors. Instead, realistically, they had to do this by memory and intuition.

AGE OF NARRATORS

A significant tool in determining the authenticity of the isnad is knowing the birth and death of an individual in the chain of transmitters. This information will indicate that the two people in the chain of transmitters, at a minimum, lived in the same time period. If they did not, then the best case is that the Hadith has a broken chain, and the worst case is that it is a fabrication. But if this determination is being extrapolated by the isnad itself, then that becomes problematic because there is no neutral source by which to gauge the authenticity of this claim.

Because the ages of the narrators are generally inferred from the isnad, their ages are highly speculative. This is why there are often wide estimates of what year someone was born and how old they were when they died. Even for the most notable figures of Hadith, this information is uncertain. This is not limited to even relatively unknown transmitters. There is much uncertainty regarding the exact dates of birth and death of many of the most prominent individuals, including the prophet’s wife ‘Aisha, the Hadith scholar Ibn Shihab az-Zuhri, Anas ibn Malik, the companions Abu Bakr and Umar, and even the prophet himself. If the history is unclear for such notable individuals, how less reliable should we consider it for the multitude of individuals listed in the isnad?

Additionally, the isnad does not provide the year and age of the narrator when they narrated the report. In Hadith sciences, the age requirement for reliable transmitters of Hadith is that they should have reached the age of maturity and intellectual competence. This typically means they should be mentally mature and capable of understanding and accurately transmitting the Hadith. The exact age at which one is considered mature can vary in different contexts and among scholars, but it generally aligns with the age at which a person is considered an adult in their society. However, a common practice was to include the names of children deemed to be five years or older in the books as authorized recipients of traditions.

Aside from the ridiculousness of such practices, as stated in the excerpt above, this poses a more practical problem. It is one thing to know that the transmitter is only five years old. It is another when it is unclear if the transmitter was a child or an adult when they originally heard the Hadith. It is very likely that someone might have heard the Hadith when they were a child and not of sound mind, but later on, be taught the Hadith at an older age, but make their isnad to remove that intermediary.

For example, ‘Abd al-Razzaq was an eighth-century Yemeni hadith scholar who compiled a hadith collection known as the Musannaf of Abd al-Razzaq, and when he died in 211 AH at the age of 80, his student, Ishaq ibn Ibrahim al-Dabari, who transmitted his work was not more than 7 years old.6

Despite this being stated by the Khatib, Kifayah, p. 64 and Studies in Hadith Methodology and Literature p. 23, others claim that it was al-Dabari’s father who transmitted it to his son at an older age and that al-Dabari omitted his name from the transmission and only put his own which would reduce the length of the isnad.

Another common practice was that of “ijaza” (permission for transmission). According to p. 45 of “Hadith Muhammad’s Legacy in the Medieval and Modern World” by Jonathan A.C. Brown:

Ijaza for transmission meant that instead of reading an entire hadith collection in the presence of an authorized transmitter, a student might only read part of it and receive ‘permission’ from the teacher to transmit the rest. Although it was a less rigorous form of authentication, ijaza still provided scholars with isnads for books. Although this practice existed in some forms even in the ninth century, by the mid 1000s it had become very common. Al-Hakim al-Nayasburi, author of the massive Mustadrak, thus gave a group of students an ijaza to transmit his works provided they could secure well-written copies of them.

Of course if you could get an ijaza for a book you had not actually read in the presence of a teacher, you could get ijazas for any number of books that the teacher was able to transmit. This led to the practice of acquiring a ‘general ijaza (ijaza ‘amma)’ for all the books a teacher had. In the 1000s many scholars also accepted the practice of getting ijazas from teachers one had not actually met at all through writing letters. This ijaza for the non-present person (ijaza al-ma’dum)’ meant that scholars could acquire ijazas for their infant children or even for children not yet born!

BUKHARI EXAMPLE

Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī ( صَحِيحُ الْبُخَارِي) is the first hadith collection of the Six Books of Sunni Islam and is considered the most authentic of all the Hadith compilations. It was compiled by Persian scholar al-Bukhari (810-870 CE / 194-256 AH).

Some sources claim that Bukhari wrote his Tarikh al-Kabir after his Sahih, but this does not match the dates associated with each publication. Historically, “Sahih al-Bukhari” was compiled over a period of 16 years, starting from around 831 CE / 216 AH when Imam al-Bukhari was approximately 22 years old. Therefore, Sahih al-Bukhari was completed around 846 CE / 231 AH. Then, roughly twenty years later, around the year 866 CE / 252 AH, he completed his “Tarikh al-Kabir,” which contained his biographies.

Further proof that Bukhari completed his Tarik after his Sahih is that nowhere in his Sahih does he reference the work of Tarikh al-Kabir, yet there are potential references to his Sahih in his Tarik. On page 21 of the book by Muntasir Zaman entitled “The Textual Integrity of Sahih al-Bukhari,” he states:

In al-Tarik al-kabir, al-Bukhari directs readers to his book “al-Musnad” and another book titled “al-Mukhtasar.” Both labels are found in what later became the standard title of the Sahih (al-Jami’ al-musnad al-Sahih al-mukhtasar).

Zaman does point out some holes in the above claim, but realistically, it comes down to the dates of completion. According to most sources, Bukhari completed his Sahih in 846 CE / 231 AH, and according to the scholar Christopher Melchert in his article,”Bukhārī and Early Hadith Criticism,” he states that Bukhari wrote his Tarik in 866 CE / 252 AH.

Page 19 of Muntasir Zaman’s book “The Textual Integrity of Sahih al-Bukhari” indicates that al-Tarikh al-Kabir was written in 860 CE / 246 AH. In his footnote, he writes:

“38. In the opening paragraph of his recension of al-Tarikh al-kabir, Ibn Sahl al-Muqri’ states, “Abu ‘Abd Allah Muhammad b. Isma’il b. Ibrahim al-Ju’fi narrated to us in Basra in 246 AH.” See al-Bukhari, al-Tarikh al-kabir, 1:3.

According to the book “The Canonization of al-Bukhārī and Muslim” by Johnathan Brown, he states on p. 68:

“He [Bukhari] began his al-Tarikh al-kabir (The Great History) while a young man in Medina. The extant work is a massive biographical dictionary of over 12,300 entries. He is reported to have revised it at least three times over the course of his life, as Christopher Melchert corroborates in his analysis of the Tarikh. Al-Bukhri consistently provides neither full names nor evaluations of the persons in question, focusing instead on locating each subject within the vast network of hadith transmission. The Tarikh seems to have no connection to the Sahih.”

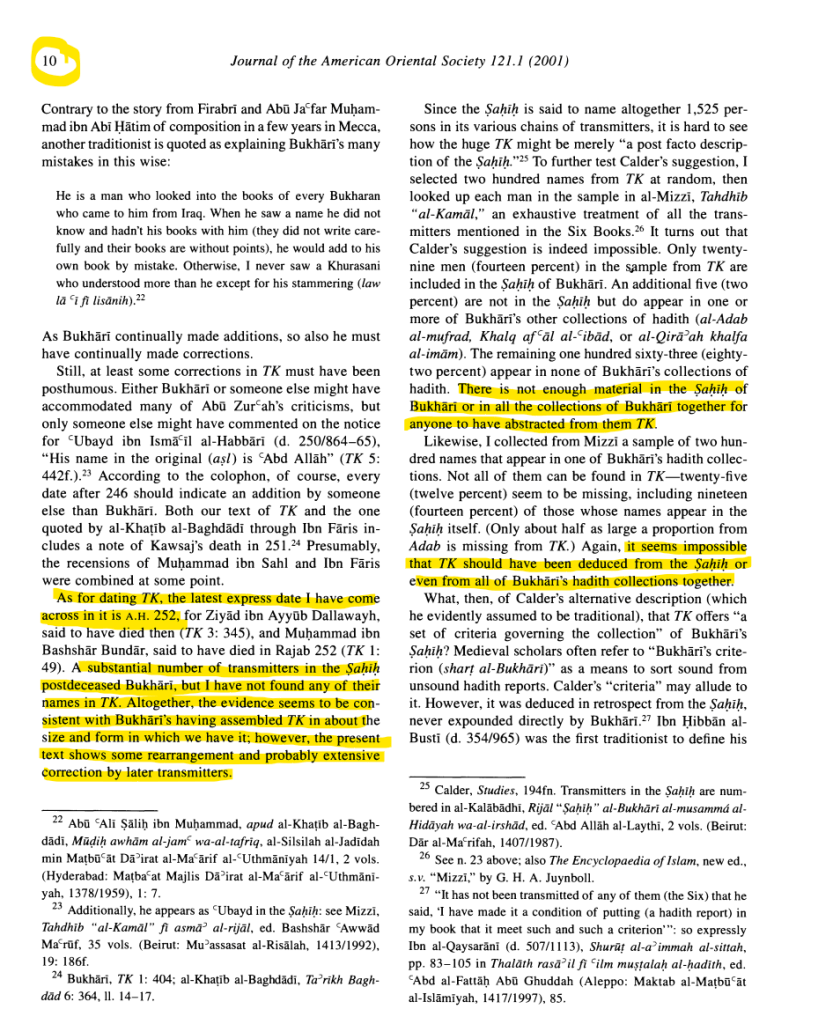

According to Christopher Melchert’s article, “Bukhārī and Early Hadith Criticism” it states:

Norman Calder has questioned the arrtibution of al-Tarikh al-kabir to al-Bukhari (d.256/870). Quotations from Ibn Hatim al-Razi and al-Khatib al-Baghdadi, together with comparisons among the rijal works of Bukhari, suggest that al-Tarikh al-kabir was one of Bukhari’s last works, subject to some correction and rearrangement after his death. It cannot have been retrospectively derived from Bukhari’s Sahih, as Calder thought, yet neither can it have been the basis of the Sahih, for it omits to mention fourteen percent of the men in the Sahih and mentions personal evaluations of only six percent of all its subjects. Its principal function seems to have been to identify traditionists by name. Inasmuch as it bespeaks sole reliance on isnad analysis to sort strong and weak reports, al-Tarikh al-kabir may represent a particular Khurasani tendency in hadith criticism. More certainly, it represents the professionalization of hadith science as against the amateurism evident behind Ahmad ibn Hanbal, al-Illal wa-ma rifat al-rijal.

To summarize, Bukhari’s Tarik was a later publication of Bukhari and doesn’t mention fourteen percent of the men in the Sahih and mentions personal evaluations of only six percent of all its subjects. This makes historians believe that his Tarik work was a completely separate work, such that not only was it not used as part of his evaluation process during his compilation of his Sahih, but it had no relation to his Sahih work.

In addition in another article by Christopher Melchert, The Theory and Practice of Hadith Criticism in the Mid-Ninth Century, he also states:

[I]t turns out that the massive biographical dictionary of the famous collector and critic al-Bukhārī (d. Khartang, near Samarqand, 256/870), al- Tārīkh al-Kabīr, almost never mentions anyone’s date of birth (none was found in a sample of 200), seldom anyone’s date of death (6 percent of the sample), and equally seldom evaluations of men’s trustworthiness (6 percent).4 Its evident purpose was to identify names in asānīd.

So the very thing one would expect from a biographical book appears to be lacking.

SUMMARY: CIRCULAR ARGUMENT

In summary, from what we can tell, Hadith compilers collected large volumes of Hadith and sourced them for their works without the use of any biographies. Then, later generations used the chain of narrators (isnad) from these Hadith to extrapolate who lived in what time period and supposedly met with whom and the Hadith’s content (matn) to determine the narrators’ trustworthiness for their reports. Afterward, they compiled these names into books with their findings. Now, today, people go to these biographies to confirm the births and deaths of these individuals and the trustworthiness of their reports, and surprise, surprise, it confirms the compiler’s findings.

As beautifully articulated by X user @BalaamAndDonkey,

“The reliability of a hadith hinges on the reliability of its narrators. But the reliability of the narrators hinges on the reliability of their hadith. It was always circular.”

Further Reading:

- This point is also mentioned in the following presentation, “Introduction to Hadith,” given by Dr. Joshua Little on the podcast Bottled Petrichor, starting around the 15-minute mark.

3 thoughts on “The Circular Logic of Hadith Biographies (Ilm al-Rijal)”